Kate Stone

Drawing from Photograph, in Frontispiece of stone1995

Author of a journal published as stone1995. For more information, see the LSU Press book description:

Kate Stone was twenty when the war began, living with her widowed mother, five brothers, and younger sister at Brokenburn, their plantation home in northeastern Louisiana. When Grant moved against Vicksburg, the family fled before the invading armies, eventually found refuge in Texas, and finally returned to a devastated home.

The family members who are mentioned most often in her journal include:

- “Mamma” (Amanda Stone), widow of William Patrick Stone. According to menn1964, Stone (who was 36 years old in 1860) was the owner of 77 slaves in 1860.

- “My Brother” (William R. Stone), Kate’s brother. He enlisted at Vicksburg in May 1861, was wounded twice (including at Antietam), returned home on January 1, 1863 with an injury suffered at Fredericksburg, and was paroled in 1865.

- “Jimmy” (James A. Stone), another of Kate’s brothers, aged 14 in 1861.

- “Johnny” (John B. Stone), another brother, aged 13 in 1861.

- “Lt. Holmes” (Henry Bry Holmes), Kate’s future husband, whom she married in 1869.

Most of the notes here are focused on the movements of Kate’s family and their enslaved people in the months before and after the fall of Vicksburg.

1862

From her home at Brokenburn, Kate reported on the latest news from Vicksburg and entered occasional sharp jabs about Benjamin Butler’s proclamations in New Orleans (see pp. 105, 111, 125), but for the most part the entries convey a sense of waiting and watching, with the usual rounds of social visits, sewing work, outings to church or fish, and records of what she is reading.1

Few planters in her neighborhood left the area in the months after New Orleans fell, with a few exceptions.2 But Kate’s first sight of “Yankee gunboats descending the river” occurred on June 25 (p. 122), and soon thereafter rumors reached the Stones about the impressment of slaves to work on the canals around Vicksburg, prompting Amanda Stone to call “all the men on the place” and tell them to run and hide “if the Yankees came on the place.”3

For the moment, Stone believed that the family’s enslaved men would obey this order, but that confidence did not last long. Only a few days later, Stone reported that “the Yankees have taken the Negroes off all the places below Omega, the Negroes generally going most willingly, being promised their freedom by the vandals” (p. 127). These actions prompted a new wave of planters to leave the river or send “their Negroes to the back country. We hope to have ours in a place of greater safety by tomorrow” (June 30, p. 127).4 A few days later, no movement had taken place, but as further reports of Union impressment raids from Lake Providence to Pecan Grove, and from Omega to Baton Rouge, filtered in, Amanda Stone resolved to “have the Negro men taken to the back country tomorrow, if she can get them to go. Generally when told to run away from the soldiers, they go right to them and I cannot say I blame them” (July 5, p. 128).5

In early August, the appearance of a large fleet of Union gunboats at Milliken’s Bend led Stone’s mother to send off “the Negro men with Jimmy to take care of them to Bayou Macon,” but as soon as fears of an imminent landing passed, “she sends for them again” (Aug. 19, p. 137).6 The Stones at this point were not the only planters considering a move: “the planters generally are moving back to the hills as fast as possible,” Stone noted on August 25, and “there are two families refugeeing in our neighborhood” (138-139). James G. Carson had also “gone to look for a place for himself,” and Amanda Stone “asked him to notice for one suitable for her” (Aug. 25, p. 139). A few days later, Mrs. Carson was preparing to leave, but by September 30 she had apparently returned (p. 145).

Much of the immediate sense of danger had passed by October, when Stone reported that new overseers had been hired (first Mr. Blakely, then Mr. Ellison) to oversee the Stones’ slaves as they began “housing the potatoes and goober peas [peanuts] and priming the sugar cane” (Oct. 29, p. 152). Jimmy, meanwhile, had been dispatched to Mississippi to buy leather to make winter shoes for the Stones’ slaves. But plans were put in place to remove inland if necessary: “Mamma has rented a place on Joe’s Bayou above overflow from a Mr. Storey. Can send the Negroes there if the Yankees come again” (Dec. 12, 162-163). When a force of Union soldiers did march to Delhi later that month on Christmas, “the overseer carried most of the Negroes back to the Joe’s Bayou. But as they did not come, the Negroes were brought back in a pouring rain disgusted with their Christmas outing” (Dec. 29, p. 165).

1863

As the new year opened, news of Grant’s more determined movements against Vicksburg prompted more serious plans to leave the river. Stone’s brother William, who had returned with a battle injury on January 1, left on January 25 “with the best and strongest of the Negroes to look for a place west of the Ouachita,” leaving “only the old and sickly with the house servants” behind (p. 168-169). “My Brother” was determined that the family should leave, wrote Stone, “and we will commence packing tomorrow. The Negroes did so hate to go and so do we” (p. 169). The next day, Stone wrote one of her briefest entries to date:

Jan. 26: Preparing to run from the Yankees, I commit my book to the bottom of a packing box with only a slight chance of seeing it again.

A little over one month later, however, on March 2, Stone resumed her journal, reporting that “the Yankees have not visited us yet, and so after more than a month’s concealment I take my book out to write again.” Although Union soldiers had been all around the place, and the Stones had been “expecting them all the time and preparing to start for the hills beyond the Macon, the Mecca for most of the refugeeing planters,” put they did not come (p. 169).

Slaves at Salt Works

William Stone had, however, been gone the entire month with the male slaves he carried off on January 25. Having first “left the Negroes” at Delhi “until they could be shipped on the train,” “Brother” eventually took “the Negro men to the salt works [near Winnfield, La.] away beyond Monroe and put them to work” (March 2, p. 170). After Jimmy returned from there, Amanda Stone “sent out the overseer, Mr. Ellsworth” (p. 170).

March: Jane’s Flight

At home, struggles between the Stones and enslaved people left behind intensified or became more visible to Kate around the same time. For example, “a terrible row” occurred between “Jane, Aunt Laura’s cook, and Aunt Lucy,” another enslaved woman, in which Jane hit Lucy with a chair, injuring her. “Mamma had Jane called up to interview her on the subject, and she came with a big carving knife in her hand and fire in her eyes. She scared me,” confessed Kate (Mar 2., p. 170-171). Because “Jane showed a very surly, aggressive temper with Mamma,” Amanda Stone did not say much, but later that night, Jane left with her two children and another enslaved man from a different plantation and “started for the camp at DeSoto.” She was spotted on the way waiting to be ferried across the river, together with “fifty others,” prompting Stone to observe that “all the Negroes are running away now, and there are numbers of them” (p. 171).

According to Stone, the night that Jane left was a “scene of terror,” with all the quarreling, Lucy’s injury, “Jane’s fiery looks and speeches,” the pursuit of her by Johnny and Uncle Bob, “and then just as we had all quieted down, the cry of fire” in the loom room, which the Stones initially suspected had been set by a vengeful Jane. “We would not have been surprised to have her slip up and stick any of us in the back” (p. 171), and Stone began to carry a pistol that she later discovered was unloaded. Although Amanda Stone initially planned to send for Jane near the levee where she was supposed to still be waiting for river transport, “Aunt Laura implored her not to,” and Stone commented that “I think everybody on the place was thankful to get rid of her. The Negroes dreaded her as much as the white folks. They thought her a hoodoo woman” (p. 172).

Meanwhile, Stone reported that “a great number of Negroes have gone to the Yankees from this section” (p. 173), including 75 from one plantation in one night and 160 from another, even though there were reports of “black measles” among the “negroes at work on the canal” (p. 173). Jayhawker bands in the area had also been active, “taking all the Negroes and all kinds of stock” from several neighboring plantations: “The Negro women marched off in their mistresses’ dresses” (March 4, p. 175).

But meanwhile, the Stones’ enslaved people remained “at the salt works,” where Jimmy had also been for some time. And the Stones still in Carroll Parish continued to wonder when and if Grant’s army would actually attack Vicksburg, straining their eyes each night by looking from the gallery “in the direction they will come” (March 15, p. 179). “So far our Negroes have shown no disposition to leave,” Stone averred on March 15, “but may at any minute” (p. 179). At the nearby plantations of the Hardisons, half a dozen men with their children:

walked off in broad daylight after a terrible row, using the most abusive language to Mrs. Hardison. Mr. Hardison expected to get home today and move them all to Monroe, but he has waited too long. The other Negroes declare they are free and will leave as soon as they get ready. Mrs. Hardison sent for Johnny and Mr. McPherson early this morning. Johnny went at once but they could do nothing (p. 183).

All of this prompted Stone to confess that “this country is in a deplorable state”:

The outrages of the Yankees and Negroes are enough to frighten one to death. The sword of Damocles in a hundred forms is suspended over us, and there is no escape. The water hems us in. The Negroes on Mrs. Stevens’, Mr. Conley’s, Mr. Catlin’s, and Mr. Evans’ places ran off to camp and returned with squads of soldiers and wagons and moved off every portable thing—furniture, provisions, etc., etc. A great many of the Negroes camped at Lake Providence have been armed by the officers, and they are a dreadful menace to the few remaining citizens. The country seems possessed by demons, black and white" (p. 184).

March-April: Stones’ Flight

Not long after these lines, Stone and her family finally departed from Caroll Parish, stopping for two weeks at the plantation of James G. Carson in Anchorage, where Carson himself was busy “in all the hurry and bustle of moving not only his own family but several hundred Negroes, his own and those belonging to the large Bailey estate, for which he is executor” (April 15, p. 188). On April 21, three weeks after departing home, Stone arrived in Monroe, after a brief stay at the home of a Col. Templeton and a passage through Delhi. Her party consisted of seven family members (Mamma, Aunt Laura, Sister, Beverly, I, and the two boys) along with “an assorted cargo of corn, bacon, hams, Negroes, their baggage, dogs and cats, two or three men, and our scant baggage,” including one slave who “was sick, groaning most of the way” (April 21, p. 191).

At Delhi, Stone described a scene that “beggars description” and also swapped stories with “refugees—men, women, and children—everybody and everything trying to get on the cars, all fleeing from the Yankees or worse still, the Negroes” (191). All the refugees had “tales to tell of … their hairbreadth escapes” and were “eager to tell their own stories of hardship and contrivance, and everybody sympathized with everybody else” (191). According to Stone, “nearly all are bound for Texas” (191), and she rode with many other refugees on the railroad from Delhi to Monroe, where they paused at the plantation of a Mr. Deane near Trenton in order to allow “Mamma and Jimmy” to return to Delhi to get a party of soldiers to travel back to Brokenburn “and bring out the Negroes left there. All our and Aunt Laura’s house servants, the most valuable we own, were left” (p. 192).

What Stone heard of their behavior startled her:

We hear that the Negroes [about thirty, according to p. 203] are still on the place, but the furniture and all movables have been carried out to camp by the Yankees. The Negroes quarreled over the division of our clothes … Our beds are all in the quarters. Webster, our most trusted servant, claims the plantation as his own and is renowned as the greatest villain in the country (p. 192-193).

While waiting to hear whether Jimmy would be successful, Stone also received word of the fall of Avery Island to Union forces who were marching on Alexandria, threatening “the salt works on this side where all our Negroes are. Then, what will become of us? We will be absolutely destitute” (April 24, p. 194). She also noted that “this country is filled with refugees” bound for Texas (p. 194).

While at Trenton, Stone also recounted her flight, which had been prompted after a visit to the Hardisons’ place on March 26: “Looking out of the window, we saw three fiendish-looking, black Negroes” who came into the house armed, “cursing and laughing, and breaking things open” and calling each other “Captain” and “Lieutenant.” One eventually “came bursting into our room, a big black wretch, with the most insolent swagger, talking all the time in a most insolent manner,” waving a “cocked pistol” around, and (according to Stone) threatning to shoot the Hardisons’ baby before turning away and laughing. Eventually he came to where Stone was sitting with her “Little Sister” and stood on the hem of her dress, “gesticulating and snapping his pistol. … I was never so frightened in my life” (April 25, pp. 195-196). Stone remained in the room as the men ranged through the house for two hours before lighting matches and leaving.

The next day, back at home, the Stones watched as the Hardisons’ place was totally ransacked by “the Negroes from all the inhabited places around,” which convinced Amanda Stone “to leave, though at the sacrifice of everything we owned” (p. 197). As they packed, “all the servants behaved well enough except Webster, but you could see it was only because they knew we would soon be gone. We were only on sufferance” (p. 198).

April-May: Near Monroe

Stone broke off this narrative on April 26 to report on news from Johnny, who “came back yesterday from the salt works. Affairs are progressing favorably there” (p. 200), but she then resumed her narrative of the flight, writing of a tremendous thunderstorm at the Carsons’ once they arrived there: “Aunt Laura and Mamma said they were worse frightened by the storm than they had been by anything else. They had not had a brutal Negro man standing on their dress and fingering a pistol a few inches from their heads” (p. 202).

By May 2, the Stones—still waiting near Monroe to hear from Jimmy—had moved to stay with the family of Sarah Wadley, but had also received bad news from the salt works: “Jeffrey is dead and several others are very sick. The three whose wives are on the river ran away but were caught. Mamma and Johnny with a new overseer and his wife started to the salt works yesterday. She will start all the Negroes who are able to travel at once to Texas” (p. 204). About a week later, however, “Mamma” returned with bad news from the salt works: “Frank, my maid, and Dan both died of pneumonia and neglect, and three others are very ill,” and the overseer (Mr. Smith) had been unable to start for Texas. “Mamma” had left immediately for Delhi after her return “to make another attempt to have the Negroes brought out, if she can get the soldiers to go with Jimmy,” who had been unable to act earlier because of high water (May 20, p. 207).

Finally, around May 22, Jimmy and Mamma “returned in triumph with all the Negroes except Webster, who had joined the Federal Army some time ago, and four old Negroes who were left on the place to protect it as far as possible” (p. 208-209). According to Stone, there were skirmishes between Jimmy and “a body of forty Yankees” who fired on them as they escaped. And she also makes clear that Jimmy had to use force to capture those who were “refugeed”:

Jimmy and the men with him hid all day in the canebrake just back of the fence and in the fodder loft at Brokenburn and stole out at night to reconnoiter. They found what cabins the Negroes were in, and while hiding under Lucy’s house they saw her sitting there with Maria before a most comfortable fire drinking the most fragrant coffee. They were abusing Momma, calling her “that Woman” and talking exultantly of capering around in her clothes and taking her place as mistress and heaping scorn on her. … At daylight they surrounded the cabins, calling the Negroes out and telling them it was useless to resist. They were captured. (209)

These slaves immediately left with Jimmy for Texas, rushing to join up with “Mr. Smith’s train,” which by then had left the salt works. The Stone women, meanwhile, remained and waited at the Wadleys’ near Monroe, where “the country is crowded with refugees, every house full to overflowing” (May 26, p. 215), as all waited to hear what was happening at Vicksburg. Stone filled her time with “visiting and visitors, blackberry parties, and long walks over the hills” (p. 219). But, fearing that they were outstaying their welcome at the Wadleys’, and also motivated by news that a “mongrel crew of white and black Yankees” had defeated Confederates at Milliken’s Bend, the Stones resolved to leave for Texas soon (p. 218).7

June-July: En Route to Texas

While preparing to depart for Texas in June, Stone received a letter from brother Jimmy in “Titus” County, Texas, that painted a discouraging picture: “the country is not more abundant than this and Billy, another Negro man, is almost dead” (220).8 But Amanda “hopes to find it better than Jimmy paints it,” and around June 19, the Stones departed Monroe: “We are on the road for Texas at last” (June 19, p. 220).

The party arrived in Lamar County, Texas, on July 7, after a “tiresome, monotonous trip of little less than three weeks, and I am already as disgusted as I expected to be” (July 7, p. 223).

For a timetable of Stone’s trip, see Google Doc.

Hiring Out

Once Mamma, Stone, and “Mr. Smith” arrived in Lamar County, staying about twenty-five miles from Paris, the slaves were hired out: “Mr. Smith is hiring most of the hands out for the balance of the year. There is a great demand for them, and he can see that they are well taken care of. They have all gotten perfectly well since coming out here” (226).9 But in July, she also mentions that “Jimmy” traveled to Navasota “with only the Negroes” in order “to buy salt and different kinds of merchandise” (228).

Stone’s mother remained concerned, however, about what her enslaved people would do.10 On Stepember 1, Stone recorded that “Mamma” was anxious for Jimmy to return from Navasota: “she wants the wagons to move the Negroes before they hear that the Yankees are coming in from the North, as it is rumored, and before they have a chance to make a break for the Federal lines again” (239).11

On Texas

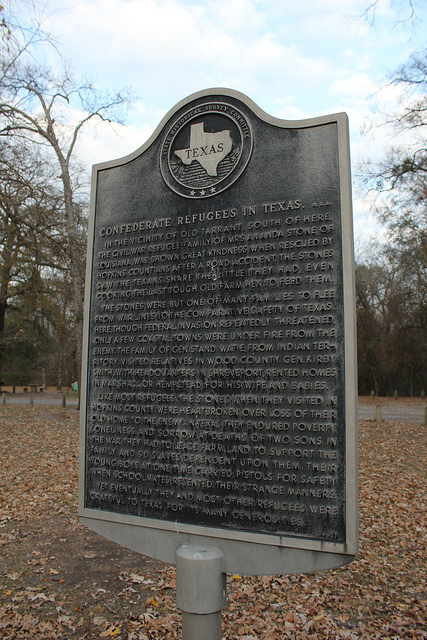

Photo of Texas Historic Marker about Stone’s Family, taken by Nicolas Henderson, Flickr user TexasExplorer98. See text.

Stone was reluctant to go to Texas from the beginning:

How I dread being secluded on some remote farm in Texas, far away from all we know and love and unable to get news of any kind. It is a terrifying prospect. (214)

She was not any more impressed once she arrived “in a dark corner of the far off County of Lamar after a tiresome, monotonous trip of little less than three weeks, and I am already as disgusted as I expected to be” (223), partly because she believed Union feeling was rife in the area, but also because “there must be something in the air of Texas fatal to beauty. We have not seen a good-looking or educated person since we entered the state” (224).

Stone also detected a general animosity towards refugees:

The more we see of the people, the less we like them, and every refugee we have seen feels the same way. They call us all renegades in Tyler. It is strange the prejudice that exists all through the state against refugees. We think it is envy, just pure envy. The refugees are a nicer and more refined people than most of those they meet, and they see and resent the difference. That is the way we flatter ourselves. (238)

Despite her dissatisfaction with Texas, however, Stone considered herself lucky in comparison to other planters who had not managed to “save” their slaves. “We seem to have almost nothing but servants, and yet we are comfortable, comparatively so” (p. 244).

Stone removed to Tyler (which she dubbed “Refugee Ranch” in October, hoping to soon be joined their by Mrs. Savage, who was also in Texas (p. 249). “There are so many refugees here that we may like Tyler after awhile,” she later remarked (p. 255).12

Stone was not, even so, happy with Texas. But “we certainly have plenty of servants to do our bidding, most of Mamma’s house servants and all Mrs. Carson’s, and that is about all we do have” (p. 258).

1865

Premonitions of defeat began to fill Stone’s entries in the spring, just as the Stones were preparing to move to a new house in Tyler. The bad news from the front made Stone’s mother worry about being able to pay rent: “If the Negroes are freed, we will have no income whatever, and what will we do?” (p. 335)

In May, only days after hearing rumors of Lee’s surrender, Stone learned from “Jessy,” who “came down from the place” in Lamar County that “Hoccles is dead. Everything else is progressing satisfactorily” (p. 337).13 The same month, Stone had moved to their new home and commented on “how comfortably our move was accomplished. Mamma gave general orders to the Corps d’Afrique to move all our ‘duds’ to the new house. We have only the bare necessaries except servants. They are plentiful” (p. 337-338).

After the war, Stone remained in Texas until the fall of 1865. In September, she left Tyler for “Vexation,” her nickname for the farm in Lamar County where most of the Stones’ now freed slaves had been living.

We found nearly all the Negroes in a state of insubordination, insolent and refusing to work. Mamma had a good deal of trouble with them for a few days. Now they have quieted down and most of those who left have returned, and they are doing as well as “freedmen” ever will, I suppose. We were really afraid to stay on the place for the first two days (p. 362).

On October 10, Stone was still at “Vexation,” lamenting her family’s situation: “our future is appalling—no money, no credit, heavily in debt, and an overflowed place” (362). She also complains further about “the Negroes”:

The countrabands are all crazy to return to Louisiana, as soon as they realized that My Brother did not wish to take them and are on their best behavior. What a treacherous race they are! I doubt whether one will remain with us a week after we return … It seems an ill-advised move to take the Negroes back unless they could be bound by some contract to remain on the place, and that is impossible. It is so expensive and troublesome to move about eighty or ninety Negroes such a distance. Two families are to remain. Warren’s is one (p. 363).

There are frequent references to visits at or by Dr. James G. Carson and family, indicating a longstanding relationship prior to their flight to Texas.↩

One was Mrs. Savage, who was “at last persuaded … to leave the river and go out to Bayou Macon until the war is over, for fear of the Yankees raiding the places when they come down the river” (June 11, p. 119). But within a month, Savage had apparently returned with “Negroes, furniture, piano, everything” (131). Only a few weeks later, however, Savage resolved again to return to Bayou Macon, prompting “four of her Negroes” to run away “rather than be moved back” (Aug. 19, p. 138). She was back again, however, by September 30: “she says now she will stay till driven off by Yankees or overflow” (p. 145).↩

See winters1963 for more on this.↩

Among those planters who were said to have already left for Texas “with the best of their hands” were Dr. Nutt and Mr. Mallett.↩

Several weeks later, Stone confessed that while many slaves could be seen returning from work on the canals around Vicksburg, “preferring the old allegiance to the new,” many more were “still running to the gunboats. We would not be surprised to hear that all of ours have left in a body any day” (July 24, pp. 134-135).↩

On the next page, Stone remarks that “The Negroes enjoyed their hasty trip to Bayou Macon. It will give them something to talk of for a long time.”↩

Stone confesses several times that she could not credit reports of black soldiers fighting bravely at Milliken’s Bend: “There must be some mistake” (p. 218).↩

A later entry reports that Billy had died, “the seventh of our Negroes to die since New Year’s” (224).↩

One enslaved woman named “Morine” was hired nearby as a house servant. See p. 235. Stone returned to the demand for hired out servants in a September 19 entry: “We have had a succession of callers recently. The unadulterated natives are all eager to hire Negroes. There is a furor for them. All the old ladies in the country are falling sick just to get their ‘Old Men’ to hire a servant. Who can blame them after their years of grinding toil for seeking a little rest?” (242).↩

One of the slaves who was hired out, a Morine, was seen “sitting at the table with the white folks. She will be ruined by such people” (p. 235).↩

Jimmy returned on September 11, after which everyone was planning to remove to Tyler to live with the widow of James G. Carson, but the conscription of overseer Mr. Smith delayed them. See p. 241.↩

See also p. 266: “Texas will not seem so desolate with old friends around us.”↩

A note on p. 314 indicates that Hoccles and his wife had actually returned to Brokenburn at some point and then come back.↩