Avery Island

Also called the “Island of Petite Anse,” or “Salt Island,” this salt dome rock was named after the Avery Family that settled and mined it in the 1830s. The huge deposit of rock salt here was discovered during the Civil War, used to supply Confederate civilians and soldiers for about a year, and then was captured by Union forces.1

Discovery of the Dome

According to an 1898 account, the salt mine was well-known in the early nineteenth century but not significantly mined for commercial purposes “until 1861, when the price of salt was $11.00 a barrel in New Orleans. In December of that year John Avery, a brother of Capt. Avery, and then a youth of seventeen, asked his father to allow him to repair the old kettles and begin again the manufacture of salt” through evaporation. Avery made about ten barrels a day and sold it locally for $9 a piece, but demand soon exceeded his supply. One day, while digging a new well, an enslaved man named “Bill Odell, who had been one of the original slaves brought by Mr. Marsh from New Jersey, and who lived until about 1892,” hit upon a much larger rock salt deposit just under the surface.2 One later account dates this discovery exactly to May 4, 1862.3

By August 1862, the family had begun exploring serious Salt Works production, as indicated by a letter from Louisiana Governor Thomas O. Moore to Daniel Dudley Avery, who had apparently written to request powder for his “salt operations.” Moore confessed difficulty in procuring the powder because it was being used so often for ordnance. “Although to the public & country generally it would render as great a benefit as used in battle,” said Moore, “as those who use it in that way, must have the material to cure the provisions they eat,” that did not make powder easier to come by.4

Moore did however impress upon Avery that he believed the family was “losing a big fortune” by not pursuing the salt production even more vigorously: “I never saw an opportunity for rapidly making money in my life, I was astonished at the resources for doing so [when he recently visited the Avery Island], & to see the great caution exercised by its proprietor at the same time.”5 Avery apparently worried about producing too much salt and having it waste on hand, but Moore was confident that any salt made “today” could be sold “tomorrow,” and any “hands” hired could be rented by the day or the month and discharged when no longer required. Moore continued:

I think when you make one dollar, you ought to make twenty, without difficulty, but I have come to the conclusion that Judge Avery was not an avaricious man, that he was certain of sure & small profits, & satisfied. But when he can be as certain with big profits, why not be so? Your location with 12 months war, ought to give you a million of dollars, should your rock salt hold out & the supply of water continue as I suppose.6

The extent to which Avery acted on this advice is unclear. But on September 10, 1862, John M. Avery received an exemption from military service to superintend the salt mines on the island.7 And at around the same time, Confederate agents began arriving at Avery Island, too.

Sometime in this same year, the state geologist of Mississippi, Eugene W. Hilgard, preformed an analysis on the salt from Petite Anse Island and discovered that it was 99.880% Chloride Sodium—virtually pure rock salt, with only traces of calcium and sulphate, increasing the renown of the salt island.8

Wartime Production

The state and Confederate governments took an early interest in the salt deposit, as shown by Governor Moore’s letters to Avery and by the rapid arrival of troops to oversee production. R. LaMar Sprigg, of the Confederate mining bureau, visited the Island from Little Rock, Arkansas, on September 4, 1862, and Confederate General Richard Taylor visited on September 8.9

Taylor recalled the visit later, writing in his memoir that “many negroes” were immediately put to work mining the rock for military use:

The want of salt was severely felt in the Confederacy, our only considerable source of supply being in southwestern Virginia, whence there were limited facilities for distribution. Judge Avery began to boil salt for neighbors, and, desiring to increase the flow of brine by deepening his wells, came unexpectedly upon a bed of pure rock salt, which proved to be of immense extent. Intelligence of this reached me at New Iberia, and induced me to visit the island. The salt was from fifteen to twenty feet below the surface, and the overlying soil was soft and friable. Devoted to our cause, Judge Avery placed his mine at my disposition for the use of the Government. Many negroes were assembled to get out salt, and a packing establishment was organized at New Iberia to cure beef. During succeeding months large quantities of salt, salt beef, sugar, and molasses were transported by steamers to Vicksburg, Port Hudson, and other points east of the Mississippi. Two companies of infantry and a section of artillery were posted on the island to preserve order among the workmen, and secure it against a sudden raid of the enemy …10

According to Kneedler’s 1898 account, a special agent from the Confederate government, named Major Broadwell, also came to the island to contract with D. D. Avery to supply the army with salt.11 Other agreements were also made with Alabama, Georgia, and Mississippi. “A scene of great activity ensued. Many hundreds of men were at work, and at times as many as 500 wagons loaded with the product left the island in a day. Some of these ox-drawn wagons made long trips into Texas and northward, while a great deal of salt was hauled to the Atchafalaya river, thence shipped to Vicksburg by boat and from there distributed by rail. So great was the rush that all else on the island was abandoned.”12 A small “plank road, crossing the Bayou Petit Anse and the marshes to the north for nearly two miles, and continuing as a prairie-road to New Iberia,” was also built during the war to accommodate wagon trains; and even before it was completed, some locals including Ben Prescott and Col. Offut were contemplating the possibility of transporting salt up the Red River from the Island and selling it at a profit.13

Contemporary evidence confirms these accounts. In October 1862, a family correspondent reported to D. D. Avery on “a vigorous working of the mines by the agents of the government,” and hoped “that the public may realize an ample supply, by this beautiful provision of Providence, so indispensible [sic] an article.”14 The following month, General Richard Taylor reported to a superior about one of the steamers laden with salt leaving from the island, and also commented on the mine’s “importance to us.” He feared, however, that “if the enemy sense any very considerable force against the salt mines my force would be inadequate to its defense.”15

At this early date, salt seems to have been obtained by using gun powder to blow open large pits, exposing the salt at a depth of around 19 or 20 feet.16 In what appears to be a February 1863 letter from D. D. Avery to John M. Avery, the former instructs the latter to “let my hands have powder enough to blast” more salt from the mine.17

Even using this crude method, however, the island produced 22 million pounds of salt in eleven months, according to a statement from Judge Avery immediately after the war. “From four to six hundred men are said to have been working, day and night, in mining, barreling, and loading the salt in wagons. From one to five hundred teams are reported to have been at one time on the island, coming from every Southern State, and waiting for a supply. The various pits were worked by the owners, the government, and contractors,” producing salt at an average price of 4.5 cents per pound.18 According to kerby1972, there were also 500 slaves working at the salt works “within weeks” of its discovery.

News of the new supply of salt spread quickly to Texas, where newspaper reports corroborated later claims that the salt dome had remained undiscovered until 1862.19 A Houston newspaper during the war enthused that the salt rock would be “large enough to supply the world.”20

Capture

Union interest in the salt island also developed very early on, and in November 1862 gun boats threatened Petit Anse via Vermillion Bay, which reportedly “caused a general stampede from the place.”21 The next month, a correspondent for the New York Times reported to Northern audiences about the “immense value of this mine of wealth” and “mineral wonder.”

Then, on April 16-17, 1863, an expedition led by Nathaniel P. Banks and Godfrey Weitzel successfully captured the island and destroyed the works either that day or a few days after.22 According to a report by Brig. Gen. Cuvier Grover, commanding Fouth Division, the attack was carried out by Col. William K. Kimball with the Twelfth Maine, Forty-first Massachusetts, and one company of the Twenty-Fourth Connecticut Volunteers:

Colonel Kimball destroyed the buildings, 18 in number, their steam-engines, windlasses, boiling and mining implements, and 600 barrels of salt prepared for shipment, blew up their magazine, and brought back to New Iberia about one ton of powder and one ton of nails. Colonel Kimball then returned, having fully executed his orders, and rejoined the division, without loss or casualties, on the 18th, at Vermillion River.

Kimball’s own report verified these details, specifying that the buildings destroyed were ones connected with the salt works.23 It is possible, however, that the destruction of the salt works may have been emphasized to commanding officers who were trying to deflect attention from a missed opportunity to cut off the retreat of Taylor’s army and from some discipline breakdowns during the march to Franklin.24 Another postwar account explained that destroying the salt works would not have taken much, given the rudimentary instruments that were in use at the time: “The works required for [the salt’s] extraction are, however, very simply, for the deposit lies close to the surface, and has only to be quarried in blocks of convenient size.”25

Return to Confederate Control

The Union campaign against the works disrupted production, but June 1864 there is evidence of a slow return to work on the plantation and on the salt mine by a small number of slaves remaining. In 1864, Dudley Avery (who was then in the army) appealed to General R. Taylor to excuse the plantation overseer Mr. [Joseph P.] Kearney from military service, explaining that his father was in Texas and “Mr. Kearney is the only white person remaining on the plantation and has been supplying the people in the adjoining Parishes with salt,” as well as overseeing “thirty working hands, still remaining on the Plantation.”26

And on September 16, 1864, Governor Moore again wrote to Daniel D. Avery to introduce Major John M. Sandridge (sp?), the Chief of Ordnance, to make arrangements to work the Island’s salt mines in order to make up the “scarcity of salt in South La.” The governor confessed that depreciated currency meant that no arrangement could be as fully remunerative to Avery as he would have liked, but he appealed “to your generosity & patriotism rather than to your interest & beseech you to rescue our fellow citizens from distress.”27

For more on efforts by friends and business associates to persuade Avery to boost salt production after his return from exile, see the Avery Family entry.

Postbellum Years

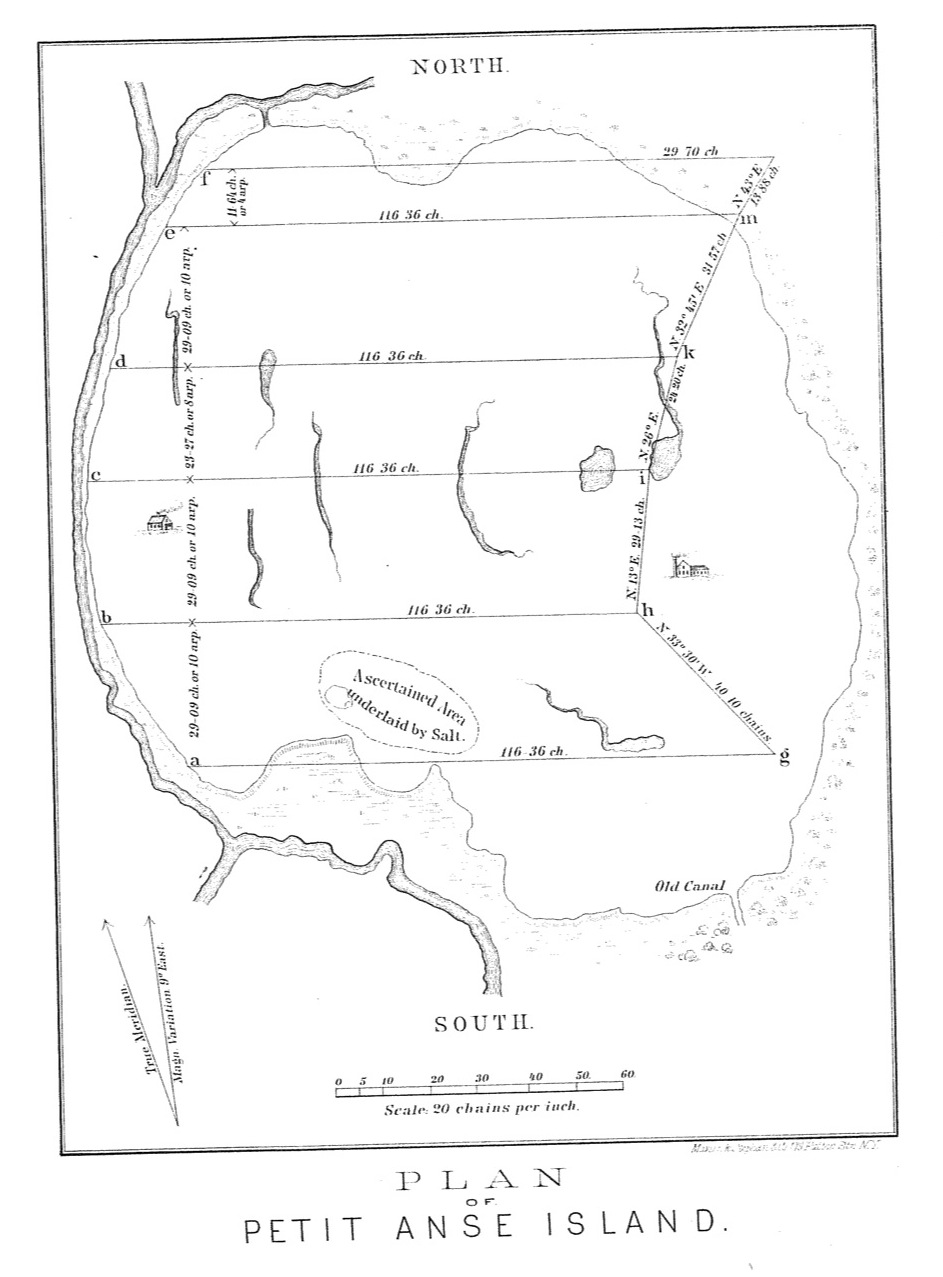

Plan of Petit Anse Island, from an 1867 report by the American Bureau of Mines

One of the earliest commercial interests on the island appears to have been the Louisiana Rock Salt Company, which is mentioned in an 1867 geological report by the American Bureau of Mines. The Bureau praised the potential of the deposit and advised that “well-constructed shafts, and protected galleries in the salt itself,” be built to facilitate commercial mining and reverse the current practice of “working the upper levels first” with salt-pits.28 At least one shaft had already been opened by the Company by the time this report was made. The report also mentioned that “five miners’ dwellings” already existed near the pits that had been opened during the war, and advised that a mill be constructed on site in order to ship ground salt directly from the island. In total, the report estimated that “an eventual expenditure of $250,000” of startup capital would be needed to put its plan into execution.29

How salt would be transported from Petit Anse to market was still an open question at the very end of the war; the Bureau of Mines report recommended that the Louisiana Rock Salt Company dredge the bayou for barge transportation in the first year, but predicted that the Opelousas Railroad would soon be connected to New Iberia, which would become a junction between “the New Orleans, Opelousas, and G. W. road. New Iberia may then, without difficulty, become a centre for the packing business, consuming the cattle of Texas and the salt of Petit Anse.” The report added, in a footnote, that among the advantages of connection to New Iberia would be access to cheap labor: wages for white male labor in New Iberia were then around $25 to $30 per month, with “colored male labor” at “$10 to $15 per month, ‘and found’—an item amounting to almost $150 annually.”30 Whatever the means of transportation, however, the report predicted that the salt at Petit Anse could easily compete with English imports because of the lower cost of home production and the protection of tariffs.

Two years later, parts of this original plan had come to fruition. Two men named Choteau & Price had leased the salt dome under the name of the Louisiana Rock Salt Company and were preparing salt for market, transporting it by steamers to Brashear City and then by rail to New Orleans.31 A merchant firm named Price, Hine & Tupper in New Orleans were serving as the company’s agents and touting the quality of the salt for packing.32

In an 1870 article, the New Iberia Sugar Bowl reported that a reservoir had been sunk that allowed surface water to be pumped out of the mine:

A shaft was sunk eighty feet deep, and galleries commenced, running east and west, and the salt hoisted by machinery in buckets when it was ground, sacked and shipped to market on steamers that came around Vermillion Bay, and ran up through Bayou Petite Anse to the island. Experienced miners were employed, who found it very clean, but quite difficult work, as the rock of salt appears to be seamless, and has to be drilled and blasted with powder. When we last visited the island, we descended into the mine, to a depth of eithy feet, where we found the two galleries combined, made an underground passage three hundred feet in length. …33

Production continued and grew more complex in later decades, as evidenced by several magazine profiles of the island near the end of the century. E.g., According to Warner, “The Acadian Land” (1887), p. 347–9:

In a depression is the famous salt-mine, unique in quality and situation in the world. Here is grown and put up the Tobasco pepper. … The ascertained area of the mine is several acres; the depth of the deposit is unknown. The first shaft was sunk a hundred feet; below this a shaft of seventy feet fails to find any limit to the salt. The excavation is already large. Descending, the visitor enters vast cathedral-like chambers; the sides are solid salt, [348, image, 349] sparkling with crystals; the floor is solid salt; the roof is solid salt, left by the excavators, forty or perhaps sixty feet square. When the interior is lighted by dynamite the effect is superbly weird and grotesque. The salt is blasted by dynamite, loaded into cars which run on rails to the elevator, hoisted, and distributed into the crushers, and from the crushers directly into the bags for shipment. The crushers differ in crushing capacity, some producing fine and others coarse salt. No bleaching or cleansing process is needed; the salt is almost absolutely pure. Large blocks of it are sent to the Western plains for “cattle licks.” The mine is connected by rail with the main line at New Iberia.^[See also perrin1891, 106, which says that “a branch [of the Southern Pacific Railway extends from New Iberia to the salt mines.“]

Will Jones notes that there is a reference in Ann Patton Malone’s Sweet Chariot, p. 97:

After the war, a fraction of the former slaves wandered back to the only home many had ever known, and a freedman account book for 1866-67 documents the return of a dozen or more of the Petite Anse workers.

Her citation is: “Plantation Account Book 4, 1866-67, Avery Papers.” which are at the SHC.

Miscellaneous

- Post by Tabasco Company historian on earliest map of the island

- In the early twenty-first century, the mine had “ten levels—the lowest is about 1,500 feet under the surface—and more than 100 miles of roads and caverns.” But an engineer quoted in 2007 predicted that within the century, the mine would be closed. Operations are only possible up to a certain depth, below which temperatures become too hot.34

- Photograph of historical marker about salt mines in 1968

See also H. S. Kneedler, Through Storyland to Sunset Seas: What Four People Saw on a Journey through the Southwest to the Pacific Coast (Cincinnati: A. H. Pugh Printing Co., 1898), Chapter 3 available on Google books; Allen C. Redwood, “A Little World,” Scribner’s Monthly 22, no. 4 (August 1881), link. On Attakapas Indian artifacts on the island, see perrin1891, 96–99; Charles Dudley Warner, “The Acadian Land,” Harper’s New Monthly Magazine 74 (February 1887), 334–355, link.↩

H. S. Kneedler, Through Storyland to Sunset Seas: What Four People Saw on a Journey through the Southwest to the Pacific Coast (Cincinnati: A. H. Pugh Printing Co., 1898), 28–29, available on Google books.↩

On the Rock-Salt Deposit of Petit Anse: Louisiana Rock-Salt Company (New York: American Bureau of Mines, 1867), link, 18. This basic story was also told in “Avery’s Salt Island,” New Iberia Sugar Bowl, November 10, 1870.↩

Thomas O. Moore to Daniel D. Avery, August 12, 1862, Records of Ante-Bellum Southern Plantations, Series J, Part 5, Reel 11, Frames 571-572, link.↩

Moore apparently visited on July 31, 1862. See Register of Visitors at Petit Anse Island from 1859 to 1866, Avery Family Papers, Records of the Antebellum Southern Plantations, Series J, Part 5, Reel 11, Frame 874-885.↩

Thomas O. Moore to Daniel D. Avery, August 12, 1862, Records of Ante-Bellum Southern Plantations, Series J, Part 5, Reel 11, Frames 571-572, link.↩

Detail Exemption for John M Avery, Avery Family Papers, Records of the Antebellum Southern Plantations, Series J, Part 5, Reel 11, Frame 573, link.↩

Avery Family Papers, Records of the Antebellum Southern Plantations, Series J, Part 5, Reel 11, Frame 581.↩

See Register of Visitors at Petit Anse Island from 1859 to 1866, Avery Family Papers, Records of the Antebellum Southern Plantations, Series J, Part 5, Reel 11, Frame 874-885. A visit from a Mr. Carpenter, from Jefferson County, Mississippi, on September 5, and Col. Charles Baskerville, from Mississippi, in October, may also have been related to the salt. There was also a visitor from Tennessee at the end of September, and a G. Ralston of the CSA in early October.↩

Richard Taylor, Destruction and Reconstruction: Personal Experiences of the Late War (New York: D. Appleton & Co., 1879), 114. This must have been after August 1862, when kerby1972 says Taylor arrived in Opelousas (p. 21). Kerby also says “five hundred Negroes—guarded by two companies of infantry and a section of artillery—were producing over 1,300 bushels of crystal salt per day” (70).↩

A J. P. Broadwell is listed in the plantation register on September 8, 1862. Register of Visitors at Petit Anse Island from 1859 to 1866, Avery Family Papers, Records of the Antebellum Southern Plantations, Series J, Part 5, Reel 11, Frame 874-885. May also be W. A. Broadwell, who later became a cotton purchasing agent for Kirby Smith’s Cotton Bureau, according to this article.↩

H. S. Kneedler, Through Storyland to Sunset Seas: What Four People Saw on a Journey through the Southwest to the Pacific Coast (Cincinnati: A. H. Pugh Printing Co., 1898), 30, available on Google books.↩

On the Rock-Salt Deposit of Petit Anse: Louisiana Rock-Salt Company (New York: American Bureau of Mines, 1867), link; Ben Prescott to John Moore, January 28, 1863, Records of Ante-Bellum Southern Plantations, Series I, Part 6, Reel 17, Frame 820-821.↩

See Edward J. Day to D. D. Avery, October 8, 1862, Avery Family Papers, Records of the Antebellum Southern Plantations, Series J, Part 5, Reel 11, Frames 576-577.↩

Taylor to Gen. J. C. Pemberton, November 10, 1862, OR, XV, 860. See also Taylor to General Johnston, January 24, 1863, OR, XV, 958; S. Cooper to Taylor, November 12, 1862, OR, XV, 864.↩

On the Rock-Salt Deposit of Petit Anse: Louisiana Rock-Salt Company (New York: American Bureau of Mines, 1867), link, 13, 18. The same report advised against further use of powder to excavate: “It is certain that the mode of mining in pits, as hitherto carried on, would be wholly impracticable for any length of time; since to continue a large production in this manner would require a constant increase in the number and size of the excavations, and expose the salt to contamination from sand, and to the action of rains, which could not fail eventually to destroy the mines, and reduce operations to the old basis of boiling.”↩

Avery Family Papers, Records of the Antebellum Southern Plantations, Series J, Part 5, Reel 11, Frame 587.↩

On the Rock-Salt Deposit of Petit Anse: Louisiana Rock-Salt Company (New York: American Bureau of Mines, 1867), link, 18. Around ten pits were opened during the war, three devoted to Mississippi, Alabama, and Georgia; one worked by the Confederate Government; and four devoted to members of the Avery family, including John M. Avery, McIlhenny, and Daniel D. Avery. All of these pits struck salt at 12 to 17 feet below the surface and had found salt at depths ranging from 10 to 38 feet below first strike. See Appendix III.↩

Tri-Weekly Telegraph, December 1, 1862; and November 28, 1862.↩

“Items of Interest,” Houston Telegraph, supp., December 15, 1862, link.↩

“By the Orange Train,” Tri-Weekly Telegraph (Houston), November 24, 1862. For another report of the works being threatened, and a commentary about when the salt had been discovered there, see Tri-Weekly Telegraph, December 1, 1862.↩

On the Rock-Salt Deposit of Petit Anse: Louisiana Rock-Salt Company (New York: American Bureau of Mines, 1867), link, 18; OR XV, 296-7. For more on Union movements around the Island, and the eventual destruction of the works there in the spring of 1863, see kerby1972, pp. 98-107, and winters1963, p. 231–231, which cites the following sources in a footnote: “[Official Records, XV], 297, 324, 361, 373, which says that”Negro women were ravished in the presence of white women and children" during a march from Indian Village to New Iberia," 382, 399; Morris, The History of a Volunteer Regiment, 104; Ewer, The Third Massachusetts Cavalry, 76; Irwin, History of the Nineteenth Army Corps, 123-24; lonn1933, 32–33, 192–93, 208; perrin1891, 97–98.↩

Dudley Avery to General R. Taylor, June 2, 1864, Avery Family Papers, Records of the Antebellum Southern Plantations, Series J, Part 5, Reel 11, Frame 603.↩

Executive Office to Daniel D. Avery, September 16, 1864, Avery Family Papers, Records of the Antebellum Southern Plantations, Series J, Part 5, Reel 11, Frame 605.↩

On the Rock-Salt Deposit of Petit Anse: Louisiana Rock-Salt Company (New York: American Bureau of Mines, 1867), link, 19.↩

On the Rock-Salt Deposit of Petit Anse: Louisiana Rock-Salt Company (New York: American Bureau of Mines, 1867), link, 20–21.↩

On the Rock-Salt Deposit of Petit Anse: Louisiana Rock-Salt Company (New York: American Bureau of Mines, 1867), link, 23.↩

See also this history of the salt mines.↩

Louisiana Rock Salt Company, Chemical Analysis of Louisiana Rock Salt and Certificates of Packers (New Orleans: Picayune Office Print., 1869), available on Hathi Trust; H. S. Kneedler, Through Storyland to Sunset Seas: What Four People Saw on a Journey through the Southwest to the Pacific Coast (Cincinnati: A. H. Pugh Printing Co., 1898), 30, available on Google books.↩

“Avery’s Salt Island,” New Iberia Sugar Bowl, November 10, 1870.↩

See rothfeder2007, 73–74, quoted on 73.↩