A. J. Ward

Ward was part of the firm that received the very first lease of the Huntsville State Penitentiary, according to walker1988.

Walker mentions in a footnote that he suspects A. J. Ward was the same man who had been “the lessee of the Arkansas State Prison” in the early 1860s before fleeing Arkansas in 1863, “shortly before the arrival of Federal troops.” According to Walker, “the temptation is great to assume that the two men were one and the same even though no evidence to substantiate such a belief has been found” (30n).

Census records, however, provide some evidence that they were the same man. The 1860 census for Little Rock records an A. J. Ward who was a 25-year-old “Carriage Manufacturer” born in Connecticut and married to a 20-year-old Mary J. Ward, born in Tennessee. The 1870 census for Galveston then shows a 35-year-old “Commissioning Merchant” named Andrew J. Ward, married to a 31-year-old Mary J. There is a discrepancy: while Mary J.’s birthplace is listed in both censuses as Tennessee, Ward’s is listed as Connecticut in the first and Tennessee in the second. Still, this doesn’t seem enough to overturn the considerable other evidence that they were the same. If so, this could mean that Ward came to the state during the war.1

Early Life

Born in Connecticut, Ward also spent time in Memphis and arrived in Little Rock in 1857.2

In Arkansas

Leader of Mechanics Institute

My primary source of information about Ward’s Arkansas years is pierce2008. There, as Pierce shows, Ward was the leader of an 1858-1859 “campaign by the Mechanics’ Institute of Little Rock, a group of white workingmen, to rid the city of all types of unfree and degraded labor, including not only slaves who competed with whites but also convicts and free blacks.”3 This group articulated something like a “free labor ideology,” but the kind that produced enmity towards African Americans and the Union instead of sympathy.

The Mechanics’ Institute’s campaign on the eve of the war began back in the 1840s, when workingmen resisted the employment of convict laborers in Little Rock after a state penitentiary was built outside the city. White workingmen complained that “it was unfair that prisoners from all over the state and from all walks of life were transformed into Little Rock workingmen and complained that such training stigmatized mechanical and artisanal pursuits.”4 After the penitentiary twice burned down, a lengthy reconstruction delayed the reopening of inmate workshops until 1858, which sparked another round of protest calling for the expulsion of free blacks from the city and state and the confinement of slave labor to the soil. This time the protest was led by Ward, who now had a prosperous carriage making business in the city.

One centerpiece of the Institute’s new campaign was an opposition to free blacks that reveals the group’s—and presumably Ward’s—deep-seated racism. This part of their protest was also the most successful; the General Assembly passed eviction laws in 1859. The Institute also renewed workingmen’s opposition to the labor and training of “approximately 100 inmates at the Arkansas penitentiary.”5 The Institute called for the inmates to make only those products not already been produced in the city, and seem to have been successful. The governor agreed to limit inmate production to cotton goods, but the legislature had a different idea: leasing the penitentiary to a private individual who would solve the state’s financial problems with the penitentiary by paying the state and then using the inmates as laborers for his own profit.

Lessee of Penitentiary

The legislature thus began leasing the prison in early 1859, with the first lessee being Ward. This allowed Ward to achieve the workingmen’s goals from the inside, and in February 1860 he began “the shift of convict labor away from general manufacturing toward pursuits that did not compete with Little Rock’s workingmen.”6 At the beginning of his eight-year-lease, Ward built new workshops for cotton production.7

But Ward and his colleagues had a harder time winning support for their idea that slaves should be limited to agriculture and prevented from hiring themselves out (which, despite being illegal, seems to have been common by the late 1850s in the city). Some critics of Ward’s group accused them of being abolitionists, but the workingmen rejected the claim absolutely.

It was against that background that, in April 1861, Ward and other prominent mechanics “signed a resolution in support of secession and southern nationalism.”8 Ward then “transformed the penitentiary into the state’s most important producer of war materiel” until fleeing the approaching Union army, which liberated the state’s prisoners in September 1863; there’s no evidence of Ward or other workingmen “protesting this use of convict labor. Concerns over competition from unfree labor evidently yielded to the necessities of war.”9

Ward’s efforts to supply Arkansas military units also received a boost from the fact that “the penitentiary was utilized as a place of detention for deserters and war prisoners,” forty of which had already arrived by December 1861.10 By the beginning of 1862, Ward was producing a variety of items like the ones described in this advertisement transcribed from the Little Rock True Democrat by Vicki Betts:

[LITTLE ROCK] ARKANSAS TRUE DEMOCRAT, January 30, 1862, p. 2, c. 7

Shoes, Shoes.

Soldier’s Shoes, Negro Brogans, Gents’ High Quartered Shoes, Ladies’ Buskin Shoes, At the penitentiary Store, on Main street.

Jan. 30, 1862. A. J. Ward.

Production inside the walls also expanded to include smithing, coopering, and the manufacture of carriages, furniture, and various other military supplies. Unsurprisingly, given Ward’s background as a carriage maker, the “prison workshops were pivotal in supplying wagons and carriages used to transport goods to Confederate Arkansas soldiers.”11 The penitentiary also became a major supplier of uniforms.12

There are extensive records of Ward’s dealings with Confederate quartermasters in Arkansas on Fold3, indicating that Ward contracted with the Trans-Mississippi Department and Quartermaster W. H. Haynes to manufacture cloth and woolen goods in May 1863, with the stipulation that he move his works wherever so ordered by Kirby Smith, and with the provision that Ward could export cotton in order to buy needed machinery.

By the time Union troops arrived at the penitentiary on September 10, 1863, Ward had already fled.13

In Texas

After Ward fled from Arkansas in mid-1863, he appears to have gone first to Lamar County, and a captured “runaway slave” ad from Texas in 1864 indicates that Ward had brought slaves with them. One captured runaway named John “represents that he belongs to the State of Arkansas.” Another runaway ad suggests that Ward had started with a cotton train to Mexico around November (perhaps as part of an attempt to secure machinery for his contract work?) when at least one several slave who had been in the penitentiary ran away from him.14

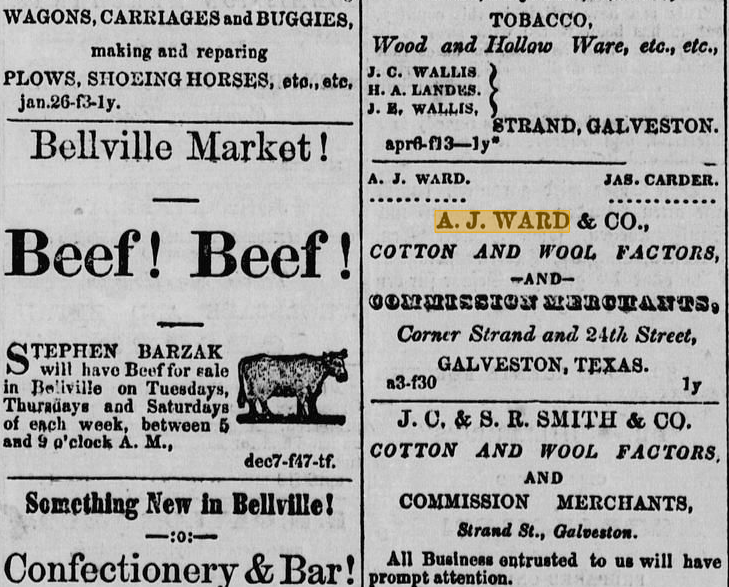

Ad from Galveston paper for Ward & Co.

It is possible, though I’m not yet sure, that Ward was one of the manufacturers who applied for the incorporation of the Bastrop Cotton and Wool Manufacturing Company in 1864. That would indicate his movement towards his ultimate decision to settle in Texas, if it was in fact him. Galveston ads in 1865 and 1867, as well as many other ads for this period, show him as a cotton and wool factor.15 The Bastrop company was later involved in a lawsuit over lands due to it under the incorporation of 1864. See also McCleary v. Dawson, and notice of the sale of the company in 1870.

In 1867, Ward is listed as a member of the Board of Directors for Merchants’ Mutual Insurance Company in Galveston. An article from Dec. 9, 1869 in The Houston Telegraph describes a devastating fire that destroyed the new Merchants’ Mutual Insurance Building. Though many buildings on the Strand suffered from the fire, the Telegraph estimated that the insurance company suffered the greatest amount of damage. The Telegraph lists A. J. Ward & Co. as an occupant of the Merchants’ Mutual Insurance Co. building and reported that the Ward & Co. office was a victim of the fire.

Prison Lessee

According to the Handbook of Texas entry on convict leasing, in 1871, A. J. Ward, E. C. Dewey, and Nathan Patton became the first lessees of the Huntsville State Penitentiary, after the state passed legislation implicitly admitting that it did not have the resources to maintain the prison. They won the contract primarily through the Republican Party connections of Patton, but Ward’s “large experience with the same duties in other states” was also mentioned as a reason for their selection.16 By that time, Ward had also become “the director of both the Port of Galveston and the Bolivar Point Wharf and Cotton Press Company,” as well as a director of the Texas Mutual Life Insurance Company.17 Shortly thereafter, Ward’s address changed to Huntsville in the Life Insurance Company’s ads.18

The terms of the lease, which began on April 29, 1871, according to walker1988, p. 30:

The act “authorized and required” the governor to lease the prison for a period of not less than ten or more than fifteen years. The lessees would have the right to direct the labor of the prisoners and could construct such additional buildings and alter existing structures in any manner they saw fit to keep the prisoners at profitable labor. They were given full use of all lands, buildings, machinery, tools, and other property belonging to the prison, with the stipulation that all property was to be kept in good repair.

The lessees were required to pay all costs “necessary for the support and maintenance of the penitentiary.” This would include all food, clothing, and medical care for the prisoners as well as the salaries of all guards and prison officials. They were further obligated to pay county sheriffs for costs incurred in transporting prisoners from the county of conviction to Huntsville. These payments were not to exceed $10,000 a year.

At the end of a convict’s sentence, Ward and Dewey were also required by the lease to give each convict $20 and a suit of cloths.19

According to a TSLAC exhibit, Ward, Dewey and Co. also paid the state $325,000 ($5.5 million in 2009 dollars).

Ward and Dewey took control of the prison on July 5, 1871. By 1872, the prison inmates had begun working to produce many of the same things that Ward had manufactured at the Arkansas prison: “furniture, doors, sash, blinds, wagons, boots, and shoes.”20 Around 638 worked in the prison walls, while 306 “worked on construction crews for the Houston and Texas Central Railroad and the Houston and Great Northern Railroad.”21

See also an 1873 advertisement for goods produced at the penitentiary.

A July 1873 article in the Houston Mercury said that Ward had organized a Fourth of July picnic/banquet for prisoners and described it in detail.^[“Our Huntsville Letter,” Houston Mercury, July 8, 1873, link.

At first, politicians hailed Ward and Dewey’s management. But complaints about prisoner abuse had begun to reach the governor’s office by the spring of 1872, including “charges that prisoners working in a railroad camp near Bremond had been brutally beaten by guards.”22

Ward responded to some of these charges in his speech to the National Prison Congress held at St. Louis. Ward excused the penitentiary’s divergence from contemporary penal reform programs on the grounds that:

in most respects, that plan and system would not apply in our case, or, in perhaps more correct terms, our material could not be made equal to the requirements of that higher standard. … In the older countries of Europe, as in the Atlantic states, the administrations of the different prisons have had an old criminal material to handle: criminals of intelligence; criminals crime-taught and crime-shrewd; criminals with desperate natures, and with hearts steeled against all influence for good. In the Texas state penitentiary we have, as yet, had but little of this element, this advanced criminal class, if we may be allowed the expression, the bulk of our convicts having been gathered from the ignorant masses …23

Ward also argued that the lessees’ focus on work stemmed not only from their having contracted the laborers from the state, but also out of their interest in the moral reformation of the convicts, who would learn to love labor as a result of their employment. And he claimed that punishment had been all but ended because of a system of rewards that gave convicts a personal stake in their labor.24 A legislative committee made up of three House members was sent to Huntsville in January 1874 and gave a similarly positive report about Ward and Dewey’s management of the prison, though the committee declined to look into the treatment of convicts laboring outside the walls “finding nothing to warrant mistrusting the lessee.”25

Exposure of Abuse

The realities of life inside the prison were much grimmer than Ward and the investigating committee let on, however, and that became clear later in 1874, when some army prisoners transferred from Huntsville to Kansas arrived in an emaciated state complaining of bad treatment in Texas. These prisoners pointed especially to the callous attitude of Ward:

One inmate told of Ward’s ordering a hospital attendant not to feed a sick prisoner. Another said that Ward instructed a prison guard to kill a particular inmate who recently had attempted to escape.26

Local and national newspapers, including the Galveston News, publicized these reports and challenged the official story line.27 A commission appointed by the governor to investigate the abuses produced a report in 1875 that confirmed many of these claims and underscored the horrific punishments endured in the Walls:

Even trivial offenses against prison regulations could result in a punitive ordeal so severe that gags had to be placed in the suffering prisoner’s mouth to stifle the screams. Guards often inflicted punishment at night so there would be no witnesses. Citizens living near some of the prison work camps stated that “the groans and entreaties of the convicts at night were often so absolutely heart rending as to prevent . . . sleeping.”28

Punishments included head-shaving and whipping; “a negro convict on the Patton plantation in Brazoria County had received 604 lashes by actual count on his naked back shortly before their visit.”29

Many of these findings seem to have referred primarily to conditions in the prison itself, because many others were scattered in isolated camps across the state. But this page and this book claims that an investigation done at the Lake Jackson Plantation, which Ward and Dewey purchased in 1873, showed abuses of convicts working there, including lack of medical attention, evidence of severe whippings, insufficient clothing, and more. This may be the same inspection conducted by J. K. P. Campbell, whose reports are part of a TSLAC exhibit on the penitentiary.

A physician’s report in July 1875 showed that conditions in labor camps were even worse than in the walls, especially at the Overton railroad camp, where 17 had to be returned to the prison walls because of scurvy (11), gun shot wounds (3), a mutilated arm (due to blows from captain of the guard), and self-mutilation (a man who had cut four fingers off his left hand to avoid work).30

Testimony from a convict collected in April 1875 revealed that “Col. Ward stocked a negro and struck him while there. I sam him punch a stick right in his eye and beat him with his stick when he was perfectly senseless. They can choke a man right down in these stocks in two minutes. … They threw water on the negro I referred to for two hours to bring him round. Veitch was the one who whipped him. He has stocked men in the factory—this was some time ago—until they were almost strangled to death.”31

Ward’s views on race revealed in his testimony in 1875 (p. 141) that the “dark cell” was used only to punish white men: “The dark cell would not be much punishment to negro. He would go to sleep and get fat, and the longer he stayed the better he would be pleased. With a white man it would be different.” He also declared that of the stocks, horse, and dark cell, he considered “the whip the most merciful mode of punishment that can be inflicted” (p. 147).32

His racialized differentiation of labor also came through:

There is a class of labor here that cannot be converted into skilled labor. Under our criminal laws, many men are sent for twelve months or two years, for misdemeanors. There is not time to make workmen of them before their time expires and yet they must be put to work at something. As for the negro he is a negro anyhow. If he is well controlled we can get work out of him outside and there will be but few escapes. Thus we endeavor to carry out the policy of the state which is that the convict shall [be] self-supporting and remunerative. This is as true of white men as of colored (p. 148).

And again on p. 161-2:

I am not satisfied with the penitentiary system. My idea is that the penitentiary system of a country should adapt itself to that country. What might be a good system in one locality might not be good in another. In Texas I believe that the system of manufacturing and agriculture should be followed. As far as possible white labor should be employed inside and black labor on farms. Where it is possible I think it a good thing to adapt men to useful trades. The objection frequently urged is that it brings convict labor into competition with free labor. The few thousand convicts in the world has very little effect upon the price of anything. The advantages to the community and to the convict in giving to the white man a trade places him above the necessity of a criminal act. … The argument of convict labor injuring free labor is really none at all, for the competition is really with the labor of other prisons, for Texas is today overrun with the productions of the prisons of other states, Sing Sing, Columbus, and the New England States. Where you have labor that can be utilized profitably it ought to be brought into operation and hence I cling to the idea of reformation I have always entertained and that is to make a criminal do hard work and pay his own expences, if not in the shops, on the public works, or in this state, for instance, to put him to labor more particularly on the farms. ….

And again on p. 163:

In regard to working convicts outside of the walls I have this to say. Since the war a change has taken place in this respect. The negro element is the preponderating one. Georgia with a fine architectual prison has not a convict on the inside of its walls. Louisiana that has appropriated recently within the last 4 years, $500,000 to buy looms, is working out all of her men on sugar plantations and elsewhere and are about building jetties for deepening their habor; and utilising them in these different ways. Mississippi works a body of men outside, principally on farms. Tennessee which never did work her convict labor outside the walls, until recently, is working two thirds of her prisoners in the iron mines, quarrying marble and on railways. Virginia, old Virginia–new Virginia has a penitentiary at Mountville—old Virginia, with her prison at Richmond, is working her men on coal fields, iron mines, and railway works. Joliet in Illinois, with magnificent shops is working one half their men on the outside their walls, in quarrying marble which is shipped to New York. Missouri has a convict prison that conforms to the modern idea which is now obtaining—namely, the Crofton system. This is a system wherein the prison is the smallest thing about it. It is just not large enough to hold them in their first stage of punishment.

The immediate reaction to the report was tepid, however. While a bill designed to “punish the employment of penitentiary convicts upon the works of private corporations” was introduced into the legislature, arguing that “the employment of persons convicted of crimes, brings such labor into competition with that of poor but honest laboring men” (the very argument Ward had made in Arkansas before the war), the committee reviewing the bill recommended against its passage on the grounds that it would be impossible to confine all convicts inside the walls, and that the lease system’s ability to bring revenue to the state made it unique among Southern penitentiaries. In its conclusion the committee also warned “the legislature that the lessees must have a free hand in their employment of the convicts.”33 The legislature instead elected to create a new penitentiary in Rusk.

End of the Lease

The political will to end the lease came more from the growing inability of Ward and Dewey to make timely payments on the lease. This had been a problem early on because expenses of prison renovation outstripped income from the subleasing or working of laborers. The financial situation was exacerbated by the Panic of 1873, which left lessees with “over a thousand prisoners who were without work but who, nevertheless, had to be fed and cared for.”34 By 1876, the state had decided to terminate the lease, though its final end was delayed until the new governor took office in 1877.35

A report by Campbell also found evidence that the lessees had “made absurd and extortionate charges for machinery and improvements at the penitentiary. … Four large boilers that had cost the state $6,000 had been disposed of, with one turning up in the sugar house of Ward, Dewey and Company at Lake Jackson, Texas.”36

The source for Walker’s information is gilmore1930. According to pierce2008, Ward spent time in Memphis before coming to Arkansas, so that could account for the discrepancy in his birthplace in the two censuses. Note that there is a Ward mentioned as owning a mill at Beaumont in 1863, but that is probably the A. J. Ward listed in Jefferson County in the 1860 census. There is also an Arkansas “A. J. Ward” listed in Van Buren in 1860, but this seems to be a different (but perhaps related) person. See also a Missouri tombstone for an A. J. Ward (potentially? married to Mary J.) born 1833 and died 1899.↩

pierce2008, 232.↩

pierce2008, 221.↩

pierce2008, 225.↩

pierce2008, 237.↩

derbes2011, p. 35.↩

pierce2008, 241.↩

pierce2008, 242.↩

derbes2011, p. 37.↩

derbes2011, p. 37.↩

See derbes2011, p. 38–46. The typical inmate at this time was a “single white male” between 20 and 40 years old. Only 11 black men were among the inmates in 1860.↩

zimmerman1949, 172.↩

See a better image of the first ad here.↩

This factory is mentioned in a letter from P. R. Smith to Pendleton Murrah, August 7, 1864, from the Mexico Border in Records of the Military Board of Texas, TSLAC, Box 2-10/301: “I have succeeded in getting (across this side of the Rio Grande) a considerable portion of my machinery. The Cotton factory is in rappid course of construction, at Bastrop, under the supervision of Judge Munger. Having sold to him and Mr. Ward an interest in the same. My wool carder, and cotton carder, will soon be at work near this place under the supervision of Maj. E. [Nance?] ( my partner). I have other machinery now in Matamoras, and I am desirous of introducing still other machinery.” He plans to travel to Manchester, England and asks Murrah for a leave of absence from military service that he can show to Kirby Smith. A subsequent letter dated September 17, in the same file, reveals that among the machinery imported were “a complete 768 spindle spinning factory” and a “double capacity” wool carder. He has also agreed to purchase, for the Bastrop Company, another large wool carder and “extra cotton machinery to make that factory, a 2100 spindle factory, instead of 768 spindles.”↩

Quoted in walker1988, 29.↩

walker1988, 29.↩

See, e.g., Galveston Daily News, January 12, 1872.↩

quoted in walker1988, p. 31.↩

walker1988, p. 32. Slightly different figures in crow1961, 96: “over five hundred convicts were assigned to the penitentiary at that time, with 300 additional convicts working outside the walls on farms, saw mills, and railroads.”↩

walker1988, 34.↩

E.C. Wines, ed., Transactions of the Third National Prison Reform Congress, Held at Saint Louis, Missouri, May 13-16, 1874 … (New York: National Prison Association, 1874), 235.↩

Ward did, however, seem to criticize, on. p. 239, the vast disparity between the severity of the crime and the severity of the sentence in Texas’s criminal code.↩

walker1988, p. 37.↩

See crow1961, 102, who notes a series of articles in the News published in March and April, 1875, titled “Horrors of the Texas State Penitentiary and Brutality of the Lessees.”↩

walker1988, p. 38.↩

W. A. Rawlings to the Penitentiary Board, July 1875, Records Relating to the Penitentiary, TSLAC, Box 022-9a.↩

Testimony of John Connor, April 1875, Records Relating to the Penitentiary, TSLAC, Box 022-11, Folder 4. This story corroborated by several other testimonies, by both employees and convicts.↩

Records Relating to the Penitentiary, TSLAC, Box 022-11, Folder 8a.↩

walker1988, 42. In 1873, the lessees received permission to delay payments due the state, in an act that was passed over the veto of the governor. See crow1961, 97-98.↩

According to walker1988, pp. 44-45, some of the rising dissatisfaction with the lease may have been politically motivated, since complaints about prisoner abuse had been made before Ward-Dewey and would be made after, without any action on the part of the state. It may be that the post-Reconstruction Democratic administrations cynically used the stories of prisoner abuse to punish a firm that had been awarded the lease due to Republican connections. The fact that a lease was quickly reissued to E. H. Cunningham makes this argument compelling, from Walker’s point of view. The delay in the actual termination of the lease may have been due to a request from Ward, Dewey & Co. that the lease be terminated after January 1 because of the dependence of planters on the labor of the convicts for the current season. See Ward, Dewey & Co. to Governor Richard Coke, June 8, 1876, Correspondence Concerning the Penitentiary, TSLAC, Box 022-2, Folder 8.↩