Cirode Family

Multiple sources show that Henrietta Wood moved from Louisville to Cincinnati with a “Mrs. Cirode” and was manumitted there around 1848. My research suggests that this was Jane M. Cirode, who was the wife of William Cirode from France. Cirode’s legal right to emancipate Wood was later challenged by her children, which apparently doomed Wood’s 1850s case in Kentucky and became an issue in her 1870s case, too. (See Wood v. Ward.)

Jane Cirode’s name is spelled various ways in different sources:

- City directories and census records alternate between “Cirode” and “Cerode.”

- The U.S. Circuit Court case file for Wood v. Ward names Wood’s late mistress as “Jane M. Corodes of Cincinnati, Ohio” in Ward’s reply to the plaintiff’s petition.

- Wood’s 1876 narrative refers to her as “Mrs. Jane Cerrode.”

However, Wood’s own 1876 narrative helps to solidify the identity of various family members, beginning with her reference to Mrs. Cirode’s husband William Cirode as a “Frenchman.”

From France to Kentucky

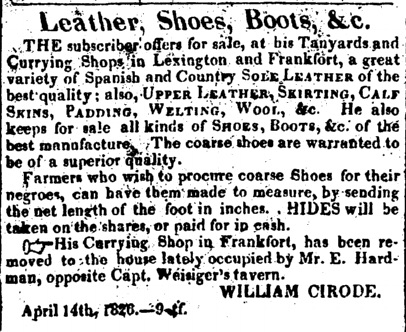

Ad placed by William Cirode in Frankfort Argus, May 31, 1826. From GenealogyBank.com.

According to saugera2011, Guillaume Cirode was a twenty-four-year-old “tawer from Nantes” who was in Lexington, Kentucky, by 1816, and whose brother was Yves Cirode. Richard Stevens has a dataset for an 1818 street directory in Lexington that lists William Cirode as a “skin dresser” and places his establishment on “Main, nr Catholic burying” ground.

An early ad for his tannery appeared in the Kentucky Gazette for April 14, 1820.

Cirode was part of a larger diaspora of French emigres in and around Lexington and Louisville, and he appears to have joined, along with the Lexington silversmith Antoine Dumesnil (or Dumenil), as a shareholder in the so called Vine and Olive colony, acquiring a 120-acre grant of land near Mobile, Alabama. But he appears to have never moved there, like most of the company shareholders.1

In 1818, Cirode married “Miss Jane White, daughter of Daniel White, of Fayette county.”2 The father of the bride is possibly the Daniel White in the 1810 Census for Fayette County.

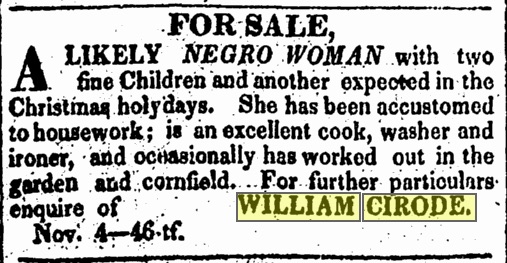

In 1826, Cirode placed an advertisement for the products of his “Tanyards and Currying Shops,” including “Leather, Shoes, Boots, &c.,” in the Frankfort Argus, suggesting that he had a location there, too. This ad made a special appeal to slaveowners: “Farmers who wish to procure coarse Shoes for their negroes, can have them made to measure, by sending the net length of the foot in inches.”3 In 1828, Cirode placed an ad in the Lexington Reporter for the sale of “a likely NEGRO WOMAN with two fine Children and another expected in the Christmas holydays. She has been accustomed to housework, is an excellent cook, washer and ironer, and occasionally has worked out in the garden and cornfield.”4

Yet Cirode was not without enemies; according to an ad he placed in 1824, he was assaulted by some unnamed ruffians, and he offered a $50 reward for their capture:

It is ever unsafe to overleap the boundaries of the law. In troublesome times dangerous precedents are established. Some time since certain suspicious individuals, supposed to be incendiaries were punished without lawful authority; whether the real offenders were selected will never be known; but certain it is, that a practice was introduced that may be carried to the most dreadful lengths. I am a foreigner. I speak the language of this country badly; therefore associate but little with the world. My enemies admit that I am industrious: and I have the satisfaction to know that my exertions have been rewarded by an increase of property. But somehow I have been so unfortunate as to excite the envy and malignity of certain evil disposed persons, who not daring to meet me in day light, have been base enough to send hired ruffians to drag me from my house at the silent hour of night, and to commit violence upon my person.—I am to be sure a friendless foreigner, what I suffer may be thought an unimportant matter; but where is the thing to stop? Who is safe?

Few men are without enemies; what a horrid state of society will exist when every base hearted individual who may choose to take offence, at his neighbour, can enlist a few irresponsible bravo’s, fellows without character or property, and who by their assistance may tear a citizen from his family and inflict the most inhuman torments on their victim. These things are done in a manner, which in a great measure eludes detection, and considerable exertions are necessary, to discover offenders. However on my account perhaps but little effort will be made. I have not mixed witho society to obtain friends. I have simply attended to my tan yard and family, and few concern themselves about me or my fate. But if society heedlessly suffers the perpetration of such infamous outrages on the obscure and unassuming, is there not reason to fear that more conspicuous persons may fall victims to this nocturnal brutality? If I might venture an opinion, I would suggest that the Town authorities should make an effort to bring this class of offenders to justice.

But as no such aid is offered me, I will use the little means subject to my own control—my money. I therefore offer FIFTY DOLLARS in currency, to any person who will discover and convict before the proper tribunal, the persons who perpetrated the outrage committed on me last Thursday. These who have knowledge of the fact may call on me and communicate the desired information, and their reward shall be punctually paid as my enemies will not question, but that I comply with my engagements.5

Around 1828, Cirode decided to sell his tanyard in Lexington, offering it for sale with the stock as well as “5,000 yards of white JEANS for Negro clothing.”6

Advertisement in Lexington Reporter, December 10, 1828, from GenealogyBank.com

By 1830, Cirode appears in the 1830 census for Louisville, with a household consisting of one white female aged 30 to 39, four small children, and seven slaves (including one female under 10, two females aged 10 through 23, and one female aged 24 through 35). In 1840, his household still appears in the census for Louisville, but with only six white persons and no slaves.7 There is also a William Cirode listed in the Louisville city directory of 1832 on the northside of Market street between 5th and 6th streets. In the 1838 city directory, he still appears in Louisville, on the south side of Jefferson between 4th and 5th.8

An issue of the Daily Journal of January 2, 1837, also shows that Henry Forsyth, George Keats, and William Cirode were all voting members of the Mechanics’ Saving Institution of Louisville. (Also appears on December 29, 1836.) But by the February 22, 1837, notice, Cirode no longer appears on the list.

In 1840, Josephine Cirode, daughter of Wm. Cirode, married Robert K. White in “Jefferson, Kentucky.” It’s unclear whether this Robert White was at all related to Cirode’s father-in-law Daniel White.

From Kentucky to Louisiana

According to Wood’s 1876 narrative, shortly after purchasing her for “$700 or $800,” William Cirode took her “at once on the steamboat ‘William French’ to New Orleans, where he kept a retail and wholesale grocery store.” She recalled staying there for seven years.

Cirode apparently began planning his move to New Orleans in January 1837, when newspaper ads began to appear in the Louisville Daily Journal advertising that his store on 5th Street was available for rent.9 Beginning on March 6, 1837, a new ad began to appear in the Daily Journal (usually on page 2 or 3) placed by G. B. & R. J. Didlake explaining that they had “taken the Hide Store of W. Cirode, on Fifth Cross street, between Main and Water.” These ran almost every day through May 1837.10 A few months later, on October 23, 1839, William Cirode placed a notice in the Daily Journal that “I have appointed Mr. G. B. Didlake my agent to collect rents, &c. due me, during my absence,” indicating he was already gone.11

William Cirode also shows up in the 1840 New Orleans census for Ward 2, aged between 50 and 60, but with no slaves, and there is a white male in that age range in the Louisville household, too, suggesting he may have been double counted because of the move around this time. By 1841, notices appeared in the New Orleans Daily Picayune indicating that letters were waiting at the New Orleans post office for both William and Jane Cirode.12

Advertisements for W. Cirode “late of Louisville, Kentucky” run consistently in the New Orleans Commercial Bulletin from January to at least June 1838. They refer to Cirode as a Commission and Forwarding Merchant located at the corner of Commerce and Poydras Streets.13 Cirode also began to advertise specific goods, including tallow, tanners, vinegar, ox horns, raisins and sheep skins, in January 1838.14 A few ads specified vinegar from Cincinnati or Tampico hides.15.

Cirode formed a co-partnership with Matthew Starbucks Coffin in December 1838 to “carry on for their account in this city, the ‘produce business.’” Cirode contributed $10,000 in cash to capitalize the firm, while Coffin brought “his skill, credit, care and industry as a merchant.”16 The last few months of 1838 issues of the Commercial Bulletin are missing, but at least starting on January 1, 1839, Cirode advertises as “Cirode and Coffin.”17 They describe themselves as “Wholesale and retail Western produce merchants” on 19 Poydras Street. They run ads for flour, tanner’s oil, canvassed hams, and bacon sides and shoulders.18. But on January 10, 1839, the paper runs a notice that “the partnership heretofore existing under the name of CIRODE & COFFIN was dissolved on the 5th inst. by mutual consent.”19

Cirode returns to advertising as “W. Cirode” but still locates his business on 19 Poydras Street by January 10, 1839. These ads run until about November 16, 1839 and state that his business is in “Western produce.”20 He runs ads for lard, bacon sides and shoulders, flour, pork, rectified whiskey, brooms, mackerel, canvassed hams, and beef.21 While he continues to advertise his business generally until November 1839, his advertisements for specific goods stop around August 1839.

On May 21 and 22, 1839, Cirode runs an advertisement in the Commercial bulletin for the sale of a “negro girl, about 16[?] years old.”22. Cirode also runs an announcement from July 1-3, 1839 that advertises: “For sale or hire–a negro girl, 15 or 16 years old.”23

From a sampling of 4-8 issues per month, there is no evidence Cirode placed advertisements or any other notices in the Bulletin from 1840-1842 or in 1844. Online issues for 1844 stop in June. In 1843, Cirode still is not advertising his merchant business or specific goods but he does place notices concerning property. From July 14 to at least August 5,1843, a Wm Cirode places a want ad that expresses a wish to purchase–in cash–a “lot of ground of 4-5[?] acres, improved or unimproved, in the First or Second Municipality.” See, for example, August 1, pg. 3 on Google News.

I have poked around in a few issues of the New Orleans Bee (digitized) between 1840 and 1842 to see if Cirode took his advertising there, but without much luck so far.

A search for “western produce” in the Picayune shows that business in the sector was sluggish between 1839 and 1841.

Addresses

These are street addresses in New Orleans that I have somehow associated with Cirode. Some can be located on this 1845 map of New Orleans. Also see the Vieux Carre Survey.

| Date | Address Then | Address Today | Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1838 | 13 Poydras Street24 | Commercial | |

| 1839 | St. Joseph bw Camp and Magazine25 | Residential | |

| 1839 | 19 Poydras Street | Commercial | |

| 1841 | 19 Poydras Street | Commercial | |

| 1842 | 13 Conde Street26 | 117 Chartres | Unknown |

| 1843 | 56 Old Levee27 | 400-446 N. Peters bw St Louis and Conti | Commercial |

| 1843 | 243 Dauphin near DuMaine28 | 905-907 Dauphine | Residential |

| 1843 | 339 Burgundy29 | Unknown |

Named Slaves

Cirode purchased Caroline, aged 15, from Tilman Magruder & Co. in Louisville on March 9, 1837, for $550. Two years later, he sold her to William Erskine Camp for $650.30 This could be the Caroline referred to in the case of Edmund Bacond vs. William Cirode (see below).

Cirode purchased Elizabeth, aged 25, and her son James, aged 20 months, from William McMillan Jr. (agent of John Castillo) of Mobile Alabama, for $750, on December 26, 1839.31

Cirode shipped a slave named “Eliza” to Mobile on January 15, 1840, and slaves named “Phillis” and “Elizabeth” to Mobile on March 25, 1840, both from New Orleans.32

Cirode purchased Rispa or Ripa, aged 27, from Michael O’Connor of Mobile on February 4, 1840.33 He later sold Rispa to James Thompson Kelly.34

Cirode purchased Thornton, “a certain griff slave,” aged 21 years, for $800 cash on December 1840.35 He later shows up in Parish v. Cirode court papers, in an excerpt from Cirode’s account books that show he had hired out Thornton to his son’s Mobile firm.

Cirode purchased Margaret, aged 27 years, and Eliza, aged 9 years, from Thomas Atkins, “a free man of Colour of this City,” on May 6, 1843.36 Margaret was later sold to Samuel Bell by the sheriff of the commercial court of New Orleans after the jury found against Cirode in the case of Bell v. Cirode.37

Cirode & White

At some point, Cirode was joined in the Deep South by his son Daniel W. Cirode. In August 1839, there are ads in the Daily Journal placed by D. W. Cirode offering to rent “the dwelling house, No. 19, Jefferson st., bet. 4th and 5th sts.,” beginning in November.38

Around this time, Daniel W. Cirode joined together with his brother-in-law, Robert K. White, in a business venture operating between Mobile, Alabama, and New Orleans. A marriage record shows that in November 1843, Daniel W. Cirode married Mary Ann Smith in the Catholic Church in Mobile.39 A William Cirode appears on slave manifests for a couple of slaves bound from Pontchartrain to Mobile, Alabama in 1840, presumably shipping to his son and son-in-law.40 In 1842, this entry appears in the Mobile city directory: “Cirode & White, grocers, 63 commerce 60 front, Daniel W Cirode and Robert K White.”41

In 1844, both Daniel W. Cirode and Robert White appear again in the Mobile city directory edited by E. T. Wood, but no longer as a single firm.42

The Cirode-White firm was short-lived and had collapsed into insolvency by 1843.43 William Cirode had floated significant capital and goods to his sons (possibly totalling as much as $42,000, of which they paid back $31,000), and when they failed, the son’s creditors came for the father. One of the creditors filed a suit against Cirode in Parish v. Cirode, which contains more details about the collapse and gives a window into the family’s business dealings. (See also Bell v. Cirode, which contains evidence that Daniel W. Cirode was declared bankrupt by December 1842.)

Timeline

| Year | Month/Day | Event | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1840 | November | WC gives funds to C&W | A |

| 1842 | April 18 | WC tells Mobile County Circuit Court that C&W are indebted to him for $11,495, are about to remove; requests attach | A |

| 1842 | April 20 | WC “attaches” C&W goods; tells N.O. merchants the firm has failed | A |

| 1842 | May 10 | WC wins suit against C&W for $10,605 in Mobile County | A |

| 1842 | December 20 | Parish files suit against WC | A |

| 1843 | January 14 | Sheriff leaves summons at 243 Dauphin with Jane Cirode | A |

| 1843 | April 29 | Court finds in favor of Parish | A |

| 1843 | May 10 | WC appeals judgment for Parish with Pierre Roy as surety | A |

| 1844 | January 22 | Supreme Court upholds Parish | A |

| 1844 | January 25 | WC mortgages land to friend in New Orleans to hold it in “secret trust” for daughter | B |

| 1844 | March 11 | WC applies for a passport in Philadelphia | C |

| 1844 | May | After re-hearing, SC upholds Parish again | A |

| 1844 | September 7 | WC arrives in Philadelphia again on board brig Vulture from Santiago Cuba | D |

| 1846 | October | WC arrives in Philadelphia aboard brig Adele from Santiago Cuba | E |

SOURCES

A: Parish v. Cirode papers

B: James C. Johnston v. William Cirode, Louisville Chancery Court, KDLA (see below)

C: “United States Passport Applications, 1795-1925,” database with images, FamilySearch, https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:Q295-NYQ4, William Cirode, 12 Mar 1844; citing Passport Applications, 1795-1905, 14, NARA microfilm publications M1490 and M1372 (Washington D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.)

D: “Pennsylvania, Philadelphia Passenger Lists, 1800-1882,” database with images, FamilySearch, https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:K8CQ-DM8, William Cirode, 1844; citing NARA microfilm publication M425 (Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.). See also “Cleared” and “Arrived” in Philadelphia Public Ledger, September 7, 1844, which reports the boat left Santiago on August 17. According to July 18, 1844, edition of Public Ledger, the boat had left Philadelphia for Cuba on July 18. Both on Newspapers.com

E: Pennsylvania, Passenger and Crew Lists, 1800-1962, available on Ancestry.com. The National Archives at Washington, D.C.; Washington, D.C.; Series Title: Passenger Lists of Vessels Arriving at Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Record Group Title: Records of the United States Customs Service, 1745-1997; Record Group Number: 36; Series: M425; Roll: 63.

Breakup of Family

The financial trouble described above could explain why Wood remembers that William and Jane Cirode “quarreled at last, and the old man sold the store, left his wife and went back to France,” though not before “he gave his wife some blacks.” A letter from George B. Kinkead to William Stewart Bodley referring to Wood’s case suggests that Charles Mynn Thruston remembered a deed of trust that “conveyed the negroes” (including Wood) from an unnamed Cirode to Daniel Cirode “for the use of his wife.”

A William Cirode born in the 1780s shows up on several passenger lists from the 1840s, including for a vessel from Cuba to Philadelphia, and a vessel arriving in Baltimore. And a William Cirode applied for a passport on March 12, 1844, at age 59, suggesting it was the same person and he was already fleeing the country.44

Cases such as Roy v. Cirode show that Cirode’s creditors eventually traced the family back to Kentucky and filed suits to try to recover their losses, claiming that he had run off to escape his debts. At a tax sale in Louisville in January 1851, a lot owned by William Cirode on the southwest corner of Prather and Eleventh Streets was auctioned off because of failure to pay taxes dating back to 1847, further evidence that he never returned.45

In 1852, Cirode’s son William Y. Cirode wrote to the Passport office to inquire about whether a passport had been granted for the elder Cirode to Mexico in 1844 or 1845, asking for a reply to be sent to Cincinnati—perhaps an indication that he was trying to locate his father.

Back to Kentucky and Ohio

Robert and Josephine White

In the 1850 census, Robert and Josephine White show up in Covington, Kentucky, along with a boarder named Alexander Griswold and a five-year-old son (born in Pennsylvania), also named Robert. Robert White is here listed as having been born in England around 1815, and Josephine is ten years younger. Robert’s occupation is listed as “grocer,” and in the early 1850s, advertisements for his grocery store appear regularly in the Covington Journal. White is also listed as the owner of two slaves in the 1850 slave schedule: a woman around Henrietta Wood’s age and a three-year-old girl.

He repeatedly sent “presents” from his inventory to the editor of the Covington Journal: see “A Substantial Present,” Covington Journal, January 10, 1852; also in January 8, 1853.

After moving to Covington, one or both of the Whites occasionally visited Louisville.46

White’s grocery went under in July 1853. He listed in the R. G. Dunn & Co. Credit Report Volumes on a page titled “Traders out of bus. Kenton Co. Ky,” with this notation: “R. White. Covington. Grocery. July 5 ’49 to July ’53 thot good, but assigned and it is thot stored away his ppy [property].”47

This chronology aligns with the evidence from the Kenton County tax rolls. They show “R. White” in (May) 1853 owning 10 acres valued at $3,000; 1 store valued at $4,500; 1 piano, valued at $150; and no slaves. He no longer appears in the Kenton rolls for subsequent years.48

Neither Robert or Josephine show up in the 1856-1857 Covington city directory, but a Josephine White does show up on Clark Street in the 1861 city directory (PDF).

There is also a Josephine White with a son named Robert in the 1860 Census for Cincinnati whose ages and birthplaces match the family; perhaps by then Robert White had died.

Jane Cirode

Wood recalled in 1876 that after her husband’s departure in the mid-1840s, Jane Cirode “went up the river again to Louisville and from there to Cincinnati,” though not before hiring Wood out in Kentucky. (Daniel W. Cirode appears to have stayed behind in New Orleans.49) Wood joined Cirode in Cincinnati after about four years of being hired out in Louisville, perhaps in 1847 or 1848.

Around this time, Cirode begins to appear in Cincinnati City Directories together with a son, William Y. Cirode, who was probably born in Kentucky in 1834 according to the 1850 census. In 1849-1850 directory, “Mrs. J. Cirode” is listed as a boarding house keeper on north side of 6th, between Main and Sycamore.50

A Mrs. J. Cirode and Mr. Wm. Y. Cirode show up in the 1850-1851 Cincinnati City Directory, too, though this one locates her boarding house on the southside of Pearl between Race and Elm.

In the 1851-1852 directory, “Mrs. Jane Cirode” appears as a boarding house keeper at 60 w. 6th, and William Y. Cirode is listed as boarding with her. Finally, there’s a Mrs. Jane M. Cirode on 211 Elm and a Wm. Y. Cirode, bookkeeper, at 34 Pearl, in the 1853 Cincinnati City Directory.51

A Jane Cerode shows up as head of household in Cincinnati Ward 4 (born about 1797 in England) in the 1850 census, and the variety of people listed in her household (Wm. Y. and Louisa Cirode, but also Mitchell, Wetherly, Burns, Hemming—from Virginia, Ireland, and England) suggests it was the boarding house mentioned in the city directories.

Her return made it possible for her daughter Josephine and son Robert White (who had at some point returned to Kentucky) to contest her ability to manumit Wood.

Yet by 1857, Mrs. Cirode had died. A will index digitized by the University of Cincinnati lists an 1857 will in Hamilton County by Jane Maria Cirode in which the beneficiaries included Mary Louisa A. Handlen, William Y. Cirode, and Robbin White Jr.52 The Ohio, Wills and Probate Records, 1786-1998, database at Ancestry.com includes an index that says this estate (number 3780) was probated on January 27, 1857 and is recorded in vol. 9, page 202. Ancestry contains scans of this will book, described as Wills, Vol. 9-10, 1860-1864, in the same database. The will was probated before John Burgoyne in the Hamilton Probate Court. Mary Louisa Handlen is identified as her daughter and William Y. Cirode is her son53. Robbin K. White, Junior, is her grandson, perhaps in a misspelling or faulty transcription of Robert K. White, Jr. She wished her remains to be taken to Louisville “and interred where the relations of my husband are buried.” The witnesses for the will are Thomas J. J. Coppinger and James F. Wood, likely Catholic priests.

Miscellaneous

New Orleans Research

Cirode has several acts recorded in the Notarial Records of Joseph B. Marks, which do not have indices digitized. Examined Marks books from relevant years on site at Notarial Archives (NONA) on June 20, 2016.54 There is no listing for Cirode or Robert White in the digitized historical notaries’ indexes for New Orleans between 1837 and 1844, or at least the ones available online in Fall 2015.55

Using the comprehensive List of Notaries at NONA, here are notaries with records in the timeframe of Cirode’s time in New Orleans, but without digitized indices:

- Alphonse Barnett (1847-1873)

- Edward Barnett (1838-1872)

- Edward Duplessis (1843-1846)

- P. P. Labarre (1840-1850)

- Philippe Lacoste (1837-1862)

- Louis Maureau (1843-1846)

- Charles Boudousquieu (1837-1850)

- Achille Chiapella (1839-1857)

- Daniel Clark J. (1846-1849)

- Onesiphone Drouet (1844-1879)

- Hugues Pedesclaux (1829-1862)

- Felix Percy (1838-1862)

- Laroque Turgeau (1838-1844)

NONA archivist Sally Reeves says that the notaries most often used by Anglo community in slave sales include Edward Barnett, William Boswell, J. B. Marks, H. B. Cenas, William Christy.

Kentucky Department of Libraries and Archives

Because George B. Kinkead mentioned a deed of trust involving Cirodes, I tried to search for such a deed at KDLA, though it now seems possible such a deed might have been drawn up in Louisiana.

I found entries for Cirodes and Thrustons in the Deed Books Grantee Indices for 1838-1852 (Microfilm Reels 7035905-7035906), as well as the Grantor Indices for 1783-1865 (Microfilm Reels 987005-987006), but none appeared to fit the description, though at the time I was looking I had not yet made the connection to “Daniel Cirode” and possibly Daniel White, so I may need to inquire whether there are entries under those names.

Almost all the William Cirode entries concerned real estate, with exception of one to Edward Applegate that concerned “personal property.” There is also no entry for Cirode in the comprehensive index for Jefferson County Wills. I also examined the indices for the Jefferson County Court Order Books from 1834-1854, and found nothing that would be relevant to Wood’s case, which makes more sense now that I know Cirode left for France instead of dying in the United States.56

These below lawsuits involving William Cirode appeared in two places: the on-site database of Jefferson County judicial records at Kentucky Department of Libraries and Archives (these are the the five digit case numbers, and appear to be Common Law suits); and the Jefferson County Chancery Court Defendants Index (microfilm at KDLA).57

- WC vs. Bremaker, Francis, Accession # A2007-022 (These are Common Law cases), Case # 22546, Box # 185, Date 1834

- WC vs. Bremaker, Francis, Accession # A2007-022, Case # 20421, Box # 167, Date 1834

- WC vs. Brindley & Breece, Accession # A2007-022, Case # 22584, Box # 185, Date 1834

- WC vs. Crutchfield, Samuel F. et al., Accession # A2007-022, Case #26317, Box # 213, Date 1837 (Cirode sues to collect around $600 due him and wins the case)

- WC vs. Degaalon, (Degallon) Jane, Accession # A2007-022, Case # 24647, Box #201, Date 1836 (Cirode sued a decree of trespass in replevin, claiming that Degallon had seized valuable bags of coffee and a soap factory, totaling over $2000, that belonged to him; eventually dismissed, with signatures of both parties)

- WC vs. Hawes, Mitchel P., Accession # A2007-022, Case # 29715, Box # 237, Date 1840 (Suit to recover an unpaid debt owed to Cirode by Hawes)

- WC vs. Hyman, Samuel & Henry, Accession # A2007-022, Case # 23502, Box # 193, Date 1837 (Cirode sues Hymans to recover around $575 due him; suit dismissed)

- WC vs. Kinney, George W., et al., Accession # A2007-022, Case #22678, Box #186, date 1839 (Suit by Cirode against several parties for broken covenant and damages totalling $700, filed in 1834; George Kinney had rented a brick house from Cirode in 1832 together with his household property, which is listed in the petition; judgment eventually given in 1839, though unclear for whom)

- WC vs. Maagruder, Tilman & Company, Accession # A2007-022, Case # 29447, Box #235, date 1839 (Cirode sues for debt owed by defendants totalling $1133; defendant claims the debt has been paid, pleadings eventually withdrawn)

- WC vs. Edward Applegate (spelled Cerode), Accession # A2007-022, Case #23993, Box #196, date 1835

- WC etc. vs. James C. Johnston, Case #4648, in Chancery Court Defendants Index for Jefferson County (photographed; contains affidavits showing that Cirode had intentionally moved his slaves out of New Orleans to avoid creditors; that he gave a friend a fraudulent mortgage to secure property in Louisville for his family; and that he was especially concerned to secure property for his daughter; see Johnston v. Cirode.)

- WC etc. vs. Roy Pierre, Case #6511 (July 1849), in Chancery Court Defendants Index for Jefferson County (see Roy v. Cirode for summary)

- WC etc. vs. Aristides Vaible, Case #2645 (September 1840), in Chancery Court Defendants Index for Jefferson County (Suit over a transaction involving rope)

- WC etc. vs. William C. Williams, Case #3766 (September 1842), in Chancery Court Defendants Index for Jefferson County (Suit by Williams alleges that Cirode leased from him a house and has rent due in 1842 that is unpaid; Williams “alleges that said Cirode has moved to New Orleans and is now a non-resident of this commonwealth and absent from the same,” and has removed all of his property from the state, leaving none that Williams can recover under common law, or at least not enough to cover the rent owed, but Cirode does have possession of a house in Louisville purchased from Hyman and now in the possession of Cirode’s agent Didlake, which house Williams petitions to have attached; includes copy of deed between Hyman and Cirode)

- WC etc. vs. William C. Williams etc., Case #4368 (June 1844), in Chancery Court Defendants Index for Jefferson County (Williams is still seeking to recover rent from Cirode, as in 1842; he now “alledges that said Cirode has as he has heard & believes & therefore charges left New Orleans and departed to Europe & to parts unknown and probably to France”; Williams believes that Cirode has no moveable property or slaves in the state and so asks again to have real estate attached; the cause was apparently consolidated together with James C. Johnston’s case against Cirode to recover an even larger debt of nearly $2000; the property is eventually ordered to be sold at auction; Williams further alleges that Cirode has made some “pretended mortgages” to shield his property from creditors)

- Bacon, Edmund, vs. WC, Accession # A2007-022, Case # 25982, Box #211, Date 1838 (Bacon, administrator of a deceased Edmund Bacon, sues Cirode for having detained and refusing to return a certain fourteen-year-old female slave named Caroline, or the equivalent value of $800; Bacon had “casually lost” the slave, and Cirode had claimed her by “finding” despite “well knowing the said slave Caroline to be the property of him the said Bacon”; Cirode denied that he detained the slave, and suit eventually dismissed)

- Hyman, Samuel, vs. WC, Case #2589 (Year 1833), in Chancery Court Defendants Index for Jefferson County

- Hyman, Samuel, vs. WC, Accession # A2007-022, Case #23012, Box #189, Date 1836 (Hyman sues Cirode to recover property that Cirode seized on a distress warrant, similar to Shockley vs. Cirode; dismissed)

- Jones, Roger (a “Free Man of Color”), vs. WC, Accession # A2007-022, Case # 25359, Box #206, Date 1837 (photographed; claim of assault and battery in Common Law court)

- Shockley, James vs. WC, Accession # A2007-022, Case #24285, Box #199, Date 1836 (Replevin dispute between Cirode and Shockley, a pork manufacturer to whom Cirode had rented a portion of his Louisville store and then seized some his property for back rent; Shockley sued to recover the seized property, appears to have won a verdict)

- Ward, David L. (heirs: Sally Grayson, William Ward, William D. Payne, Emeline E. Payne) vs. WC, Accession # A2007-022, Case # 25096, Box # 204, Date 1840 (Suit for ejectment from premises Cirode occupied, first filed in 1836)

- Degallon, Henry (Executrix) vs. Mary Cirode, Case #91, June 1835, in Chancery Court Defendants Index for Jefferson County

On September 8, 1835, the Jefferson County Court appointed “Jane Degallon guardian to Mary Selina Degallon Cirode, infant daughter of Yves Cirode … whereupon she gave bond in the penalty of one thousand dollars with Hugh Ferguson and John A. Honors her securities conditioned according to law.”58

This, combined with the indexed suits above against Mary Cirode and Jane Degallon, again make me think William Cirode was related to Yves Cirode, perhaps the brothers discussed in saugera2011. Perhaps the middle name of William Y. Cirode listed in Cincinnati city directory is inherited from Yves?

I also noted these Robert White lawsuits, in case they are related to the White whom Zebulon Ward claimed actually owned Henrietta Wood:

- Charles (of color) vs. Robert White, Case #916, October 1837, for freedom

- Turner (of color) vs. Robert White, Case #917, October 1837, for freedom

- Willis (of color) vs. Robert White, Case #918, October 1837, for freedom

- Minerva (of color) vs. Robert K. White, Case #3001, May 1841, for freedom

And many other Robert K. White entries in Chancery Court Defendants Index for Jefferson County.

See blaufarb2005, and also the mention of Cirode in French Grant in Alabama. Could this also be the William Cirode who also received a grant of 80 acres of land in Jennings County, Indiana, on April 24, 1820? (Ancestry.com.)↩

Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky Marriages, 1797-1865 (n.p., Genealogical Publishing Company, 1966), 19, excerpt on Google Books.↩

“Leather, Shoes, Boots, &c.,” Frankfort Argus, May 31, 1826, p. 4. An advertisement for Cirode’s Frankfort tanyard (“lately occupied by Wm. Porter”) appeared in the 1823 Frankfort **Commentator*. See December 13, 1823, issue, p. 4, on GenealogyBank.com. See also September 11, 1824, issue, p. 3.↩

“For Sale,” Lexington Reporter, December 10, 1828. The ad appears to have run through November and December.↩

Signed “William Cirode, Lex., August 30th, 1824.” This ran in the Lexington Kentucky Gazette, October 14, 1824, p. 4. Found on GenealogyBank.com.↩

“Tanyard for Sale,” Lexington Reporter, November 5, 1828. Found on GenealogyBank.com. The ad began running in September.↩

Census data from Ancestry.com.↩

G. Collins, *The Louisville Directory for the Year 1838-9 … (Louisville: J. B. Marshall, 1838), 22, examined at Filson Historical Society.↩

See the ad beginning on January 20, 1837, and running through the end of the month; the code in the corner suggests it was purchased on the 19th. An article in the Daily Journal from November 16, 1836, offering a reward to anyone who could help the subscriber track down a man who took his money promising to give it to William Cirode, and then kept the money. That suggests Cirode was still in Louisville late in 1836. All these are available on Newspapers.com, where the Daily Journal is listed by its later name Courier Journal.↩

The ads can be seen on Newspapers.com. G. B. Didlake & Co. had “on hand and for sale—1000 Skirting Hides; 2000 Spanish Hides; Calf and Kip Skins; Padding; Wool; Candles, mould and dipt.”↩

See p. 2 of the October 23, 1839, issue, available on Newspapers.com.↩

See for example, the issues for April 1, April 24, and April 25, 1841, all on page 4, all on Newspapers.com.↩

See, for example, January 3, pg. 1, on Google News, which also says he is a “dealer in hides.”↩

See, for example, January 5, pg. 3 or March 2, pg. 5 on Google News. The ad for sheep skins notes they are “a good article for the northern market.”↩

See, for example, March 16, pg. 2 or February 26, pg. 3. on Google News↩

Notarial Records of J. B. Marks, Vol. 12, Act 3 (4 December 1838), NONA.↩

See, for example, January 1, pg.1 on Google News.↩

See January 1, pg.2 on Google News↩

See January 10, pg. 4 on Google News. For the dissolution, see Notarial Records of J. B. Marks, Vol. 12, Act 58 (5 January 1839), NONA.↩

See, for example, June 29, pg. 1, on Google News.↩

(See, for example, January 22, pg.2 or July 1, pg. 2 on Google News↩

See May 21, pg. 2 on Google News↩

See, for example, July 1, pg. 3 on Google News.↩

In the 1838 and 1841 New Orleans City Directories, Cirode is listed as a “com mt” or “merchant” at 13 Poydras St. and 19 Poydras St., respectively. (The change in number could be a typo, or a slight renumbering.) This is the store that Cirode leased from Shields, Turner & Renshaw (who appear in the 1838 city directory as “Western Produce Merchants” at 15 Poydras and 96 New Levee) in November 1837. He then subleased “part of the building known as the ‘Blue Stores,’ in Poydras Street, in this Parish, having twenty nine feet front on Poydras Street, by the same depth below, and sixteen feet front by the same depth upstairs, embracing two doors on said Poydras Street and adjoining the store now occupied by Messrs. Sheilds, Turner & Renshaw, for and during the term of one year from the date thereof, and ending on the thirty first of January one thousand eight hundred and thirty nine.” (Notarial Records of Joseph B. Marks, Vol. 9, Act 89 (February 1, 1838), NONA. The original lease to Cirode is notarized by Marks on November 28, 1837.)

Shields, Turner & Renshaw subsequently leased to Cirode the store “the store lately occupied by them the said Firm, situate on Poydras Street between Commerce and Ochafitoulas (sp?) streets, and adjoining the store at present occupied by said Cirode, for the term of Two years, commencing on the first day of December next (1838) and ending on the Thirtieth day of November Eighteen Hundred & Forty,” at rate of $1800 per annum. He is barred from subleasing said premises or any part without written consent “except for commercial purposes.” (Notarial Records of J. B. Marks, Vol. 11, Act 169 (30 November 1838), NONA.)

A week later, Cirode annulled the sub-lease with Mullen and then formed a new sub-lease for “a part of the building known as the blue stores at the corner Commerce and Poydras Streets in this city having, First on the lower part of said premises a front of forty two feet on Poydras Street commencing at the corner of said Commerce Street, having three doors opening on Poydras Street and two doors on Commerce Street with the whole depth of the store and Second the upper part of said premises as it is now partitioned off, for and during the full term of two years, which lease commenced on the first day of November last, and expires on the thirty-first day of October eighteen hundred and forty, inclusive.” Mullen rents for $2000 per annum, paid quarterly. (Notarial Records of J. B. Marks, Vol. 12, Acts 10-11 (7 December 1838), NONA.) Cirode later sued Mullen to collect rent: see images from New Orleans Public Library.

The reference to these addresses as the “Blue Stores” is somewhat perplexing, since other sources in the Vieux Carre mention that name in association with a building on Decatur or N. Peters between Bienville and Conti. See “Neglected Decature Square Comes to Life,” Vieux Carre Courier, February 17, 1967, in the Vieux Carré Survey binder at Historical New Orleans Collection. In 1878, the “Blue Stores” appears in an ad for a grocer at the corner of Old Levee and Bienville. An ad in the Daily Picayune on November 2, 1843, mentions “‘Blue Stores’–Triangle Buildings.”

Cirode’s business advertisements in the Commercial Bulletin from January through about November 1839 all give his address as 19 Poydras Street.↩

Cirode advertises “a good two story brick house in St. Joseph Street between Camp and Magazine sts.” for rent consistently July-September 1839.25↩

A William Cirode listed as a merchant shows up on 13 Conde St. in New Orleans in an 1842 city directory. The contemporary address is based on information from Jennifer Navarre at Historic New Orleans Collection, using the Vieux Carré Survey. Based on geocoding he has done with Sanborn fire maps from 1880s, Wright Kennedy thinks 13 Conde St. would be a four-story building on what is now Chartres Street near the intersection with Canal.↩

An ad placed by Cirode in the Commercial Bulletin, August 1, 1843, pg. 3 notes his address is 56 Old Levee. From October 25 until at least November 17, 1843, W. Cirode of 56 Old Levee advertises to rent “the store, or one half of it, between St. Louis and Conti sts.” For example, see November 7, 1843, pg.1 on Google News. The contemporary address information is from Jennifer Navarre at Historic New Orleans Collection, using the Vieux Carré Survey. This may be around the former site of the Importers Bonded Warehouse, built in 1867.↩

The sheriff’s summons in Parish v. Cirode providing Cirode with a copy of Parish’s petition was delivered “at his domicil No. 243 Dauphin Street with his wife residing in said domicil” around January 14, 1843. Cirode places an ad to rent “a two story Brick House, 243 Dauphin, near Main Street, until the 1st of December” from August 4 to at least November 1843 in the Commercial Bulletin. See, for example, August 30, pg. 3 on Google News.

Wright K. says that “Main” probably refers to DuMaine, one block upriver from St. Philip. Records from the Vieux Carre Survey seem to confirm this. An 1819 record concerning present-day 911 Dauphine Street places it “between St. Philip and Main, No. 121.” (See Louisana Courier, June 14, 1819.) An 1855 notarial record for present-day 907 Dauphine Street says that a “two-story house in brick, bearing the No. 245 Dauphine Street, also, a two-story kitchen in brick and other improvements” stood on the property. The street numbers were redone shortly thereafter and present-day 905 Dauphine Street became No. 211 Dauphine. But this evidence suggests that No. 243 would have been somewhere between present-day 901 and 907 Dauphine Street, most likely at present-day 905.

These lots (18829 through 18831) were the site of three two-story brick buildings built in 1833 by Pierre Forestier. (See Stanley Clisby Arthur, Old New Orleans: A History of the Vieux Carré, p. 233.) Each had a detached three-story kitchen. One of these houses may have been the one where Cirode lived.↩

In 1843, his address in the directory (without an occupation) is 339 Burgundy. See email from Wright Kennedy, with images. Jennifer Navarre at New Orleans Historical Collection thinks this might be across Esplanade Ave.↩

Notarial Records of J. B. Marks, Vol. 14, Act 104 (1 August 1839), NONA. This act notarizes sale to Camp. Includes receipt for sale of Caroline, aged 13 or 14, to Cirode from Tilman Magruder & Co., for $550, dated Louisville, March 9, 1837. Also includes a certificate from the Office of Mortgages ensuring that there was no mortgage standing in the name of Cirode and recorded against Caroline. Includes signature of Jane M. Cirode as well, showing that she was in New Orleans by August 1839. The sale is recorded in the Conveyance Records for Orleans Parish, Vol. 25, p. 484, which notes that Camp paid by promissory note.↩

Conveyance Records Books, Orleans Parish, vol. 25, p. 641.↩

An email from Sara Brewer, an archivist at the Atlantic NARA branch where the manifests are held, looked at the Cirode manifests and found that “the January 15, 1840 voyage has an Eliza listed and the March 25, 1840 voyage has a Phillis and Elizabeth listed.” Neither mentions a Henrietta. She also noted, however, that most of these manifests have been scanned and placed on Ancestry.com, so there may be more there.↩

Notarial Records of J. B. Marks, Vol. 16, Act 133 (4 February 1840), NONA. “And now the said Vendor declared that, he acquired said slave from Edward O’Connor in Mobile in the year 1836, with which declaration the present purchaser declares himself satisfied.” See also Conveyance Records Books, Orleans Parish, vol. 27, p. 43, which gives amount of sale as $500.↩

Notarial Records of J. B. Marks, Vol. 21, Act 150 (11 December 1840), NONA, which contains Jane M. Cirode’s signature as well. See also Conveyance Records Books, Orleans Parish, vol. 27, p. 595, which gives the sale price as $700, but spells name as Ripa.↩

Notarial Records of J. B. Marks, Vol. 21, Act 149 (11 December 1840), NONA. For quote and amount, see Conveyance Records Books, Orleans Parish, vol. 27, p. 598.↩

Notarial Records of J. B. Marks, Vol. 32, Act 103 (6 May 1843), NONA. See also Conveyance Records Books, Orleans Parish, vol. 34, p. 138, which describes Margaret as a “negress” and Eliza as “her daughter a griffonne.” The price is listed as $450 cash.↩

See Conveyance Records Book, Orleans Parish, vol. 36, p. 495, the sale was dated September 2, 1844, and gave the price as $385.↩

See issues of the Daily Journal on Newspapers.com.↩

This different version provides book and page number for the record.↩

An email from Sara Brewer, an archivist at the Atlantic NARA branch where the manifests are held, looked at the Cirode manifests and found that “the January 15, 1840 voyage has an Eliza listed and the March 25, 1840 voyage has a Phillis and Elizabeth listed.” Neither mentions a Henrietta. She also noted, however, that most of these manifests have been scanned and placed on Ancestry.com, so there may be more there.↩

From typescript Mobile Directory, 1842, arr. Mrs. John H. Mallon (Mobile: Mrs. Lester E. Taylor, n.d.), p. 7, which I received through ILL at Rice. See Worldcat entry. An individual entry for Robert K. White also appears on “dauphin c commerce” (p. 39).↩

The entries read: “Cirode, Daniel W, clerk at Tribune office, r 95 st michael.” (p. 55) and “White, Robert, city guard, r concepcion b maine & mass’ts.” (p. 113). See Wood, E. T., Mobile directory and register : embracing the names of firms, the individuals composing them and house holders generally within the city limits, … Mobile, 1844. 202pp. Sabin Americana. Gale, Cengage Learning. Fondren Library, Rice University. 05 November 2015.↩

According to testimony in Parish v. Cirode, Cirode thought their failure was due to “depreciation of goods & exchange,” including a discounting of Mobile money. But it seems like he also blamed White. He spoke highly of his son Daniel and said he was going into the commission business.↩

See Ancestry.com U.S. Passport Applications, 1795-1925 database, which includes National Archives and Records Administration (NARA); Washington D.C.; NARA Series: Registers and Indexes for Passport Applications, 1810-1906; Roll #: 2; Volume #: Roll 2 - Index to Passport Applications, 11 May 1843-30 Sep 1846. The passport application also indicates that he had received a naturalization certificate in Louisville on September 17, 1840, around the time his daughter was married.↩

Louisville Daily Courier, January 20, 1851, p. 2, available on Newspapers.com.↩

See “R White, Covington” and “Mrs. R R White & s, Cov,” respectively, in “Arrivals at the Principal Hotels,” Louisville Daily Courier, July 17, 1851, and August 21, 1852, available on Newspapers.com.↩

Kentucky, Kenton County, 1855-1861, Vol. 19, p. 218, R.G. Dun & Co. Credit Report Volumes, Baker Library, Harvard Business School. Thanks to Ryan Shaver for the transcription.↩

See Kenton County Tax Assessment Rolls, Microfilm 008091, Kentucky Department of Libraries and Archives.↩

Post office notices, taxpayer notices, and other articles in in the Daily Picayune in 1850 and 1852, and again in 1868 in the New Orleans Crescent, suggest D. W. Cirode was there at least that long. And an article headlined “Larceny” in the January 10, 1848, New Orleans Daily Picayune (p. 4) says an Elizabeth Croakney was charged with “stealing several articles from the house of D. W. Cirode.” Several articles concern a slave named Jim belonging to “Mr. Cirode” who is accused of burglary on more than one occasion. See the Daily Picayune, October 19, 1848, p. 2; November 1, 1850, p. 2; November 4, 1850, p. 2. An article in the May 29, 1852, issue (p. 2) alleging D. W. Cirode was again a victim of theft places his room “on Poydras St.” Some of the later post office notices expand his name to “Daniel W. Cirode.” See, for example, the August 5, 1852, issue of the Daily Picayune (p. 4). A notice on August 21, 1852, in the Daily Picayune, p. 3, announces the arrival of “Mrs. Cirode, Cin.” at the Louisville Hotel, presumably to visit Daniel. And a “Mrs. M. A. Cirode” has a letter awaiting her in the post office in 1855, according to the April 29, 1855, issue (p. 2); and again in 1857, this time expanded to “Mary A. Cirode” (October 4, 1857, p. 6).↩

Also on this block, according to same directory, was a livery and sale stable named George Brown and Co., as well as a blacksmith named Patrick McCormick located on an alley off the south side of the street. A Mrs. Sarah Armstrong also lived on the northside of the street.↩

Cincinnati City Directories were examined at the Cincinnati History Library and Archives. See also this page from the 1850 Williams directory on Google Books, which lists numerous boarding houses, including one of Mrs. S. Tuttle.↩

The will is in box 11, case number 3780.↩

William Y. Cirode married Adda White in Claiborne, Mississippi in 1859, and this could be the Adelaide W. Cirode found widowed in St. Louis in 1910. W. Y. Cirode of Missouri arrives at the St. Charles Hotel in New Orleans in 1858 (Daily Picayune, February 19, 1858, p. 8). Later appearances of a grocer and cotton factor (interesting that those went together) named Cirode in Memphis in 1865 and after suggest that William Y. Cirode may have relocated there during the Civil War, remaining until at least 1878. His children “Wm. Yeves Cirode and Ada White Cirode” were later baptized there; see Nashville Union and American, October 13, 1870, page 1, on Newspapers.com. Yet he seems to reappear as a resident of Colorado “representing mining interests” in the 1880s. See New Orleans Daily Picayune, January 25, 1882, page 2; February 22, 1882, page 7; Salt Lake Herald, January 19, 1889, page 5. An obituary for William Yeves Cirode, likely the son baptized in Memphis, appeared in the St. Louis Post Dispatch in 1900, and he is apparently buried in Bellefontaine Cemetery.↩

Exception is vol. 23, March-April 1841, which I didn’t look at because there did not appear to be an index available.↩

Christina R. looked through these indices as part of RA Assignments.↩

There is no will listed for Cirode/Cerode/Cirod in the Jefferson County Index to Wills, 1784-1919, at the Kentucky Department of Library and Archives. Other probate settlement records were transferred back to the Jefferson County archives. These are possibly at the Louisville Metro Archives (contact deborahwalker@loukymetro.org), Jefferson County Clerk, or Jefferson Circuit Clerk.↩

Photographs for most of them were taken by Clair in Summer 2016 as part of RA Assignments.↩

Jefferson County Court Order Books, vol. 17 (1835), p. 102, Kentucky Department of Libraries and Archives.↩