Salt Works

A variety of salt works in northeast Texas and Louisiana helped to supply the Confederacy with the needed commodity. To produce the large quantities needed for regions that could not be reached by imports because of the blockade, slave labor was often used. For more on their role, see lonn1965. For evidence of the scarcity of salt in Texas, see the diary of Eliza McHatton.

As evidence of their significance, note that the Houston Telegraph pointed in 1862 to discoveries salt on Avery Island and elsewhere as a sign of God’s providence for the Confederate cause:

If anything were wanted to prove that Providence favors our cause, in addition to the multitudes of proofs we have already had, we might find it in the recent discoveries of salt in such abundance all through the country.1

General Information

Methods

My findings so far confirm generalizations drawn by gilbert1972, p. 9:

Throughout the South it was customary for the plantation owner to take his slaves to the salt works during the summer months to manufacture a sufficient amount of salt for the ensuing year. Usually two or three of the smaller families would combine their resources and manpower to manufacture their next year’s salt mines.

Commercial operations like the ones described below often rented furnaces to individual families as well. In either case, a significant labor force was required “to bring in the wood, pump the water, store the salt, dry it properly, etc.”2

Prices and Measures

According to gilbert1972, which discusses the Texas salt works and draws heavily on lonn1965:

| 300 gal. water | = | 1 bushel salt |

| 1 day of work | = | 100 bushels |

| 1 bushel salt | = | ~50 pounds |

| 1 sack salt | = | 200 pounds |

| Yrly salt intake | = | 50 lbs / person |

Prices varied widely throughout the war, but according to lonn1965, p. 44, “the tendency was upward.” Lonn and Gilbert both suggest that prices were kept lower in the Trans-Mississippi because of salt deposits in Texas and Louisiana, citing for example a schedule of prices paid by the army in Texas that cited salt at $2.50 per bushel. But testimony from A. H. Abney and John Williams (see below under Brooks Saline) suggest that prices climbed much higher per sack, reaching $50 or $100 at times.

Texas Salt Works

See also Salt industry in the Handbook of Texas; and discussions in the First Annual Report of the Geological and Agricultural Survey of Texas (1874), pp. 126–127.

A notice in the Houston Tri-Weekly Telegraph from November 24, 1862, may have been related to salt:

A sugar planter who can spare his kettles can learn at this office where he can sell them, at high rates, and hire out half a dozen negro men at $25 per month, and the money in advance. Or, if he will not sell his kettles, he can get new ones for them as soon as they can be cast, or he can get salt for them.

The legislature appropriated $50,000 to the Texas Military Board for the production of salt, and also passed a resolution requesting Gen. E. Kirby Smith to detail persons engaged now or hereafter in the manufacture of salt, to the extent of 20 bushels per day

Brooks Saline

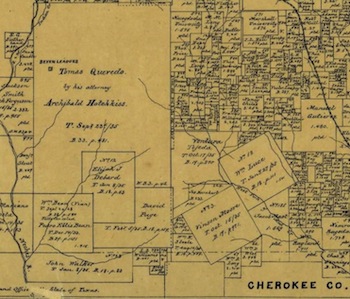

Clip from an 1880 cadastral map of southwestern Smith County, showing the Seven Leagues post office and the Bean grant where Brooks Saline was located.

Also known as Neches Saline or Gardiner Saline, this salt works was located in the southwestern corner of Smith County near the Cherokee County line, on land originally granted to Peter Ellis Bean.

At the time of the Civil War, the saline was operated by James Oden Brooks, often identified as J. S. O. Brooks, a salt maker from West Virginia who had relocated to Texas on the eve of the war. It is now covered by Palestine Lake, according to skinner1971. Excavation done before it was covered, however, revealed evidence of its existence. For much more information on Brooks’s operations, see gilbert1972.

Various sources report that over 200 or 300 slaves worked these deposits during the war, and in an advertisement appearing in the Marshall Texas Republican for December 2, 1864, Brooks solicited the hire of “100 Negroes” for the next year “or during the war.”

Refugeed slaves from Louisiana met some of this demand for labor. An article in the Tyler Reporter reports a runaway slave from the Saline owned by a Louisiana officer. Also, during the war John Williams, who had relocated to Larissa, TX in northeastern Cherokee County, hired out some of the nearly 100 slaves he brought from Louisiana to Brooks, as did Richard L. Pugh.3 Williams later reported a high demand for slaves for hire around the saline, where “a high price could be obtained payable in Confederate notes.” Apparently Robert Campbell Martin, Sr. wrote to Williams in early October 1864 to ask about the salt works and received this informative reply:

It was necessary for me to visit the Saline before I could answer your inquiries as to salt. You can purchase it at $50 a sack (possibly 40$) in new issue or interest bearing notes, or 100$ a sack for old issue. There is however a disposition to discard the old issue, and I think it would be safest to send the new or interest notes if you can get them, wheat can be readily exchanged for salt, say 5 bushels for a sack, meal is not wanting & they do not seem to care much about Louisiana State notes. There is a demand here for Negroes & a high price could be obtained payable in Confederate notes. The usual way of hiring here however is to fix the hire at old prices say from 10$ to 15$ for men & from 8 to 12$ for women, (without encumbrance) and take produce at old prices, say 75 cents for corn, 1$ for wheat etc etc. The party hiring them to cloth etc.—When you want salt send to me, & I will try to obtain it.4

A man from Louisiana named Grissamour or Grisamore is also mentioned by Robert Campbell Martin, Sr. as working salines in this area.

For a map of the deposits around Brooks, see this government report (PDF). For more information, see the TSHA article on Neches Saline

A petition from citizens of Anderson County also cited Thomas L. Garland as one of the people working salt around the Neches Saline, in a letter to the governor requesting his exemption from the draft as a “public necessity.”5

Steen Saline

Located in northern Smith County. Some sources indicate there was extensive work here during the Civil War.

E.g., William B. Phillips, The Mineral Resources of Texas, in Bulletin of the University of Texas, no. 365 (1914), p. 218:

The salines of Smith county were worked extensively many years ago, especially during the Civil War. At the Steen Saline, five miles east of Lindale, three thousand men were employed. The wells were shallow, and the salt was recovered by evaporation in pans, kettles, etc. Twenty furnaces were in operation, and output was 12,000 sacks a day. A bushel of salt was obtained from 190 gallons of the water.

About half a dozen men were also exempted from conscription and detailed as salt makers at this Saline, including W. S. Butts, Sam P. Lemay, J. J. Dudley, W. A. Ray, J. B. Morris, W. D. Walker, and Sam Prather.

Jordan’s Saline

Founded by landowner Samuel Q. Richardson, Jordan’s Saline, later known as Grand Saline, was located in Van Zandt County and had been worked for salt even before the Civil War.6

There is some evidence that refugeed slaves were hired out there during the war, judging by an 1863 runaway ad.7

A visitor to the area after the War reports significant wartime production: 1,000 sacks of salt at 200 pounds each every day. Likewise, Flake’s Bulletin reported in 1869 that “the Kaufman Star says the most extensive saline in the State is in Van Zandt county. From $75,000 to $80,000 worth of salt is annually manufactured at Jordan Saline, and its proprietor, Hon. S. Q. Richardson, will soon realize a princely fortune by his industry and energy.”8 The completion of the Texas and Pacific Railroad also apparently helped to expand Richardson’s operations, according to an 1874 article in the Dallas Weekly Herald.9 According to kerby1972, the Saline had a daily output of “3,000 bushels (ten times the yield of any other Texas mine)” (69). See also the Texas Almanac for 1868, which reported that “during the war, thousands of bushels were made here and wagoned hence hundreds of miles,” and referred to another similar saline in Smith County.

The records of the Texas Military Board also show that during the war the state was encouraging salt production around here under the auspices of its general agent, A. H. Abney. One letter from the Board to Abney in August 1864 laid out its reasons for wanting continuous salt production there, stressing that it would be a profitable business venture for the state while also benefiting citizens of the country. The Board also told Abney that state-contracted teams could be sent to transport salt to Austin.

An incident reported in howell2012, p. 14, also suggests Richardson hired freed people after the War who were terrorized and executed (with gunshots in the mouth) by white terrorist groups. See also Richardson’s letter to Governor Hamilton in September 1865.10

Miscellaneous

- William Littlejohn apparently planned initially to transport salt from somewhere in Texas to Shreveport.

- Thomas Pugh Martin went to work for a salt maker, perhaps near Tyler, towards the end of the war.

- In a letter to Governor Francis Lubbock, J. L. McMeans requested exemption from the draft because he was making 24-36 bushels of salt daily in Palestine, having recently hired, “at enormous prices, twenty odd negro fellows.” His letter also mentions J. S. O. Brooks and a J. B. Miller as exempted salt makers in Smith County. (Miller is the author of several salt orders sent to Richard Pugh in 1864, like this one.)

- William Hamilton of Corsicana, Texas, applied for exemption from military service on grounds of his being a “salt maker” in March 1864, perhaps around Jordan’s Saline.11

- Some “Salt Lakes” south of Corpus Christi were also being operated for salt during the war, apparently with oversight by a Confederate officer.12

- There was also a salt works in Jack County, according to a petition of citizens requesting the detail of some Reserve Corps soldiers to work there. The petition says that the works made an average of 40 to 50 bushels a day, but that recent frontier troubles had made it unsafe “to take negroes to said salt works,” making it impossible to hire labor.13

- A group signing themselves as “Thompson Reed & Co.” requested that Andrew Jackson Hamilton give them privileges to work a saline on Hubbards Creek some time immediately after the war.14

- The Ninth Legislature passed a resolution asking the Texas Military Board to look into working salines “near Double Mountain” and appropriating $5000 for this purpose.

Louisiana Salt Works

Avery Island

A Western Louisiana salt dome called the Island of Petite Anse (also known as Avery Island developed into a major site of salt production between the spring of 1862 and its capture by Union forces in 1863.

Lake Bistineau

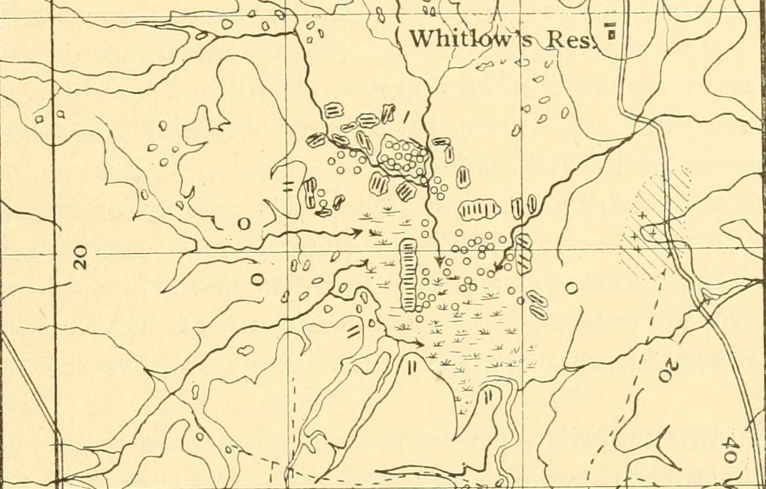

An 1899 sketch of Rayburn’s Salt Works, with circles showing locations of wells and hashmarks showing furnaces, from Harris and Veatch, Preliminary Report, p. 53.

Described by drake1966 as “the most important in Louisiana” after Avery Island. Near Lake Bistineau around Bienville was also the Rayburn’s salt works, which may have been the one that the Drakes referred to. An 1899 geology report claimed:

[Salt mining increased upon] the breaking out of the Civil war, when the restrictions imposed on the importation of salt by the federal blockage, caused it to have a very greatly enhanced value. The fame of Rayburn’s lick spread, and in 1862 men came from far and wide, bringing with them gangs of negroes. Hastily built shelters were put up, the valley was soon dotted with shallow wells from 15 to 20 feet deep …15

A travel guide written by a Federal WPA author in the twentieth century still found a local memory of Confederate women bringing “their slaves to assist them” in obtaining salt at the Rayburn dome, where as many as 100 wells were in operation.

Miscellaneous

- Kate Stone mentions many of their slaves being at salt works at Winnfield, Louisiana, during the war. See 1948 news report about salt in Winnfield.

- Ben Prescott discusses plans to transport salt from “the Island” up the Red River

- St. Mary Salt Works

- See report by Ian Brown on prehistoric Amerindian salt production in Louisiana.

“Items of Interest,” Houston Telegraph, supp., December 15, 1862, link.↩

gilbert1972, p. 9. See also lonn1965, 129–136.↩

Robert Campbell Martin, Sr. to W. W. Pugh, September 2, 1863, Transcription in Martin-Pugh Collection, NSU, Item 373. See also lathrop1945, p. 292n15.↩

John Williams to Robert Campbell Martin, Sr., October 16, 1864, Transcription in Martin-Pugh Collection, Nicholls State University, Item 612.↩

Petition of Citizens of Anderson County to Pendleton Murrah, [1863?], Records of the Governor Pendleton Murrah, Texas State Library and Archives Commission, Box 301-46, Folder 55.↩

See A. W. Moore’s impressions of the saline in 1846.↩

For more on Richardson and Jordan’s Saline, see Wentworth Manning, Some History of Van Zandt County (Des Moines, Iowa: Homestead, 1919), vol. 1, pp. 146ff.↩

“Texas Items,” Flake’s Bulletin, July 21, 1869, p. 8. Found in America’s Historical Newspapers (Readex) by searching for

"Q. Richardson" AND (salt OR saline).↩See also an 1873 article in the Houston Telegraph.↩

The original of this letter is in Records of Texas Governor Andrew Jackson Hamilton, Texas State Library and Archives Commission, Box 301-50, Folder 24.↩

Letter of introduction from William L. Langdon to Pendleton Murrah, March 30, 1864, Records of the Governor Pendleton Murrah, Texas State Library and Archives Commission, Box 301-45, Folder 25. See also a petition of citizens on his behalf, in Petition of Subscribers from Navarro County to Pendleton Murrah, [1864?], Records of the Governor Pendleton Murrah, Texas State Library and Archives Commission, Box 301-46, Folder 54. The petition notes that “the demand for salt is great, and that at the present time not more than one eighth of the quantity of salt is made which was made at this time last year at Jordan Saline. (On 1st April 1863 there were 100 to 125 furnaces in operation, now not more than 10 to 15.)”↩

Stephen H. Darden to Pendleton Murrah, September 7, 1864, Records of the Governor Pendleton Murrah, Texas State Library and Archives Commission, Box 301-46, Folder 41. See also Murrah’s letters on the subject dated October 1, 1864, Records of the Governor Pendleton Murrah, Texas State Library and Archives Commission, Box 301-47, Vol. 2. But see also note after the war about the absence of supervision at the “Sal del Rey” lake in Hidalgo County. Robert B. Kingsbury to Alexander J. Hamilton, November 29, 1865, Records of the Governor Andrew Jackson Hamilton, Texas State Library and Archives Commission, Box 301-51, Folder 37. Kinsburgy was a tax collector and believed that salt was being illegally extracted in order to avoid an excise tax on salt.↩

Petition of Citizens of Jack County to Pendleton Murrah, n.d., Records of the Governor Pendleton Murrah, Texas State Library and Archives Commission, Box 301-46, Folder 55.↩

See Thompson Reed & Co. to Andrew Jackson Hamilton, n.d., Records of the Governor Andrew Jackson Hamilton, Texas State Library and Archives Commission, Box 301-52, Folder 58.↩

See Gilbert Harris and A. C. Veatch, A Preliminary Report on the Geology of Louisiana (Baton Rouge, 1899), link, for more on these works and Drake’s. Quoted on p. 122.↩