Sampson v. Tousey

This page contains notes on a series of lawsuits involving Sampson (alias Thomas Record), who accused William Record and Zerah Tousey of wrongfully enslaving him around 1812 in Indiana and Kentucky.

I’m still piecing together exactly what happened in this case, but here’s my best educated guess, based on the evidence currently available to me: probably William Record moved to Indiana with a slave named Sampson sometime before the War of 1812. (Of course, slavery was illegal in Indiana, but as salafia2013 and others have shown, this didn’t prevent white settlers from attempting to bring them there and continue to exploit them through long indentures or quasi-slavery.) Record then probably attempted to sell Sampson across the river to Zerah Tousey of the [Tousey Family], who was living in Boone County, around 1812. Based on court filings, Sampson appears to have then remained as a “slave or servant” of Tousey’s until January 1, 1830, at which point he sued in Dearborn County for $1,500 damages caused by wrongful enslavement.

Sampson (now alias “Thomas Record,” an interesting choice given that this was also William Record’s son’s name) was also married in 1830 and had already appeared, in 1829, as a taxpayer in Dearborn County, so the timeline is fuzzy here—he seems to have been recognized as a free man of color in Indiana (and in fact William Record appears at one point to have cited that fact as evidence that he should/could have sued earlier). At any rate, he won his case against Record in 1830 and a jury awarded him $83 in damages (much less than he had asked), but his case against Tousey was more protracted, partly because Tousey was a non-resident of Indiana. An effort to collect $1,000 in monetary damages from Tousey went all the way to the Indiana Supreme Court, where the final outcome is still unclear to me.

Parties

Sampson (alias Thomas) Record

On May 26, 1830, “two persons of color” named “Sampson alias Thomas Record” and Maria Smith were joined “in wedlock according to law” in Dearborn County, Indiana, by an officiant named N. B. Griffith. (See the marriage registration.) This is probably the “Thomas Record” listed in the 1830 census for Lawrenceburg, Dearborn County (household of all “free colored persons”: one under 10 male, one 36-55 male, one 25-36 female). Judging from the later proceedings in this suit, it seems likely he was owned at some point by William Record, though how he got his alias name—and why it is the same name as William Record’s son (see below)—is still unknown to me. He is named as “Sampson (a man of colour)” in a published listing of taxpayers in 1829.1

William Record

An early settler of Dearborn County, he arrived in 1807 and then settled on a farm in Sparta Township in 1816. He is listed in the 1820 census for Dearborn County with a household of 4 free white persons and 4 in the column “all other persons except Indians not taxed.”2

His son Thomas Record was born in 1810, and appears in the 1830 census for Langley Township, Dearborn County (household of all free whites: one 15-20-year male, one 70-80 male, one 5-10 female, and one 60-70 female). He was named in his father’s 1835 will (see Ancestry.com) and married in July 1832 to Hannah M. Sanders. They also appear in the censuses for 1850 (see Ancestry.com) and 1870. Thomas Record died in 1895 and is buried in Dearborn County, along with a son who died in the Civil War.

Zerah Tousey

One of the three brothers who settled in Boone County, Kentucky, around 1803. See Tousey Family. He died in 1831 or 1832, and his son Erastus Tousey also appeared in court concerning the case.

The Lawsuits

| Date | Action |

|---|---|

| 1812 | Sampson forcibly enslaved |

| 1829 Jan. 1 | End of Sampson’s detention by Tousey |

| 1829 Mar. 26 | Sampson files suit in Dearborn againt Wm. Record and Tousey |

| 1829 Apr. 7-9 | Wm. Record replies to suit; an arrest warrant issued for Tousey |

| 1829 May 21 | Sampson files suit against Tousey in Dearborn County; a writ of attachment issued |

| 1829 Oct. 5 | Tousey action continued to next term |

| 1829 Oct. 12 | Sampson replies to Wm. Record’s pleas |

| 1829 Oct. 15 | Wm. Record files rejoinder |

| 1830 Apr. 11 | Tousey action continued to next term |

| 1830 Oct. 11 | Court orders notice of attachment on Zerah Tousey’s property to be published in Western Statesman |

| 1830 Apr. 19 | Jury finds in favor of Sampson in suit against Wm. Record |

| 1831 Sept. 27 | Tousey moves to quash Sampson’s action because of irregularities in the writ of attachment |

| 1831 Oct. 17 | Court rules in Tousey’s favor to quash Sampson’s action; Sampson appeals |

| 1831 Oct. 25 | James Dill, Dearborn clerk, makes transcript of Tousey case for Supreme Court appeal |

| 1831 Nov. 11 | Tousey case heard before Supreme Court |

Sampson v. William Record and Zerah Tousey

In 1829, “Sampson, alias Thomas Record a man of colour” brought a suit in the Dearborn County (Indiana) Circuit Court against William Record and Zerah Tousey of the Tousey Family. It was an “action of Trespass assault & Battery and false imprisonment” claiming that Record and Tousey had wrongfully enslaved the plaintiff:

in the year of our lord 1812 at the county of Dearborn and within the jurisdiction of this court with force and arms made an assault upon him the said plaintiff and then and there beat and bruised and illy treated him the said plaintiff and then and there forcibly imprisoned him and forcibly and violently seized the said plaintiff and carried him into the state of Kentucky and kept and detained him there in prison without any reasonable or probable cause for a long time to wit for the space of fifteen years [perhaps the length of an indenture contract?] then next following and forcibly compelled the said plaintiff to work and labour for theirs the said defendants use and benefit for all the time afore said without any compensation whatever against the will and consent of him the said plaintiff contrary to law and against the peace and dignity of this state to the damage of the said plaintiff of fifteen hundred dollars and therefore he sues …3

On April 7, 1829, William Record’s attorneys appeared before the court moving that the plaintiff give bond with security before the cause is heard. On April 9, William Record also filed his separate plea “and defends the force and injury when &c and says he is not guilty of the said Trespasses assault battery and false imprisonment in manner and form …” and also stating that he had not done any of these things in the three years before Sampson filed his action (apparently an appeal to a statute of limitations). On the same day, Sampson appears to file his bond and the record notes that Tousey has not responded to a court order to appear, and so an “alias capias” (arrest warrant) is issued for Tousey and the case is continued to the next term.4

On October 12, 1829, the case resumed, and Sampson replied to William Record’s pleas by explaining that he could not have filed suit earlier:

he says that the said defendant at the time of the committing of the said trespasses in plaintiff’s declaration mentioned was a resident of the Territory of Indiana and hath ever since been until the commencement of this suit been a resident of the said Territory and State of Indiana and he further saith that on the said [blank] day of [blank] in the year 1812 in said Declaration mentioned the said defendant William Record at the place in the county of Dearborn aforesaid and within the Territory aforesaid and the said Zerah Tousey then and ever since a resident of the State of Kentucky so as aforesaid assaulted the plaintiff and him the plaintiff so as aforesaid forcibly and unlawfully seized and imprisoned and he the said William Record then and there forcibly and unlawfully sold and conveyed the plaintiff as a slave or servant to the said Zerah Tousey who then and there by the fraud collusion and with the aid of the said defendant William Record forcibly and unlawfully took and carried the plaintiff as a slave or servant into the state of Kentucky and him the plaintiff forcibly and unlawfully by the force covin & collusion of the defendant then kept and detained as a slave or servant until the first day of January in the year 1829 and so the plaintiff saith that the said assaulting and false imprisonment of the plaintiff by the defendant was one continued assaulting and imprisonment from the said [blank] day of [blank] in the year 1812 until the said first day of January 1829 …5

He adds that because he brought the suit within one year after the termination of this continued trespass, he has not violated any statute of limitations. Record files a rejoinder on October 15, 1829, that the plaintiff was “at large and at liberty in the state of Indiana” for a year before the suit and should have brought the suit then. This, Sampson denied, saying that:

the said defendant (with the said Zerah Tousey) has within three years next preceding the commencement of this suit forcibly and unlawfully and by force and collusion assaulted seized and detained the said plaintiff and held him in bondage nor was the said plaintiff during the time aforesaid and more than one year preceding the commencement of this suit at large and at liberty in the state of Indiana.“6

The court rules that the plaintiff can maintain his action against Record despite the latter’s rejoinders and “it is considered by the court now here that the said plaintiff do recover against the said William Record his damages by him by reason of the trespasses aforesaid sustained but because there is an issue of fact to be tried [i.e., whether Sampson was at liberty to file the suit sooner, and whether the trespass continued up to the period three years before the suit commenced],” the court delays final judgment until after a trial of fact, and the case is continued to next term.7

Finally, on April 19, 1830, a jury trial is held (the jurors are listed), and the jury “do say and find the defendant guilty and assess the plaintiffs damages at eighty three dollars.”8

The local papers took no notice of the decision. On the contrary, the Indiana Palladium stated on the 24th: “The circuit court of this county closed its session yesterday. During the term few civil cases of importance were tried.”9

Sampson vs. Zerah Tousey

In May 1829, Sampson filed a separate suit against Zerah Tousey, claiming he was owed $1,000 for “work and labour done and performed … for and in behalf of him the said Zerah Tousey, and at his special instance and request, which is now due and unpaid.” At the same time, the court sent an order to the sheriff of Dearborn County requesting that he attach any property owned by Tousey found in the county.

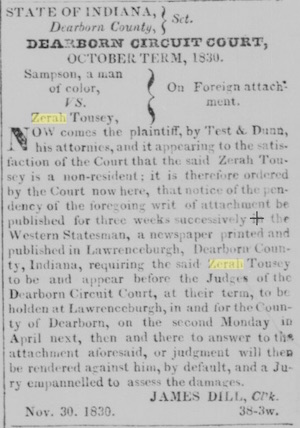

Excerpt from Lawrenceburg Western Statesman, December 10, 1830, p 3.

Later, in October 1830, the court ordered that notice of the writ of attachment against Tousey be published in the Western Statesman, together with a summons for Tousey to appear in court or have a ruling made against him by default. (The notice did appear as ordered: see, for example, Lawrenceburg Western Statesman, December 10, 1830, available on Hoosier State Chronicles.)

A subsequent filing, made in March 1831, disclosed that in May 1829 Tousey “undertook and faithfully promised the said Sampson to pay him for said last mentioned sum of money when he the said Tousey should be thereunto afterwards requested, but the said Tousey, though often requested so to do hath not yet paid the said money or any part thereof but wholly refuses to do so.”

In September 1831, however, Tousey’s attorney Amos Lane appeared before the court and moved to “quash the proceedings aforsaid for irregularities therein,” arguing in particular that the security bond filled out with Sampson’s original affidavit was not completed prior to the issuance of the writ of attachment. Sampson’s attorney’s, Test and Dunn, resisted the motion, but a few days later, the court upheld Lane’s motion and threw out the case.

The discovery of the irregular security bond was made by Amos Lane and Erastus Tousey on September 26, the first day of the session of the circuit court.

As in the case against Record, the newspapers took no notice of the trial. On the contrary, the Indiana Palladium of October 1, 1831, reported that “the circuit court commenced its session,” but “no civil cases of much importance have yet been tried.”10

Sampson’s attorneys filed an appeal to the Indiana Supreme Court, which took up the case. (Much of the above information comes from this case file available in the Indiana State Archives.) James Dill, the Dearborn Circuit Court clerk, then forwarded papers from the case to the Supreme Court, including the arguments of Amos Lane in favor of dismissal (primarily, “because the attachment issued without a bond being first filed as the law requires,” and Erastus Tousey, Zerah’s son, had witnessed the bond being filled out after the attachment had been issued) and the response of Sampson’s lawyers.

The Supreme Court’s order book indicates, however, that Sampson withdrew his appeal, probably on November 15, 1831, because of Zerah Tousey’s death:

At this time comes the plaintiff by his counsel & sugges[ts] the death of the defendant since the last continuance of this cause, & on his motion leave is given him to withdraw the record in this cause.11

According to the archivist, Michael Vetman, who looked at the order books for me, this is the last mention of the case on the order books.

Miscellaneous

- Reference to the case on Indiana Historical Society webpage, which also suggests that Sampson may have eventually gone (or tried to go) to Liberia.12

- The court order book for Dearborn County that served as a lead for the case

- On September 30, 1831, the Western Statesman reported that the circuit court was in session but did not mention this case, focusing on criminal ones. It also reported on “Another Insurrection” in North Carolina, suggesting that “the insurrection among the blacks in Virginia, recently noticed, was but the prelude to a more general and more alarming rising of the blacks farther South … which we shudder to contemplate.”13 An Indiana black code preventing any “black or mulatto person” from coming into Indiana without bond went into effect on September 1.14

- George Dunn and John Test, Sampson’s attorneys, were National Republicans and anti-Jackson men.15

Lawrenceburg Indiana Palladium, November 14, 1829, on Hoosier State Chronicles.↩

These four are likely black slaves or servants: since slavery was technically illegal in Indiana, census takers sometimes placed these people of indeterminate status here, according to salafia2013, p. 88.↩

Dearborn County Circuit Record (Complete), Book #3, p. 479, Dearborn County (Indiana) Courthouse.↩

Dearborn County Circuit Record (Complete), Book #3, p. 479-80, Dearborn County (Indiana) Courthouse.↩

Dearborn County Circuit Record (Complete), Book #3, p. 481, Dearborn County (Indiana) Courthouse.↩

Dearborn County Circuit Record (Complete), Book #3, p. 482, Dearborn County (Indiana) Courthouse.↩

Dearborn County Circuit Record (Complete), Book #3, p. 483, Dearborn County (Indiana) Courthouse.↩

Dearborn County Circuit Record (Complete), Book #3, p. 484, Dearborn County (Indiana) Courthouse.↩

Indiana Palladium, April 24, 1830, p. 3.↩

Indiana Palladium, October 1, 1831.↩

Indiana Supreme Court Order Book 3, p. 503, Indiana State Archives.↩

That page repeats information from Chris McHenry, “African Americans’ Contributions to the County,” Lawrenceburg Journal-Press, February 3, 2009, pp. 8-9: “There is a letter written to the Federal government on his [Thomas Record’s] behalf by Jesse Holman, asking them to help Record and his family to make the journey [to Liberia]. No actual record has ever been found to show that he really went, although he does disappear from the census about that time.” No citation or further information about the letter is supplied. (Janet McGill of the Dearborn County Historical Society provided me with the article.)↩

See “Convictions” and “Another Insurrection,” in Western Statesman, September 30, 1831, p. 3.↩

“A Law of Indiana,” Indiana Palladium, September 24, 1831, p. 1.↩

See “National Republican Meeting,” Western Statesman, September 30, 1831, p. 3.↩