Gerard Brandon

Descendants identify the man in this photograph, found on Ancestry.com, as Brandon.

Gerard Brandon (1818-1874) was the Mississippi planter who purchased Henrietta Wood and then took her to Robertson County, Texas, during the Civil War. The bulk of his papers are in several collections at Historic Natchez Foundation.

Genealogy

Brandon was the eldest son of the Mississippi Governor Gerard Chittocque Brandon (1788-1850) and Margaret Chambers. His brother was Dr. James C. Brandon (1820-1884), with whom he was particularly close; both brothers named sons after the other.

See Goodspeed’s entry on the Brandon family.

Brandon married Charlotte Smith Hoggatt in 1840 in Adams County, Mississippi. The couple had numerous children, though only five survived into adulthood; four daughters died of natural causes during the Civil War.

Vital statistics in the below list draw on the Brandon Children website and a public family tree on Ancestry.

- Philip A. Brandon (b. 1841, d. 1859 in the Princess steamboat explosion; see photo of tomb near Brandon Hall)

- Margaret Brandon (b. 1843, d. 1844; see photo of grave near Brandon Hall)

- Elizabeth Elmina C. “Ella” Brandon (b. 1844, d. 1900; married Aaron “Tip” Stanton on October 12, 1865)

- James C. “Jim” Brandon (b. 1845, d. 1909)

- Charlotte “Lottie” Brandon (b. 1847, d. 1885; married Joseph C. Pierce

- Gerard C. Brandon (b. 1849, d. 1854; see photo of tomb near Brandon Hall)

- Agnes Brandon (b. June 29, 1851, d. January 19, 1862; see photo of grave near Brandon Hall)

- Sarah Brandon (b. June 29, 1851, d. December 13, 1862; see photo of grave near Brandon Hall)

- Anna Brandon (b. 1853, d. 1854)

- Mary Brandon (b. 1855, d. 1931)

- Alice Brandon (b. 1856, d. 1862; see photo of gravestone near Brandon Hall)

- Geraldine Brandon (b. 1861, d. 1864)

- Charles Gerard Brandon (b. 1864/1865, d. 1935)1

Ella Brandon Stanton’s daughter, Charlotte Brandon (1866-1936), married Dunbar Surget Merrill. Their son Dunbar Merrill had a daughter named (Ruth Britton) Dunbar Merrill Flinn (1926-2006), whose attic contained many Brandon family papers before they were donated to the Historic Natchez Foundation.2

Some pictures of the Brandon cemetery are on Flickr.

Antebellum Period

With numerous slaves and landholdings in Mississippi and Louisiana, Brandon was one of the wealthiest planters in Natchez when the Civil War began. See Goodspeed’s Biographical and Historical Memoirs of Mississippi, vol. II, p. 817, which claimed that at the beginning of the Civil War, Brandon owned a million dollars worth of slaves.

According to scarborough2003, p. 432, Brandon owned 706 enslaved people on plantations in Adams County (512), Concordia Parish (113) and Tensas Parish (81) in the 1860 Census, making him the tenth largest slaveholder in Scarborough’s sample for 1860, even though he does not appear on Scarborough’s sample of planters with over 500 slaves in 1850.

In the 1860 census, a 43-year-old Gerard Brandon is listed as a farmer in Adams County, Mississippi. The value of his real estate was $170,000 and his personal estate was $400,000. His overseers are John Lyle (born in Kentucky) and William Hurley (born in Scotland, accompanied by his wife Rose). His wife Charlotte (39) and children Elmina (16), James (14), Charlotte (12), Sarah (9), Agnes (9), Mary (5), and Alice (4) are listed a fellow members of the household.

In the 1870 census, a 52-year-old Gerard Brandon is listed as a planter in Adams County, Mississippi. The value of his real estate was $18,000. His wife Charlotte (age 49) and his children Mary (15) and Charles (5) are listed as fellow members of the household.

Brandon Hall in Natchez, MS was built by Gerard Brandon and his wife Charlotte (Hoggatt). Construction on the home began in 1853 and it was completed in 1856.3

Slave schedules for the 1860 Census confirm Brandon’s large slaveholdings. These searches were performed by Christina via HeritageQuest as part of her RA Assignments.4

- Adams County, Mississippi: 154 enslaved people are listed under Gerard Brandon. 33 slave dwellings were also noted. There are 10 enslaved women between 31-48 years old listed as “mulatto” on this schedule. (pg 44a-44b)

- Adams County, Mississippi: 217 enslaved people were listed under Gerard Brandon, “trustee for children.” 70 slave dwellings were also noted. (pg 45a-46a)

- Adams County, Mississippi: 93 enslaved people were listed under Gerard Brandon, “trustee for wife and children.” (pg 46a-46b)

- Concordia Parish, Louisiana: 113 enslaved people are listed under G. Brandon of Canebrake (the Canebrake Plantation in Concordia previously owned by James Green Carson). (pg 72a-72b) See menn1964 and weaver1945.

- Tensas Parish, Louisiana: 81 enslaved people are listed under Gerard Brandon of Monclova. See menn1964.

An 1858 runaway slave ad for “Elijah,” who said Gerard Brandon was his owner, is in the Runaway Slaves in Mississippi project, edited by Douglas Chambers and Max Grivno, on p. 536.

Civil War

Brandon’s family was one of the staunchest supporters of the Confederacy in the area. See scarborough2003, p. 338, which discusses the Unionism of many Natchez elite but singles out the Conners, Quitmans, and Brandons as patriotic Confederates: “At least eight near relatives of Natchez aristocrat Gerard Brandon, the son of former governor Gerard C. Brandon,” served in the military. Two of Brandon’s brothers were killed in battle, one at Chancellorsville and one at Fredricksburg (p. 329).

Refugee in Texas

Brandon was one of many Refugees to Texas who took Refugeed Slaves there to escape emancipating Union armies.

Texas Diary

Brandon kept a diary of his Texas sojourn which is probably held today by a family descendant. A typed transcription made by Helen Rayne in 1999 (with parenthetical comments by Rayne throughout) was donated to the Dolph Briscoe Center by the Historic Natchez Foundation in 2001. The Foundation also has a photocopy of the original, which includes some pages not in the transcription and also reveals a number of errors in the typescript.

Brandon mentions his diary in a letter to his daughter Ella, dated October 21, 1863, and found in the Vonkersburg Family Collection at the Historic Natchez Foundation. He says he has “made some rough notes of incidents” to share with her and intended to send them with “Jim” (his son) “but cannot well do without the book.”

Route to Texas

Based on his diary of the trip, Brandon left in early summer 1863. An affidavit provided by Brandon in a later lawsuit indicates he departed on July 1.5

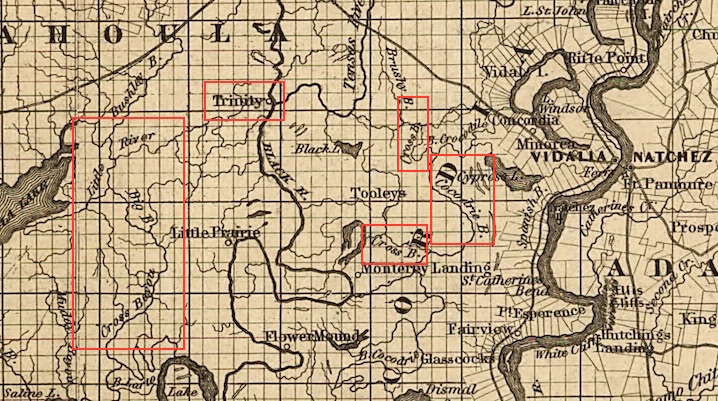

Clipping of J. H. Colton’s map of the state of Louisiana and eastern part of Texas (1863) showing locations mentioned in Brandon’s account of his flight from Natchez.

Notations on page 5 of his pocketbook indicate that on July 1, he first paid $140 for a ferry at Quitman’s (a reference to a contemporary place in Adams County known as Quitman’s Landing and referred to in papers and military records of that time; it was north of Natchez). A second ferry location is illegible, but he also paid for ferries across Cocodrie Bayou and Cross Bayou. By the “3rd” he paid $53 for a ferry at Trinity, Louisiana (likely to cross the Black River), and then paid $38 to cross Little River on the 7th. His next ferry payment was to cross the Red River on July 11, likely on his way out of Alexandria.

He then traveled on to Texas via these stops, according to a list on an unnumbered page of his journal:

- Alexandria, Louisiana

- Sabinetown, Texas (possibly by July 14, when he paid $48 to ferry across Sabine River, according to page 5 of the journal)

- San Augustine, Texas

- Crockett, Texas

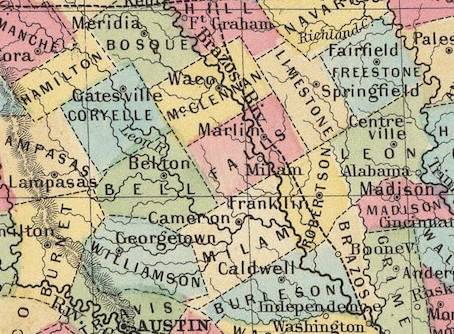

- Centreville, Texas

- Trinity River (specific place illegible, but may be Madisonville) (possibly by July 22, when he paid $28 for a ferry, according to page 5 of the journal)

If he followed marked roads out of Alexandria to the Sabine River, then he would have gone through Natchitoches, but that road would have taken him to Milam, Texas, not Sabinetown. Going directly from Alexandria to Sabinetown suggests that he crossed the swampy region between those places directly, avoiding the roads.

If he followed the road from San Augustine to Crockett pictured on Texas Map (1865), then he likely passed through Nacogdoches as well. (That route is supported by a notation on page 5 of his journal showing that he paid a toll at Neches on July 21.)

In November 2015, I retraced some of this route by car when coming back from Natchez.

Headed back to TX today using same route Brandon took with slaves, including Wood, in 1863. #ResearchRoadTrip pic.twitter.com/7lk820jLbt

— Caleb McDaniel (@wcaleb) November 19, 2015

Robertson County

After Brandon pursued several possible places to rent in Texas, Joseph S. Able, a resident of Robertson County, offered Brandon a place on his land “with 300 acres in cultivation 2 cabins & corn on the ground” as well as use of a mill. He would charge “$5 an acre for cleared land & let me pay for it by picking cotton at $1 per 100 pounds.” For more on Able, see Able Family.

“Gerod Brandon” appears on the 1864 County Tax Rolls for Robertson County with no real estate, but 270 slaves valued at $108,000, as well as $5000 in Confederate Notes and $6,125 in horses, cattle, and other property. In the same tax rolls is a “J. S. Able” who owns 3500 acres on the John Welch and Joseph Welch grants.6

This confirms that Brandon settled most of the enslaved people he brought to Texas in the northwestern corner of Robertson County, somewhere between Hammond and the Brazos River.7

Incidents in Texas

Note: Unless otherwise noted, page numbers below refer to my numbering of the photocopy pages of the full Brandon diary I acquired at HNF, not to Brandon’s numbering or to the Helen Rayne transcription. When possible, I have also noted the dates of Brandon’s entries.

p. 3: “Deaths on Trip to Texas,” continued onto 4. On the page opposite the list of deaths, there are also notations about “Middleton’s” expenses.

p. 4: Some more deaths; notes about wagon loads, presumably of cotton bales; ferriage and tolls on the route to Texas

pp. 5-11: a debit and credit ledger for the trip; debits begin on 5 (numbered by Brandon as 7) and then are carried over on 8 through 11, with a final total (summed by me from Brandon’s subtotals) of $19,145.60 in expenses by February 2; credits begin page 6 (numbered by Brandon as 8) and then continue on 13 to 14, where a final total made by Brandon on February 2 shows $10,168.25 in credits

p. 15:

Begin August 1863 entry. Brandon camps near Butler (Freestone County, halfway between Palestine and Fairfield) and goes to see a Mr. Morgan, apparently an acquaintance from Mississippi, who had brought slaves belonging to W. S. (or S. W.?) Sanderson to Texas.8 While at Morgan’s, he is introduced to Oliver Carter near Fairfield, who put him in touch with a Mr. Deming, who had a too-small place for sale, and not until January 7. Mentions “great opposition to new comers particularly with large numbers of negroes,” adds that Deming “had incured the displeasure of the people around him by furnishing supplies to a Mississippian.” Returns to find “Dud, jack S, Mose, Dicey’s & Lucy’s babys quite sick”

p. 16:

Difficulty of keeping enslaved people well because “they will eat imprudently & in evry way keep themselves sick. Dudley I think will die.” Arrival of Mrs Spark and her son, other Mississippi refugees, who had found and brought Jack Lancaster. Discovered that several men (Isaac, [Matt] & Charley) “had been in the hog business, cost me $30” (noted in ledger on p. 9, Brandon’s page 14); medicine scarce; “Oh! how Texas has been over stated”

p. 17:

Land he sees “will do fine for small Farmers of from 1 to 20 hands to make a living on, but to plant extensively or make a fortune I should never come here except on the creeks.” Hasn’t seen good hogs. Living “very poor.” His “travels for land” continue. Has dinner with a woman who is “hard on all who were not in the army,” two soldiers from Vicksburg also critical of Mississippians.

Some counties mentioned in Brandon’s diary, cropped from Texas County Map (1860)

p. 18:

Vicksburg veterans continue their critiques of planters who “stay at home to take care of our negroes.” They “hoped to hear of evry planter there losing everything they had, for they had done but little to deserve success.”

p. 19:

More critical talk from his dinner partners about rich planters, whose “negroes are dressed better than Texas soldiers.” Brandon feels it unfair but holds his peace. Begins August 3 entry at came near Dr. Milner’s Spring. Wagons and wheels being fixed. Milnor worried about his stock (thieves?), so Poole (overseer) left, presumably with slaves.

p. 20-21:

Narrative of a trip to a miller’s house.

p. 22:

“On my way to camp I called to see Mr. Blackshear, in Springfield,” who gives him “a very good dinner, pure coffee.” Begins August 9 entry: “This Holy Sabbath morn finds me near the banks of the Brazos, without meal or meat,” because of price gouging and worthless Confederate paper. “It almost makes me sick. I suffer much mentally.”

p. 23:

Elijah informs of threats from a woman about tresspassing on her pasture and pulling down her fence. Brooding about home. Mandy’s child died.

p. 24:

More on Mandy’s child. Begins August 11 entry. Conversation with Dr. Killibrou (?) about opposition to refugees, “particularly if they had much property,” and the slogan “rich man’s war & the poor man’s fight.” Another refugee who had fenced up a spring.

p. 25:

One half illegible. The other refers to Sandy’s desire, like his, to hear from home. This page also contains the line: “Henrietta conducts herself well,” as did some other enslaved people mentioned by name.9 But Brandon says “I am really tired, sick of them and being with them, a perfect dogs’ life, & will disgust anyone with the …”

p. 26:

“… whole race. My children must thank me for the attempt to save [?] this property for them for I have seen sights of trouble more than I can ever describe or make them sensible of.” Begins August 13 entry. Starts with Sandy for Col. Robertson at Salado (see Elijah Robertson). Describes the Brazos (he appears to spell as “Brassos”) as a “little, crooked, muddy [?]” stream.

p. 27:

Robertson offers him use of land, offers to put the deal in writing in Belton.

p. 28:

Tours Robertson’s college, then under construction.

p. 29:

Buttermilk at Robertson’s. Travels to Belton in buggy. Cobbler and corn bread with another host. Meat at “Bulls” “but so hard & dry no one could eat it.” Meats Esquire Jones, an opponent of secession who fears the postwar.

p. 30:

Eats water melons at Jones’s, drinks a mint julep, has dinner with “good soup & a peach cobbler.” “On Monday” (August 17?) he goes to look at Robertson’s land and is piloted by “Mr. Able.” He strikes new deal with Able to settle on his land: “he could let me heave as much land as Col. R. had offered, with 300 acres in cultivation, 2 cabins, & corn in the ground at $1 per barrel, and let me have the use of a mill …”

p. 31:

“… would charge $5 an acre for the cleared land & let me pay for it by picking cotton at $1 per 100 pounds.” Brandon agrees. Begin August 20 entry. Sends Sandy to post office hoping to hear from home. Returns from Salado to reports of death, including “Henrietta has just come to say Dicey’s little boy is dead.” After moving to Able’s, “All at Home for the war.” Description of the Able Family …

p. 32:

…and another Mississippi refugee named Williams.10 Difficulty getting a beef he had paid for. Cornelia’s screw worms …

p. 33:

… “such as kill thousands of stock in Texas annually.” Poole has been ill for three days. Expressions of homesickness. Begins August 24 entry: “no beef as yet now for four days.” Slaves “dissatisfied.” Reflections on number of slaves he has brought: “I am now content & feel if I can take care of what I have, I shall do very well.”

p. 34:

Doesn’t like to hire out, “& to feed them in idleness, they will soon ‘eat their heads off.’” Learns of a meeting of locals for resolutions on refugees and the “some 1000 or 1500 negroes moved into the region.” Someone offers to speak up in Brandon’s defense, “as mine looked ‘clean & orderly.’” Williams has sent “a ham, bucket of butter, & three water mellons.” Begins August 29 entry: demands from “persons wanting to hire negroes.”

p. 35:

“The whole country bleeds and is in mourning. I really sometimes wish the war was ended, & would rejoice to hear the glad tidings of peace.” Begins August 30 entry awakened by “a fuss about eggs & a chicken” and a slave who has “robbed a hen house of a neighbor last night.” Learned of others who “had been to a poor man’s house to beg bread & meat,” another robbery of rye “to make coffee.” Brandon vexed, curses.

p. 36:

He feels they are ungrateful even though he has done all he could to “make them comfortable, I won’t say satisfied.” Wishes Poole “had them on a place where had full work for them, could make them feel tired at night, & where others observed discipline, he might get along very well.” His enslaved people have a wide freedom of movement at night, in a land “where most of the people have no slaves, & have never been used to them, & where many say they want one for ‘company.’” He fears how Poole will get along “when I am gone.” He will leave “strict laws.” Begins September 6 entry, awakened again at night by “the cry of dogs & the yelling of men.”

p. 37:

Able reports a runaway, disputes over stolen money and trading done by Bill. “I whippped him a little.” Anthony has the money. Learns that some have been plotting to start off for Miss. A crowd of locals “very much excited” about the news and “declared that the negroes …”

p. 38:

“… must be sold out of this section, or hung, or I must move, as my negroes might be the cause of all the negroes being dissatisfied and many a man might loose his property by my coming here. Now I was in trouble.” The story told by Bill deepens in complexity, and involves a plot by Able’s son to run to Mexico, though most of his slaves deny that they were going to go along. Brandon strictly instructs them not to trade with anyone.

p. 39:

In view of all this he is satisfied he brought as many slaves as he “ought to have done, (for sometimes I have regreted [sic] I did not bring more) for after hiring out a good lot I have now more than I can find work for & am feeding on an expense which will in one or two years (if the war continues that long, but I sometimes wish it was over now) will make them cost very high.” He goes down the “Brassos” on Thursday “to get corn,” sees “some fine plantations, the people look more like home folks, but Texas shows out, viz. not the care, pains & comfort in fixing up places.” He couldn’t find corn. Goes Friday to see “after some negroes I had hired in Falls Co.” Stays with H. L. Bennett.

p. 40:

Discusses leaving Poole with a power of attorney, and one with Bennett if Poole becomes indisposed. Arranges situation for Phoebe.11 Feels gloomy, homesick.

p. 41:

Thinks about people at home. Discouraged by possibility of his being taken a prisoner when he tries to return.

p. 42:

List of troubles: “screw worms—how many of them there are. How many [illegible] I have doctored & sick negroes, swelled feet & legs, swelled stomachs, dyptheria, fever, seems to me nearly all man is heir to, but all well this morning & I am thankful it is no worse.” Medicine nearly out.

p. 43:

Begins September 15 entry. Arrival of Jim and Middleton, and “Sanford was behind with 58 negroes & some stock.” Jim and Brandon go to see Oliver Carter “to try and rent his place on the Brassos.” No rental, but he gets corn.

p. 44:

Stayed at a house in which “the Ladies (3) of the house washed their feet (in our presence) in the common wash pan. When he returned to camp,”Sanford had come up with all the negroes. … So I find my negroes out of doors, & stock poor, corn high & some difficulty to get it, & separated from my family." Report of a “Mrs. Sanderson” hung back in Natchez. “Enough to make a man gloomy.” Reads Ella’s letter. Begins September 28 entry.

p. 45:

Brandon and Middleton travelling. Eats well on the road. Horse foundered, took him to Middleton’s camp. Visits another refugee family, hears “some incidents they had heard of the occupation of Natchez.” Legal trouble with Hughes.12 Talks to lawyer “A. H. Weir of Centerville,” who “hit me a dig.”

p. 46:

Begins September 29 entry. Severe rain and wind. “The mill is out of fix, & too bad to get up a beef and all hands are on short rations.” Thoughts of home.

p. 47:

Begins October 3 entry. Friends visit from Waco. One is “hiring negroes to go 300 miles west for the government.” Brandon sends 40. Begins October 21, the “most melancholly day I have had in Texas.” James (Jim) leaves for home “& from thence to the army.”

p. 48:

Begins October 25 entry. Chilly weather. Begins November 2 & 3 entry, attends a public sale of someone’s effects. “Poole gone to the field.” Homesick thoughts, trying to read his Bible. Begins November 10 entry. Went to pay for some corn. …

p. 49:

“… had a good dinner & supper, spent a pleasant evening.” “Asthma & cramp colic.” Begins November 13th & 14th" entry, discusses hunting for deer. On November 15** went ot hear a “Mr. Wipple preach.” He was sent a bottle of wine, jelly cake, & pies. Sanford has gone to Monroe, returned about the 1st, and “the authorities say I have not had any negroes in their hands.” Hears that “the Yankees had not molested anyone in our neighborhood, & all were getting on pretty well.” Sanford “saw a family wash their feet in the skillet in which they had cooked their supper! they are the dirtiest people I ever saw or heard of & come nigher living out doors than any others.”

p. 50:

Begins November 27 entry. Cold front. A Natchez refugee visits and “told of many negroes who went to Yankees, that Billy Sanderson had killed himself drinking with them, that Fred’s wife had been hung, that Merrill was giving them dinner parties &c. but had heard never a word of my family.” Feelings of worry and suspense. Begins December 24 entry. Goes hunting for deer. Celebrates Christmas with Graves and “Dr. Mitchell.”

p. 51:

Begins December 26 entry, very rainy. Misses a dinner invitation from Graves. Begins December 27 entry. “Sanford Poole & Sandy had gone to kill a deer.” Middleton arrives, and he gets a package from home.

p. 52:

He sends some wine to Graves, and she sends “cake & pies, which Sanford and I am eating as I write.” Begins December 30 entry, hunting deer. Snowfall, “the deepest I ever saw in the South.” Begins December 31 entry, “bitter cold,” water freezes on the shelf inside his cabin. Reflects on James in the field. Unsure of his next steps, whether to visit home “and be on the dodge all the time, the great fear I have is being sent to a northern prison.”

p. 53:

“Left for home 4th Feby 1864.” On Sunday “attended church in forenoon, saw a fistfight in eve, & a company pass having in charge nine deserters. At San Agustine by 11th. Harrisonburg by the 16th, but”could not pass the pickets" and found “that all the Ferries on Ouachita & Tensas were destroyed or strictly guarded.” Backtracks to Alexandria.

p. 54:

Gets a pass in Alexandria. Asthma.

p. 55-56:

Lists his route, expenses, and ferriage for the trip back home. He came “407 miles.”

Postbellum Period

The Robertson County Tax Rolls for 1865 show “G. Brandon” owning 287 “horses, cattle, sheep & miscellaneous property,” valued at $2120, and no real estate.

The Robertson County Tax Rolls for 1866 show him with 25 horses and no real estate.

In June 1866, The New Orleans Daily Crescent published an announcement that Gerard Brandon’s wife Charlotte was awarded a separation of property between her and her husband by the Court of New Orleans. Brandon was also required to pay his wife $127,436 with legal interest and costs of suit.

Miscellaneous

- An 1898 essay by Gerard Brandon, Esq., presumably James C. Brandon’s son, on “Historic Adams County,” described as the “promised land” and the “cradle” of the state. It also recalled the antebellum slaveholders as “veritable lords of the manor, surrounded by all the luxury and refinement which wealth and slavery could produce” (p. 216), mentioning Brandon Hall in particular. The same descendant was apparently a Natchez lawyer who commented on the unequal application of criminal justice, particularly towards black Southerners in the nadir period. “Now I am not a special pleader nor an apologist for the negro,” he wrote in 1911, “but I am a most earnest advocate for an even handed justice, for an equal application of the law to all men who are subject to the law, be they Caucasian or African …”

- Winthrop D. Jordan. Tumult and Silence at Second Creek: An Inquiry into a Civil War Slave Conspiracy (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1995). Jordan investigates a slave conspiracy in 1861 in Adams County, Mississippi. Jordan states that Harvey Mosby, who testified about the conspiracy, mentioned “Elisha, who probably belonged to Gerard Brandon, a planter who controlled the largest number of slaves in Adams County. Very possibly Elisha was the same ‘Brandon’s teamster’ Orange told Alfred he had talked with. Obviously, the teamsters had considerably more mobility than most slaves; Brandon Hall was located some fifteen miles away, in the northern part of the county.” (no page number on ebook via Google Books)

- In Fall 2014 RA Assignments, Christina searched for “Gerard Brandon” in Chronicling America and America’s Historical Newspapers (which turned up only the below account of his lawsuit with his wife, and a suit from 1872 against Hughes, mentioned in footnotes to this page.) There were no viable results for “Girard Brandon” in the Chronicling America database or America’s Historical Newspapers database. The only references to “Gerard” or “Girard Brandon” in the Portal to Texas History database are reprinted articles concerning the Henrietta Wood case. There were no viable results for either spelling of Brandon’s name (outside of recirculated articles pertaining to the Wood case) in the American Civil War: Letters and Diaries, Documenting the American South, North American Women’s Letters and Diaries, American Periodical Series, University of Southern Mississippi Digital Collections, University of Mississippi Digital Collections, or Mississippi State Digital Collections databases.

To-Do List

- qq Transcribe relevant portions of Texas diary

- qq Go through probate records on Ancestry

Ancestry places birth on December 5, 1864.↩

See also this genealogy page and the Gerard Brandon children website.↩

See Steven Brooke, The Majesty of Natchez (Gretna, La.: Pelican Publishing Company, Inc., 2007), 92. Also “Brandon Hall” in Reid Smith and John Owens, The Majesty of Natchez (Montgomery, Ala.: Paddle Wheel Publications, 1969): “it is obvious that he, like so many of his contemporaries, had succumbed to the Greek Revival era of elegance. … Inside, behind the handsomely recessed main entrance, were parlor rugs from the Orient, services of English silver, mantels of the finest Italian marble and great pier mirrors from France.”↩

Since the 1860 slave schedule was not searchable at the time, the page numbers are provided for the Mississippi and Louisiana slave schedules.↩

The affidavit says that “on the 1st of July, 1863, the pending war, and the exigencies of the times compelled his hasty departure from this state for the state of Texas, where he was detained until February 1864. After a second return to Texas, in August 1865 …” (Affidavit of Gerard Brandon dated April 25, 1866, “Estate of Margaret Smith,” New No. 163, Probate Court, Adams County, Miss.) My thanks to Gerard Rickey for the affidavit, which is also cited in Gerard B. Rickey and Alan C. Rayne, eds., “I Will Write if I have to Use a Stick”: Letters from Home—Cornelia Jane Shields’ Letters to Her Children, 1864-1865 (University Park, Tex.: Estate of Sara Brandon Rickey, 2000), 63n6.↩

Thanks to Will Jones for locating Brandon’s name in the county tax rolls as part of his RA Assignments for Fall 2015.↩

See Map of Robertson County, Portal to Texas History.↩

Sanderson’s 72 slaves, valued at $64,800 appear in the Freestone County Tax Roles for 1864. An R. A. Morgan is also listed on the immediately preceding line, with seven slaves valued at $5600. Sanderson is also listed in weaver1945, 109, as a Mississippi planter who owned around $222,000 worth of property in Louisiana.↩

Could be a reference to Henrietta Wood. But Gerard Rickey notes in an email from November 23, 2016, that there is also a Henrietta mentioned in the memoir of James Brandon’s son Gerard Brandon (the nephew of the GB who owned Henrietta Wood). She is described as the family’s “faithful colored servant Henrietta. (She is still living this October 6, 1932. She must be about 85 years old now.)” If some of the enslaved people owned by James Brandon were also taken to Texas by Gerard, it is possible that this is the woman referred to in the journal, who would have been a teenager at the time. See Gerard Brandon, The Brandon Family, ed. Daisy Patterson Brandon Dale (Natchez: Daisy Patterson Brandon Dale, 2007), 72.↩

Williams may be the Mississippi-born Walter Williams who died in 1959 at age 117, though that claim has been questioned.↩

Phoebe appears to have been owned by Brandon’s brother Dr. James C. Brandon. A letter Cornelia Jane Shields to James Brandon’s wife states that “Mr. Brandon told me that Mr. Poole was offered $2000 in gold for Phoebe on his way to Texas, but he was on ahead of wagons and negroes and did not hear of it until too late. What a pity, that amount would have supported you during the war. It would have bought 20,000 in Confederate money at that time. Phoebe is living with a good family for her food and clothing only. She has learned to weave and is well satisfied your brother[-in-law] says.” See Gerard B. Rickey and Alan C. Rayne, ed., “‘I Will Write if I Have to Use a Stick’: Letters from Home—Cornelia Jane Shields’ Letters to her Children, 1864-1865” (University Park, Tex.: Estate of Sara Brandon Rickey, 2000), 79, available at Historic Natchez Foundation.↩

In 1872, Brandon was still in a legal dispute over an assumption of debt on a plantation he purchased in Tensas Parish (LA) from Hughes, who moved to Texas in 1862 or 1863. See menn1964 for more information about this holding.↩