Huntsville State Penitentiary

The Texas State Penitentiary at Huntsville was created by legislation in March 1848 and accepted its first inmates in October 1849. During the 1850s, additional legislation created a prisoner-operated cotton and woolen mill to offset the costs of maintaining the institution.

Civil War Years

During the Civil War, the Huntsville penitentiary became a major center of cloth production for the Confederacy, as well as “Texas’s leading source of revenue.”1

By February 1863, Governor Francis Lubbock reported to the legislature that the penitentiary had “become a most important auxiliary to the government and is occupying a very prominent position in the public mind,” and that it was doign all it could to clothe both soldiers and indigent families. He also called for a “joint committee to examine into both the financial and mechanical workings of the institution,” composed of businessmen “not residing in the immediate vicinity of the penitentiary and strangers to its officers,” in order to address public rumors of mismanagement.2

The increased demand for textiles also caused some of the first labor shortages, as “the convict population declined from 211 to 157” between 1861 and 1863.3 Penitentiary officials sought to fill the shortage first by employing slave labor and succeeded in hiring about two dozen from prominent local citizens. News about this policy may have reached beyond Huntsville, too; in December 1864, William Pitt Ballinger sent “Dave,” an enslaved man who had stolen some of Ballinger’s things and then run away, to the Penitentiary “during the war” after capturing him.4 In their biennial report for 1863, the directors of the penitentiary also requested that the governor consider a law allowing them to hire slave labor, as well as a revision of the runaway slave law, so that the cotton manufacturing operation would not fall idle.5

Yet as perkinson2010 notes, “acquiring slaves for prison production … proved costly and challenging” due to high slave prices. Officials thus sought to capitalize on legislation that made runaway slaves who were had not been claimed by a legal owner within six months of advertisement by a county sheriff into the property of the penitentiary keeper, or that sentenced any person of color entering the state bearing arms for the Union to hard labor.6 Half a dozen men captured from on board the Harriet Lane during the second Battle of Galveston were transported to the prison.7 And a letter from Fort Towson, October 13, 1864, suggested that “slaves” who were captured in a recent Confederate raid at Cabin Creek in Indian territory (wearing “blue clothes” and carrying guns) should also be sent to the penitentiary for hard labor.8 These methods do not appear to have solved the labor shortage, however.

Penitentiary officials also attempted to remedy the shortage by accepting court-martialed Confederate prisoners into the Walls. In an 1864 letter to the governor explaining why military criminals were now being sent to the state penitentiary, the state’s financial agent at the penitentiary, S. B. Hendricks, noted that there have been labor shortages at the prison:

… the Penitentiary was short of labor, and it was difficult to procure it on any terms. Slave owners were averse to hiring us their slaves—the slaves already in our service were dissatisfied and some owners who had hired us slaves whose term of service was out refused to hire again. A good many convicts were being discharged,—but few new ones coming in and white labor, other than convict labor, could not be procured. You will readily see the strait into which the Sup’t was thrown. It seemed that our Factory operations would be arrested and thus a great pecuniary loss be inflicted upon the State.9

Although this practice was reversed by a local judge, a few military prisoners from Louisiana were received in 1865 after the Texas legislature authorized the practice.10

Postwar Years

In the immediate aftermath of the war, federal authorities ordered prison officials to release people who were imprisoned there for helping runaway slaves to escape. A letter dated June 30, 1865, from federal headquarters in Galveston and countersigned by A. J. Hamilton, ordered Thomas Carrothers, superintendent of the Penitentiary, to continue his duties but to immediately release “any persons in your charge who were imprisoned for the sole offense of assisting persons formerly slaves, to escape from masters” and to retain “any colored persons who, by reason of mental or physical infirmity may be unable to gain a livelihood elsewhere” until further orders were given.11

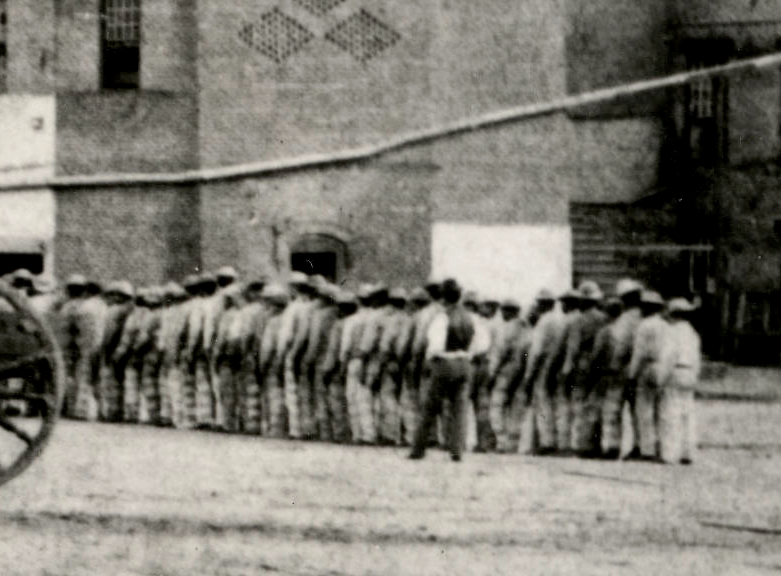

Close-up of Prison yard in Huntsville, circa 1873-1875, showing prisoners of color.

Almost immediately, however, the penitentiary began to receive an unprecedented number of new inmates, particularly in the form of freedpeople who were convicted under harsh Black Codes. The agent for the Penitentiary reported in November 1866 that “we have at this time 298 convicts; of that number only 98 are white men, 35 Mexicans, 155 Negro men, and 10 negro women. A large majority of the convicts are sent for theft. We are having almost daily acquisitions, most all of whom are negroes.”12 This represented a sharp departure from the antebellum years, when there were few prisoners of color, and raised questions about how house so many new inmates.

The legislature responded to the “overcrowding” problem on November 12, 1866 with a convict labor law that allowed for the leasing of “second class” convicts outside the walls of the prison under the supervision of the Board of Public Labor. The “first class” of convicts (who were incarcerated for capital crimes like murder) were primarily white, but “a larger number of ‘second-class’ convicts, most of them African Americans convicted of low-level offenses, were to be treated like impressed slaves during the war. They were to be deployed around the state on ‘works of public utility,’” defined broadly enough that it covered work for private corporations like railroads.13

By the mid-1870s, there were more convicts working outside the walls than inside.

Population

| Year | Walls | Outside | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 186014 | 182 | ||

| 186115 | 204 | ||

| 186216 | 211 | ||

| 186317 | 179 | ||

| 186518 | 165 | ||

| 186619 | ~143 | 250 | |

| 186720 | 411 | ||

| 186921 | 430 | ||

| 187222 | 638 | 306 | 944 |

| 187423 | 676 | 707 | 1383 |

| 187524 | ~1000 | ~1600 |

Freed People Committed

Box 022-10 of the Records Relating to the Penitentiary contains responses to a request from the governor to the penitentiary superintendent and county clerks to investigate the imprisonment of freed people. The people listed include:

| Name | County | Intake | Term | Crime |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dan Sanfley25 | Lamar | 1866 | 2 | theft |

| Andy Vining26 | Lamar | 1866 | 2 | theft |

| Red Haber | Lamar | 1865 | 5 | theft |

| James Patton | Lamar | 1865 | 5 | theft |

| Dick Hodge | Fort Bend | 1866 | 5 | |

| Moses Jackson | Houston | 1866 | 4 | theft |

| Scott Gibson | Colorado | [1866] | 2 | theft |

| Thomas Davis | Cherokee | [1867] | 2 | theft |

| Chester Williams | Travis | 4 | theft | |

| George Barnett | Anderson | 1866 | 2 | theft |

| Sam Butler | Anderson | 1866 | 2 | theft |

| Ran Kimbrough | Anderson | 1866 | 2 | theft |

| M. Hallums | Anderson | 1866 | 2 | theft |

| Jacob Falk | Anderson | 1866 | 2 | theft |

| Aaron Geary | Anderson | 1866 | 2 | theft |

| Warren Ormsby | Austin | 7 | burglary | |

| Isaac Foster | Austin | 1866 | 2 | theft |

| Cary Davis | Austin | 1865 | 5 | assault |

| Jack Dupree | Austin | 1866 | 10 | theft |

| Savis Blake | Austin | 1866 | 7 | murder |

| Jane Grisham | Brazos | 1866 | 2 | theft |

| Isaac Lloyd | Brazos | 1866 | 2 | stealing hogs |

| John Winston | Brazos | 1866 | 2 | stealing hogs |

| Daniel Ronwe | Bastrop | 1866 | 7 | theft |

| Henry Richardson | Bastrop | 1866 | 7 | assault to ravish |

| James Alexander | Bastrop | 1866 | 2 | theft |

| Henry Randolph | Bastrop | 1866 | 5 | theft |

| Dick Wilson | Bexar | 1867 | 2 | theft |

| Alfred Coward | Brazoria | 1866 | assault to kill | |

| Jack Green | Brazoria | 1866 | assault to kill | |

| Wash Brazos | Brazoria | 1866 | assault to kill | |

| Sam Watson | Brazoria | 1866 | murder | |

| George Spencer | Brazoria | 1866 | threats to kill |

Photographed the rest of the survey and uploaded to Omeka.27

Miscellaneous

Wartime legislation (see also following pages) passed by extra session of the Ninth Legislature, and by the Tenth legislature.

See Reconstruction Journal report.

The biennial reports are on microfilm at Fondren.

Letter from Thomas J. Calhoun, Clerk of the District Court of Houston County, dated December 2, 1867, to Governor E. M. Pease, details information about some convicts in the Penitentiary originally from his county:

Benjamin Jenkins was indicted for the offense of attempting to murder another freedman named Willis Rhodes, sentenced to 3 years in the State Penitentiary at the Fall Term 1866.

Joshua Freeman was convicted and sentenced at the Fall Term 1866, for the an [sic] assault with intent to kill upon one Simon Brown a freedman to 2 years in the State Penitentiary.

I will also call your excellency’s attention to the fact that another freedman was also convicted and sentenced to the Penitentiary for 4 years at the same term of the court, his name was Moses Jackson on the offence the theft of 20 dollars in specie and one pocket knife valued at one dollar.

These are all the cases that have been sent to the Penitentiary from the county since I have been clerk of the District Court.28

Another letter from D. C. Dickson, the penitentiary’s new financial agent, to Pease requests clemency on behalf of a freedwoman named “Mary” whom he believes had been wrongfully convicted of stealing in Gonzales County solely on account of “prejudice to her race.”29

See list of freedpeople in the Penitentiary from a February 26, 1867, Freedmen’s Bureau report.

Correspondence in 1869 suggests that J. J. Reynolds, the federal military commander of the Fifth Military District, was considering placing some convicts to work on the railroad.

In a letter from the Penitentiary Directors to the Richard Coke dated January 1875, the directors responded to Campbell’s inspection by complaining:

The impossibility of confining nearly 1600 prisoners inside the walls of the Penitentiary, which as your Excellency is aware was originally intended to hold 275 men, and cannot possibly hold more than 600, has compelled the Lessee’s, with the acquiescence of the Inspector and Directors, to provide for nearly 1000 prisoners in some other manner.

These convicts are scattered in detachments, varying from 10 to 150 men, over a large portion of Eastern and Southern Texas working on Rail-roads, farms &c. Each detachment is in charge of a Seargeant, who is selected by Messrs Ward, Dewey & Co. on account of their long services as guards, and with a view to their supposed fitness for such position. Occasionally however they are deceived, and a man totally unsuited to the position, because of his cruelty, or carelessness, is placed in charge, in consequence of which the convicts suffer.30

Quote from perkinson2010, 80. On wartime production, see especially derbes2011. There were some conflicts at the penitentiary itself caused by Confederate officers trying to get fabric for their own troops. See circular restricting the purchase of cotton cloth by Confederate officers issued in September 1863.↩

Message of Governor, February 5, 1863, House Journal of the Ninth Legislature, First Called Session, of the State of Texas, February 2, 1863-March 7, 1863, ed. James M. Day (Austin: Texas State Library, 1963), 12-16, link. In a speech that November at the regular session of the legislature, Lubbock reported on the findings of the committee that the Financial Agent had improperly used cotton purchased on his own account and for his own profit.↩

perkinson2010, 80.↩

See Records Relating to the Penitentiary, TSLAC, Box 022-4, Folder 15.↩

See lucko1999, 119. As Lucko notes on p. 120: “Institutional records fail to reveal the number of runaways incarcerated at Huntsville, but statements from Union prisoners of war, advertizements in the Texas Gazette, references to ‘runaway negroes’ in official records, and receipts for payments to individuals who captured escaped slaves reveal the presence of runaways at the penitentiary.”↩

See James A. Baker to Penitentiary Board, January 30, 1864, Records Relating to the Penitentiary, TSLAC, Box 022-1, Folder 6.↩

S. B. Maxey to W. R. Boggs, October 13, 1864, Records of the Governor Pendleton Murrah, Texas State Library and Archives Commission, Box 301-46, Folder 44. See also R. H. Thomas to S. B. Maxey, November 23, 1864, Records of the Governor Pendleton Murrah, Texas State Library and Archives Commission, Box 301-46, Folder 45; S. B. Maxey to Pendleton Murrah, December 9, 1864, Records of the Governor Pendleton Murrah, Texas State Library and Archives Commission, Box 301-46, Folder 46.↩

S. B. Hendricks to Pendleton Murrah, October 3, 1864, Records of the Governor Pendleton Murrah, Texas State Library and Archives Commission, Box 301-46, Folder 43.↩

See lucko1999, p. 123. In his January 1865 address to the Louisiana state legislature, Henry Allen recommended “that you enact a law authorizing the convicts to be sent to the Penitentiary of Texas for confinement and labor—the Legislature of that State having consented thereto.”↩

Correspondence Concerning the Penitentiary, TSLAC, Box 022-1, Folder 8.↩

Texas Almanac for 1867, 202.↩

Quote from [perkinson2010], 89.↩

Figures are for January 1 of each year. See walker1988. Also see crow1961, 85-86, which says that 209 entered penitentiary from 1861 to 1865, but an influx of 263 additional convicts entered in 1866. This may be the same over 200 that are discussed in butler1989. Slightly different figures given in derbes2011, p. 77, which cites 211 for 1860 (drawing on what appears to be an August 1861 report), and 118 in June 1865.↩

Letter from Thomas W. Markham, Penitentiary physician, to Col. John C. Easton, April 24, 1863, Correspondence Concerning the Penitentiary, TSLAC, Box 022-1, Folder 4. Giving figures as of the first of January each year. Markham also reported deaths of 7, 5, and 2 convicts in 1861, 1862, and 1863 (to date), respectively. Markham also reported deaths of 7, 5, and 2 convicts in 1861, 1862, and 1863 (to date), respectively.↩

Letter from Thomas W. Markham, Penitentiary physician, to Col. John C. Easton, April 24, 1863, Correspondence Concerning the Penitentiary, TSLAC, Box 022-1, Folder 4. Giving figures as of the first of January each year. Markham also reported deaths of 7, 5, and 2 convicts in 1861, 1862, and 1863 (to date), respectively. Markham also reported deaths of 7, 5, and 2 convicts in 1861, 1862, and 1863 (to date), respectively.↩

Letter from Thomas W. Markham, Penitentiary physician, to Col. John C. Easton, April 24, 1863, Correspondence Concerning the Penitentiary, TSLAC, Box 022-1, Folder 4. Giving figures as of the first of January each year. Markham also reported deaths of 7, 5, and 2 convicts in 1861, 1862, and 1863 (to date), respectively. Markham also reported deaths of 7, 5, and 2 convicts in 1861, 1862, and 1863 (to date), respectively.↩

Figures are for January 1 of each year. See walker1988. Also see crow1961, 85-86, which says that 209 entered penitentiary from 1861 to 1865, but an influx of 263 additional convicts entered in 1866. This may be the same over 200 that are discussed in butler1989. Slightly different figures given in derbes2011, p. 77, which cites 211 for 1860 (drawing on what appears to be an August 1861 report), and 118 in June 1865.↩

The out of walls figure is the number of convicts leased out to the Airline and Brazos Branch railroads, according to mancini1996. The in-the-walls figure are taken from the penitentiary superintendent’s report in November 1866 that “we have at this time 298 convicts; of that number only 98 are white men, 35 Mexicans, 155 Negro men, and 10 negro women. A large majority of the convicts are sent for theft. We are having almost daily acquisitions, most all of whom are negroes.”↩

Report of the Freedmen’s Bureau dated February 26, 1867, which ads that 225 of these were freed people.↩

Letter from T. C. Bell, Superintendent, to M. C. Hamilton, June 10, 1869, Correspondence Concerning the Penitentiary, TSLAC, Box 022-1, Folder 16.↩

See [walker1988, 32.] A slightly lower figure for those in the walls (“over five hundred”) is given in crow1961, 96.↩

Report of Governor Coke in 1874, as cited by crow1961, 99: “… there were 676 convicts confined within the walls of the prison, an average of 3 to the cell. … There were 707 employed outside the walls, 255 employed on the various railroads and the remainder engaged in cultivating plantations and making brick.” Coke also called for revisions to the law that would allow more to be worked outside the walls.↩

J. W. Bush, Thomas J. Goree, B. W. Walker, Directors of the Penitentiary, to Governor Richard Coke, January 1875, Correspondence Concerning the Penitentiary, TSLAC, Box 022-2, Folder 2. A report from May 31, 1875 by J. K. P. Campbell reports 530 inside the walls and 1172 outside, for a total of 1699 after allowing for deaths, discharges, escapes, and pardons. See Records Relating to the Penitentiary, TSLAC, Box 022-6, Folder 1. By August there were 1852. See Records Relating to the Penitentiary, TSLAC, Box 022-6, Folder 5.↩

Both Sanfley and Vining were sent to work on the Air Line RR and escaped from there, according to letter from T. C. Bell to Thad. McRae, Dceember 27, 1867, Records Relating to the Penitentiary, TSLAC, Box 022-10, Folder 7. The same letter mentioned two others, Robert Brooks and William Rusk, who could not be found on the books.↩

Both Sanfley and Vining were sent to work on the Air Line RR and escaped from there, according to letter from T. C. Bell to Thad. McRae, Dceember 27, 1867, Records Relating to the Penitentiary, TSLAC, Box 022-10, Folder 7. The same letter mentioned two others, Robert Brooks and William Rusk, who could not be found on the books.↩

Other names mentioned in my photos: Martin Moore, a woman named “Mary” who was recommended for clemency,↩

Correspondence Concerning the Penitentiary, TSLAC, Box 022-1, Folder 12.↩

Correspondence Concerning the Penitentiary, TSLAC, Box 022-1, Folder 12.↩

Correspondence Concerning the Penitentiary, TSLAC, Box 022-2, Folder 2.↩