Henrietta Wood

Henrietta Wood was a free African-American woman in Cincinnati who was tricked into entering Kentucky in 1853, where she was kidnapped and sold into slavery.1

Born a slave in Kentucky and owned first by the Tousey Family, Wood was manumitted in the 1840s by a Kentucky woman whose relatives disputed the legality of the manumission; see Cirode Family for details. The younger family members accepted money from Zebulon Ward, who orchestrated Wood’s kidnapping and sale to Lexington slave traders.

An attempt by local abolitionists to stop the sale failed, and Wood was eventually sold in Natchez to Mississippi cotton planter Gerard Brandon, who removed her to Texas in 1863. After the war, Wood brought suit against Ward for her kidnapping, asking for $15,000 to $20,000 in damages and lost wages. In 1878, a U.S. Court awarded her $2,500, upholding a lower court’s decision in Wood’s favor; see Wood v. Ward. She and her son Arthur H. Simms later settled in Chicago, where she died in 1912.

Names

It is difficult to know how and when Wood acquired her surname, and this is connected to difficulties in determining the exact circumstances of her birth. See 20160630 - Speculations on a Surname.

The death certificate for Arthur H. Simms gives her name as “Hattie Woods.”2

Autobiographical Narratives

In 1876, Wood gave a nearly 4,000-word account of her life and ordeals to Lafcadio Hearn, at that time a reporter for the Cincinnati Commercial, which I’ll refer to on this page as her 1876 narrative.3

In 1879, after her victory in court, Woods told her life story again to an unnamed interviewer (pseudonym “Cincinnati”) who published her narrative in the Ripley Bee, always under the headline “Kidnapped and Sold into Slavery.” The interview was serialized in four parts, but I’ve only found the final three, which will be abbreviated throughout this page as follows:

- RB1: first part of narrative, likely published February 20, but issue not extant

- RB2: Ripley Bee, February 27, 1879, link

- RB3: Ripley Bee, March 6, 1879, link

- RB4: Ripley Bee, March 20, 1879, link

The agreement between the details in these narratives is remarkable, even though they were separated by three years and told to different interviewers. This argues for a substantial role played by Wood in crafting her story.

Pre-1853 Life

Boone County, Kentucky

In 1876 Wood said she was “born on a farm in Boone County, Kentucky, right opposite Lawrenceburg,” and was owned by Moses Tauser until sold by his son, whose name she thought was “Homer.” In RB3 she recalls herself and her siblings being sold away from her mother and father by “young master Touci,” and her interview also suggests that her parents were known as Bill Touci and Daphne Touci.4 All of these details line up with an identification of her owner as Moses Tousey, whose son was Omer. See Tousey Family for details.5

Her birthdate varies in the records:

- 1818, according to her death record

- 1820, according to the 1910 census

- 1820, if calculated according to her 1876 memory of being sold as a fourteen-year-old upon the death of Moses Tousey, who died in 1834

Louisville, Kentucky (1)

Wood lived on the Tousey farm until she was, by her 1876 telling, fourteen years old. A division of the property around the time of Moses’s death led to her sale to “a Mr. Henry Forsyth, for $700,” in Louisville, while her siblings were sold to other buyers. See Henry Forsyth for more details on new owner.

Forsyth then sold her to William Cirode, a Frenchman, for what Wood recalled in 1876 as a sum of “$700 or $800,” probably in 1837 or 1838. See Cirode Family for details.

New Orleans, Louisiana

According to her 1876 narrative, Cirode took Wood to New Orleans on the steamboat “William French.” She worked for Cirode, being “pretty well treated,” for seven years in cooking and housework. See Cirode Family for details on the family’s moves.

Louisville, Kentucky (2)

In the mid-1840s, Jane Cirode (William’s wife) returned with Wood to Louisville. There she remembered being hired out to several people:

- “first to a man named Lyons, for housework” (see 1876)6

- “afterward to Mr. Bishop who kept the Louisville Hotel,” where she worked “as cook and chamber maid for four years” (see 1876)

- also to “lawyer Thurston” (likely Charles Mynn Thruston), according to RB3

One advertisement placed in the Louisville Courier in June 1844, around the time Wood may have returned to Louisville, mentioned a “likely negro woman” available for hire “for the balance of the year.”7 Another, placed in 1845, advertised “for hire, a negro woman, who is an excellent servant and a good cook and washer.”8

Cincinnati, Ohio (1)

But eventually (in 1847?) Wood joined Cirode in Cincinnati. A Vermont newspaper reported on March 5, 1879, that Wood and her mistress, Mrs. Cerode, relocated to Cincinnati from Louisville in 1847. The Wood v. Ward judgment also says the move (by Mrs. Cirode, in this case) took place in 1847, and that in Cincinnati, Cirode “executed and delivered to the plaintiff a formal instrument of emancipation.”9

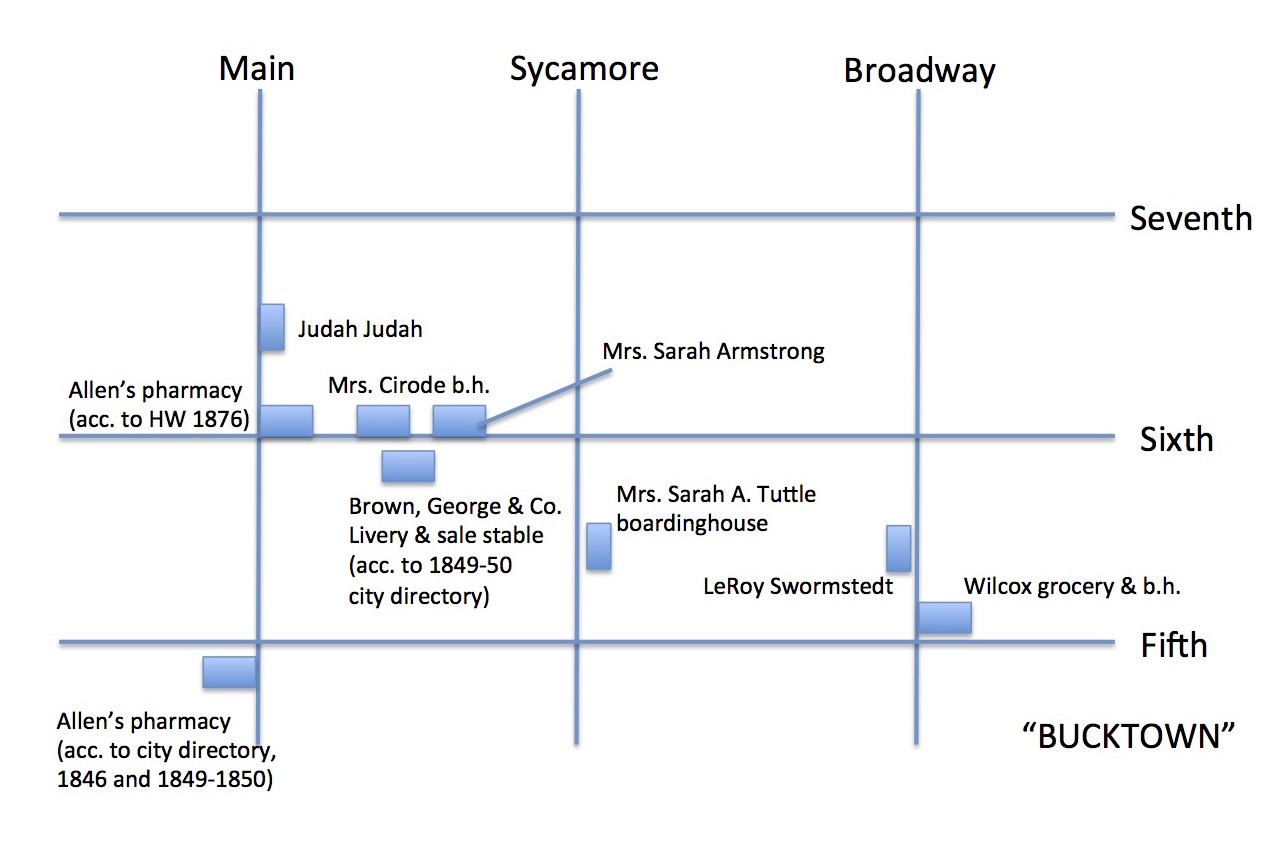

Sketch of Wood’s neighborhood

In 1876, Wood recalled her move to Cincinnati and some of the people she worked for:

I did no work for some time after I came back to Cincinnati, because I got very ill, and my mistress had to pay out a deal of money to old Dr. Mussey [spelling?] for attending me. He got me right well at last and I went to work for my mistress, Mrs. Jane Cerrode, she was keeping a boarding house then on Sixth street, next to Allen’s drug store. Allen’s drug store used to be at the northeast corner of Sixth and Main and my mistress’ boarding house was on the north side, between the drug store and where Judah’s barber shop is.10 After I had worked at cooking and washing in the boarding house for one year, my mistress gave me my freedom, and my papers were recorded. I worked for her two years more, but she would never pay me regular wages–only gave me a little money from time to time. So I left her at last.

She also remembers being sick when she first arrived, and was tended to by a Dr. Mussey, likely Reuben Dimond Mussey.

After this, she recalls working for several boarding houses or employers:

- Mrs. Tuttle (possiblly Sarah A. Tuttle, a native of France listed in Williams’ 1848-1849 directory as keeper of a boarding house at “East side Sycamore, between 5th and 6th, next to Franklin Hall.”11

- Preacher Swampson, possibly a misspelling of Rev. Leroy Swormstedt, a Methodist minister and book agent who lived on Broadway between Fifth and Sixth (see 1846 and 1849-1850 city directories; the 1850 census lists a German teenager as a domestic servant in his household

- Mrs. Wilcox, “who kept a boarding house at Fifth and Broadway” (possibly related to the famous black grocer Samuel T. Wilcox, who also operated his firm at that corner, and is described as a “steamboat steward, 5th bw Broadway and Pike,” in the Ohio Name Index?)

- Rebecca Boyd

In her 1876 narrative, she also recalled seeing a court house fire during this time and hearing that “the big book in which all the freed niggers’ papers were recorded was saved and taken to Columbus.”

Kidnapping and Enslavement

In June 1853, Wood was living as a free woman in Cincinnati when she was kidnapped, taken to Kentucky, and enslaved. That same month, Rebecca Boyd and an African-American man named Gilbert were arrested and held to bail for the kidnapping.12 They were held by Esquire Childsey.13 A man named Frank Rust was also implicated in the kidnapping. And the arrest of Boyd and Gilbert were mentioned in Frederick Douglass’ Paper, June 24, 1853.14

See Cincinnati Gazette for details of the criminal trial, which ended in acquittal. The Anti-Slavery Bugle (Ohio) reported on January 7, 1854 that the Criminal Court in Cincinnati acquitted “Rebecca Boyd,” Frank Rust and John Gilbert for the accused kidnapping of a Henrietta Wood. The trial revealed additional details about the case, including that Wood had been persuaded to enter a carriage in Cincinnati, Ohio, by the accused, and then taken out of the carriage in Kentucky by a man “who represented himself as sheriff.”15 In the trial, the defendants claimed Wood was a slave sold to Frank Rust–Mrs. Boyd’s boarder–by a Mr. Ware.

All the evidence suggests that Wood was lured into a hack in Cincinnati. She mentions a hack drive in RB2, and also in 1876, which gives details about what Rebecca Boyd said to her and about the first night of her kidnapping. See also 1876 narrative for corroboration and more detail, as well as Covington Journal, April 8, 1876, p. 2, column 6, which says Frank Russ was probably Frank Rust, “who died three or four years since” and identified Willoughby Scott (also implicated in the kidnapping) as “then of Bourbon.”16

Wood’s kidnappers took her first to Florence, according to RB2 and 1876. There the son of a landlady (unnamed, but in RB3 gives him the name Williams) talked to Wood and found out about her kidnapping, while Bolton (another name implicated in the kidnapping) and Scot had left her there to go to Burlington for some more slaves. See Jonathan Williams for potential identification of the man who helped her.

In 1876, Wood gave some details of her talk with Williams, noting that she told the man that in Cincinnati she knew “Preacher Tuttle” and “Leonard Armstrong,” whom Williams also knew or knew of.17

Their conversation was cut short by the return of Bolton and Scot who immediately put Wood on the Lexington stage and took her to the “slave pen” of Lewis Robards.18 Wood was taken into the “part of the house where Robards lived with a colored woman” in order to prevent visitors to the pen asking questions about where she had come from. She remained there for an unspecified amount of time, sewing clothes for those in the pen (see RB2 for descriptions of it) and eating meals in Robards’ kitchen, until one day when she saw Williams, the man from Florence, through the window. Sensing trouble, Robards put Wood in a buggy driven by an overseer who took her thirty miles from there, ostensibly to do some sewing work for a “Mrs. Fogles.”19

Wood remembered the ride from Lexington in RB3:

As we drove along the road, the birds chattering among the trees, the crow was cawing, the squirrel was running through the woods–all seemed mocking me in the enjoyment of their freedom. Even the horses in the fields came galloping to the fence to take a look at me; then with head and tail up, trotted nimbly by our side till a partition fence in the meadow brought them to a stand still. I seemed to be the worst slave of them all.20

In 1876, she also said that after reaching Fogles, she was taken to Harrodsburg.

While she was away, according to RB3, the Florence landlord (Williams) had gone to get “an officer” and returned to Robards’ pen. She remembered this officer in 1876 as Sheriff Rhodes, and Fayette County Court Order books confirm that “Waller Rodes” was the county sheriff at the time.21 He also questioned the driver from Florence. (How Wood knew this is unclear; informed later? or interpolation of interviewer?) But in the end, according to Wood’s memory, Robards was ordered by a court to bring her back to Lexington and “turn me over” to the slave pen of William Pullum. See Griffin and Pullum.

There, according to RB3, Wood was actually visited by her mother, who “didn’t know I had ever been free, but supposed I had fallen into the trader’s hand,” and who informed her her father was dead. In 1876, Wood also said that she was “kept in the jail for a whole year, and the sun never shined on me all that time–never once.”

According to RB3, “some kind of suit was then commenced in court,” circa June 1853. Wood remembered her lawyers as being a Mr. Kinkead (this was George B. Kinkead) in Lexington, and John Jolliffe in Cincinnati.

The case commenced when Wood’s lawyers filed a petition in the Fayette County Circuit Court “for the purpose of regaining her liberty.” Robards was initially the defendant, but “an interlocutory order was soon after entered in the cause, substituting the defendant ‘Zeb Ward’.” Ward claimed “that the plaintiff was not a free woman, but his slave.” A final decree was made on June 24, 1854 in favor of Ward, dismissing Wood’s petition. But Wood’s lawyers appealed to the Court of Appeals, which found on January 20, 1855, that there was no error in judgment at the lower court. See Wood v. Ward for details of the case.

In 1876, Wood recalled being taken by Zebulon Ward to the Kentucky penitentiary after her trial, where she was forced to be a nurse for Ward’s children. Quarrels ensued with Ward’s wife over her care for the child, which led to threats of punishment for Wood. Interesting details about Wood’s retorts to Ward, who eventually decided to sell her.

Mississippi

According to later litigation between Wood and Ward, Ward sold Wood to “one Wm. Pulliam” (Griffin and Pullum) who then sold her to Gerard Brandon, shortly after the decision of the Appeals court in January 1855.[See Wood v. Ward.] Pullum was one of Kentucky’s most active slave traders. Lewis Robards, who owned the private slave prison that first held Wood, was also a well known Kentucky slave trader. See also clark1934 and coleman1938.

In RB4, Wood described her experiences after arrival on Brandon’s cotton plantation, where she was initially forced to work in the fields and frequently whipped before “they changed my work to the house.”22

In 1876, there are also vivid descriptions of violent abuse on Brandon’s plantations at the hands of overseers named Bob Sandford, Bill Gates, Tom Lyles, and Moore, and at the instigation of Brandon’s wife.23 (Note that a check by Gerard Brandon to a B.J. Sandford dated “Cedar Grove Place, February 6, 1862,” appears in Historic Natchez Foundation records.)

Texas

During the Civil War, Wood became part of the wave of Refugeed Slaves to Texas. In RB4, she reported that “when the news came to master that the Yankees were coming toward us his wife made him take us to Texas. 500 of us walked through.” Like many enslaved people moved to Texas, Wood recalled being sick on the journey and for a long time thereafter. This part of the narrative also reveals for the first time that Wood had a child.

Wood may be the Henrietta mentioned several times in the diary of Gerard Brandon. See that page and RB4 for more information about her likely movements in Texas, where shre remained “for three years after the emancipation proclamation.” At this point Brandon (or perhaps the overseer he had left behind) said that if Wood and other freedpeople “would work for him three years he would take them back to Tennessee [sic]. We all took up the line of march and came back to Natchez with him. I stayed there three years, and then returned to old Cincinnati.”

Wood’s chronology here implies that she remained in Texas until 1866, and then in Natchez until 1869, though some of the stories about her in the national press in the 1870s claimed that she had remained in Texas until 1868 or 1869.

A reporter’s concluding remarks in 1876 confirm this basic outline, adding that Brandon offered to bring Wood back to Mississippi if she would promise to work for him for three years. She kept the promise, never being paid, but “raising hogs and chickens for market,” she saved $25 “with which she paid her passage and that of her only child, a boy, back to Cincinnati.”

Cincinnati (2)

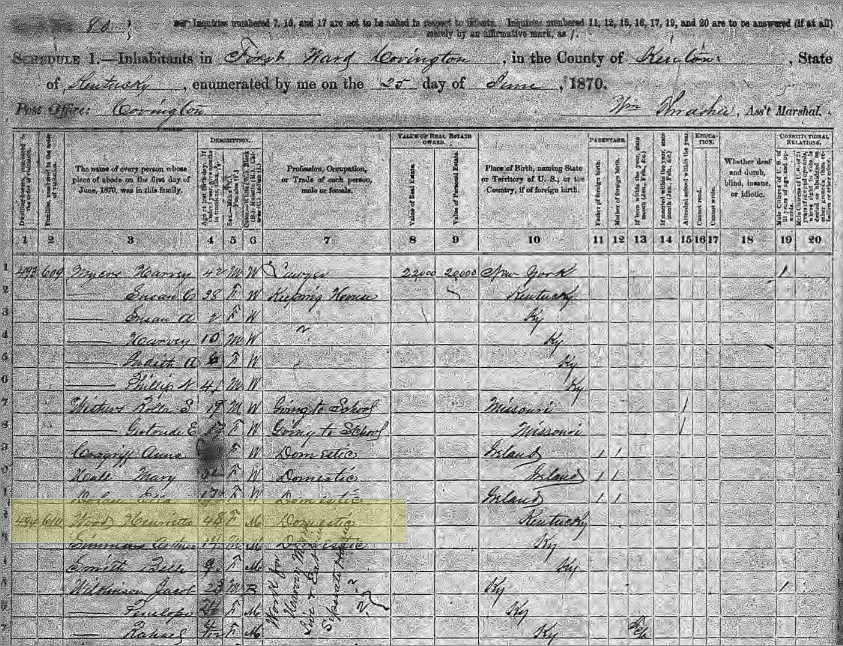

Sometime after the war, apparently in 1868 or 1869, Wood returned to Cincinnati. In 1870, she appeared in the census as a 48-year-old Henrietta Wood living in Covington, Kentucky, just across the river. She is identified as “mulatto” and as having been born in Kentucky. The census also says that Wood and the others in her household “work for Harvey Meyers, Live and eat in separate house.” This is the Harvey Myers also mentioned in RB4.

Image of 1870 Census with Henrietta Wood highlighted.

By 1876, when she was interviewed for the Commercial, Wood lived in a house at 19 Harrison St. That was also her address according to each of the city directories from 1875 through 1880—all of which identified her simply as “widow” and listed her as “Henrietta Woods.” Arthur H. Simms is listed at the same address in the 1875 directory as a “coachman”; he is gone the following year, but reappears in 1879 at the Harrison address (without an occupation). By 1881, both Wood and Simms no longer appear in the Cincinnati directory. The site of No. 19 Harrison appears to be occupied today by the headquarters of Proctor and Gamble.24

With Myers’ help, Wood filed suit against Zebulon Ward in 1869. See Wood v. Ward for details of the case. A report in the Cininnati Commercial on January 15, 1871 (available in AHN), summarized Wood’s case, which sought to recover “$20,000 damages” and had been transferred from the Superior Court to the United States Court, “where the petition was filed yesterday.”

The plaintiff says that in the year 1853, and for many years previous thereto, she was a free mulatto woman, residing in Cininnati, and that the defendant, Zeb. Ward, together with Rebecca Boyd, kidnapped and abducted her from her place of abode, to be delivered to the defendant, Ward, in the State of Kentucky, the defendant knowing her to be a free woman and a resident of Cincinnati.

The plaintiff further alleges that Ward kept her in bondage seven months, and then sold her to William Pulliam, a slave trader, who took her to the State of Mississippi, and sold her to one Girard Brandon for the sum of $1,050. The said Brandon forced and compelled her to labor on his plantations in Mississippi and Texas as a common field hand for fifteen years.

The plaintiff further alleges that by reason of being held in slavery, as aforesaid, she has been deprived of her time and the value of her labor, worth at least $500 per year, and also that during that period, she was subject to great hardships, abuse and oppression, and was prevented from returning to her home until April, 1869.25

The same report listed Wood’s lawyers as Lincoln, Smith, Warnock & Stevens and Henry Myers, with Hoadly, Jackson and Johnson representing Ward.26

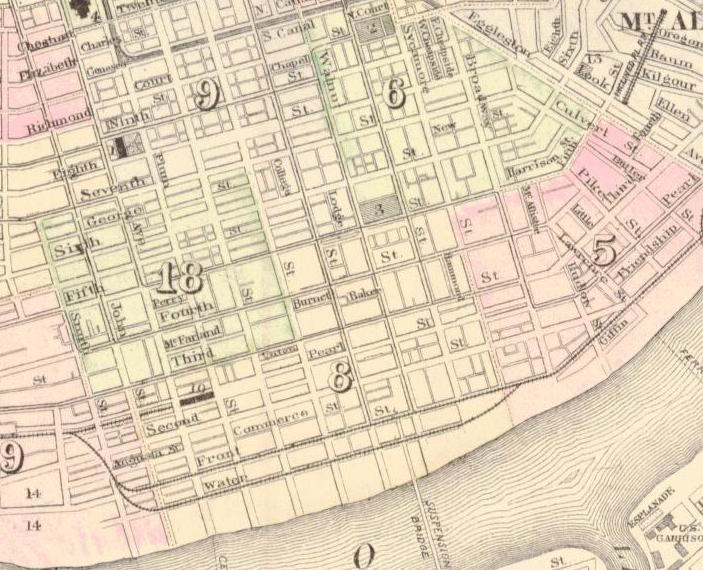

Cropped section of Gray’s New Map of Cincinnati (1876), showing Harrison Street in southeast corner of the Sixth Ward. Wood’s address is given as No. 15 Harrison St. in 1876, and she is listed as “Woods Henrietta, widow, h. 19 Harrison” in the city directory.

The Cincinnati Daily Gazette of April 23, 1878, reprinted excerpt from the New York Times:

We would willingly close this dark chapter in American history. But Henrietta Wood, who, after twenty-five years, has been avenged of the man who stole her, has opened it again. And every man who comes to Congress whining about the losses of the South, sustained through the destruction of property [in human slavery, opens it. The loss of property] by the proclamation that chattelhood in man has ceased to exist may have been great. But there is another side to the question. The United States Government may be asked to make good the loss of those who property was suddenly clothed with the right of manhood. But who will recompense the millions of men and women for the years of liberty of which they have been defrauded? Who will make good to the thousands of kidnaped freemen the agony, distress, and bondage of a lifetime? Let us have both sides of this long unsettled account.27

One of the longest summaries of the suit appeared in The Somerset Herald (Pennsylvania), which describes Wood as “six feet tall, of powerful frame, black as night, and over sixty years of age.” This is also the report indicating that her “only son … was with her in the court room yesterday.”28

For more on the suit, see Wood v. Ward and spreadsheet of national newspaper coverage.

Post-Verdict Life

The 1876 narrative notes that Wood’s son, Arthur H. Simms, is “now in Chicago, doing well,” but does not name him.

In the 1880 census, Wood appears as a boarder in the Chicago household of a Charles Ross together with her son, living at 133 Fourth Avenue. She is listed as “widowed.”

In the 1900 census, she is listed as having had four children, only one of whom is living.

In the 1910 census, she is also in the household of an “Arthur Simms,” born in Mississippi.

In a 1912 death record from Cook County for a Henrietta Wood whose birthplace is listed as Woodford County, Kentucky, and whose parents (William and Daphne Williams) correspond to the “Bill” and “Daphne” mentioned in RB3. Her full death certificate lists her as a resident in Chicago for 32 years but a resident of 4917 Dearborn for only the last two years. Both her “former occupation” and “last occupation” are given as “House Keeper.” The cause of death is listed as “aortic insufficiency.”29

Wood was buried in Lincoln Cemetery.30 Her name was listed under “Deaths of the Week” in Chicago Defender, December 7, 1912, with the address listed as 4917 Dearborn Street and her date of death as December 1.

Miscellaneous

- Blog post about the Wood v. Ward case

- Transcription of an 1878 New York Times article on Wood

- Notice of the case in The Friend

- The Centennial History of Cincinnati referred to the case as “an echo of slavery times”

- Brief note in an 1878 newspaper suggesting that “Zebulon may congratulate himself on having gotten off cheap”

- There’s a line that appears to read “Woods Henrietta mrs” in a list of letters left at the Louisville post office; see Louisville Daily Courier, September 16, 1852, p. 3, on Newspapers.com.

- A “Henrietta Woods” is listed under “Illinois” as the recipient of an approved widow’s pension in the Chicago Daily Inter Ocean, October 16, 1891, p. 12.

- Brief post about Wood by Reinette Jones, dated August 19, 2016, including reference to an article about Frank Rust

- Mention of Wood’s victory in a pamphlet on emigration from 1878

- The Chicago Inter Ocean headlined the case “The Price of Liberty” and described it as “a pointed commentary on the kind of government we had under the rule of the old pro-slavery Democracy.” It caustically depicts Ward as kidnapping Wood for “a little pocket change.” Though it mangles some details, it connects the case to Dred Scott: “A negro had no rights which a white man was bound to respect, and he was enabled to get her to Texas without difficulty, where he sold her to a planter.” She was “freed by the fortunes of war,” but “The want of money to pay her way North compelled her to remain and work for a considerable time after she was free,” by which point she was “prematurely old and decrepit from the hardships of her enforced bondage.” The Ocean also concluded: “It should have been $25,000. The kidnapper is said to have grown wealthy off of the price of this free woman.”31

Spreadsheet of Newspaper Articles

Below is an attempt to capture information about any newspaper articles that mentioned Wood’s suit against Ward.

These articles were collected by Caleb McDaniel and by Christina Regelski and Clair Hopper as part of RA Assignments. A few article titles and citations were provided by M’Lissa Kesterman at Cincinnati History Library and Archives.

Thanks to Richard Blackett for the tip about Wood’s story, and for the pointer to look in the February 27, March 6 and March 20 issues of the Ripley Bee (Ohio) for her account.↩

Medical Certificate of Death no. 73178, State of Illinois, downloaded from Cook County Genealogy website.↩

“Story of a Slave,” Cincinnati Commercial, April 2, 1876, p. 2, link.↩

Wood’s death certificate gives her parents’ names as William Williams and Daphne Williams.↩

A reference to an “old woman” named Daphney, now “slave of Sam’l Beale, who is now in Alabama,” appears in Louisville Daily Courier, October 7, 1856, p. 3. But there is also a black woman named Daphne Tousey, aged 70 and born in Virginia, living with an elderly white woman named Eleanor Fugate in Scott County in 1850, which would be just north of Lexington.↩

Several hits for Lyons in the 1844 Louisville city directory.↩

Placed by James Barbee, address on Seventh between Walnut and Chestnut, Louisville Courier, June 14, 1844.↩

Placed by James H. Bagby, General Agent, Louisville Courier, February 20, 1845. Another ad around this time placed by Bagby gives an age of thirty-five for one of the women he is hiring: unclear if it’s the same one.↩

It seems unlikely that the manumission register survives, considering an 1849 fire at the courthouse in Hamilton County. See also emails from Tutti Jackson and Jack Dempsey in November 2015 for information about the very rare surviving registers. Wood herself remembered the fire in the 1876 interview. Salmon P. Chase noted that the 1849 fire was greeted by Cincinnatians who viewed it as a “Nuisance.”↩

Judah’s barbershop appears in the 1849-1850 Cincinnati directory on the east side of Main, between 6th and 7th. A Judah barber shop appears in the 1879 city directory for Cincinnati, available on Fold3.↩

See also Google Books.↩

Daily Dispatch (Richmond, Va.), June 10, 1853, Chronicling America link.↩

“Kidnapping Case,” Baltimore Sun, June 9, 1853, AHN.↩

“KIDNAPPERS ARRESTED. - A white woman named Boyd, and a colored man named Gilbert, were arrested in Cincinnati June 8, on a charge of kidnapping a free colored girl named Henrietta Wood. The case excites a good deal of interest.” See Accessible Archives database.↩

“That Kidnapping Case,” Anti-Slavery Bugle, January 14, 1854, Chronicling America link.↩

A Willoughby Scott appears in Harrison County census of 1840 with 16 slaves; see Ancestry.com. He is probably the W. S. Scott, married to Margaret, who appears in Bourbon County as a farmer in 1850. Some slaves were sold for his benefit even when he was a child, according to this law.↩

Leonard Armstrong may be the one who served in the Ohio House of Representatives in 1830. Not sure about the Tuttle family, but see this potentially relevant genealogy. There seem to have been abolitionist Tuttles, including a Lloyd Garrison Tuttle living in the Western Reserve. There was also a Dennis P. Tuttle who kept an inn in Cincinnati called the City Hotel on the south side of Fourth between Main and Walnut, which would have been very close to the boarding house of Rebecca Boyd.↩

On Robards see coleman1938 and clark1934.↩

Quotes in this paragraph from RB2. See also 1876 narrative for the same basic timeline but with some more details.↩

Fayette County Clerk Order Books 13 and 14, Kentucky Department for Libraries and Archives.↩

The narrative gives good examples of the kinds of physical reconfiguration and labor discussed by baptist2014 and johnson2013 in their histories of the cotton kingdom. See also pargas2015, 135-148, on adjustment of Upper South slaves to cotton.↩

On violence of mistresses, see glymph2008, pargas2015, 210↩

Wood and Simms do not appear to be in the Cincinnati directories prior to 1875, which may indicate they continued to live adjacent to Harvey Myers until his death in 1874. Other people living at the address in 1876 include a porter named Elijah Bullett and a widow and laundress named Charity Robinson or Robson. In 1877, the other occupant is John Freeman, barber. In 1878, it is George Moore, barkeeper. In 1879, they are Mary E. Cumberland and Henry Taylor, “jobber” (who also appears at the address in 1880.↩

“A Colored Woman Kidnapped and Taken into Slavery Wants $20,000 Damages,” Cincinnati Commercial, January 15, 1871. The Cincinnati Daily Gazette of January 16, 1871 (AHN) also reprinted it under the headline “The Dregs of American Slavery.”↩

“A Colored Woman Kidnapped and Taken into Slavery Wants $20,000 Damages,” Cincinnati Commercial, January 15, 1871.↩

The original Times story appeared on April 21, 1878. This longer report links Wood’s case to several other kidnapping cases in Ohio.↩

“An Old Colored Woman’s Suit Against Her Kidnapper,” The Somerset Herald, April 24, 1878, Chronicling America link.↩

Full certificate of death, Registered No. 30774, downloaded from Cook County Genealogy site.↩

Per email from Eliza Hill of Dignity Memorial (which now manages Lincoln) on October 24, 2015, Wood’s grave has now headstone, but a burial record card shows that hers was burial number 462 at the cemetery, and her grave can be found in Lot 3, Section 3, Row 1, Grave 6. The burial record card gives her address as 4913 Dearborn Street, the date of death as December 4, 1912, and her age as 94 years.↩

“The Price of Liberty,” Inter Ocean (Chicago, Ill.), May 3, 1978, p. 4, found on Newspapers.com.↩