William French

The steamboat William French was named after a “master ship carpenter and engine builder” credited with “placing the first high pressure engine upon a Western steamboat.”1 It is the ship by which the Cirode Family took Henrietta Wood from Louisville to New Orleans sometime in 1837 or 1838.

Evidence about the origins of the boat suggests that Wood’s trip may have been in 1838. The Times-Picayune noted the arrival of the “new steamer” in New Orleans on May 13, 1838:

A NEW STEAMER.—A new and splendid steamboat, a perfect gem in her way, called the Wm. French, made her appearance at our levee yesterday. The passengers, one and all, speak in the warmest terms, not only of the speed and accommodations of the beautiful boat, but of the attentions paid them by her gentlemanly and experienced commander, Capt. Reid. Success and long life to both say we.2

A later ad in the Times-Picayune on July 8, 1838, described the William French as a “splendid passenger boat” and mail carrier that would be leaving soon for Louisville from Poydras Street.3 And the next year, it implied that the boat was able to make the trip from New Orleans to Louisville and back in “eleven days and twenty hours.”4

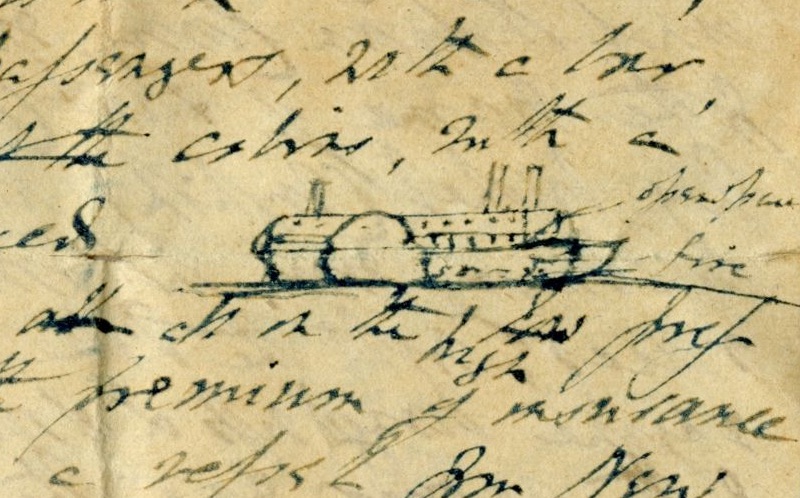

Sketch of the William French by an 1840 passenger, from Portal to Texas History.

The famous “Lytle List” of steamboats lists the vessel as a sidewheel, 265-ton vessel that was built and operated out Pittsburgh, and also dates it origins to 1838, noting that it was either abandoned or disappeared from the records in 1845.5 An 1838 report to the Secretary of the Treasury about steamboats in Louisville also describes it as a “new boat” built in 1838, though it names Louisville as the city of origin and credits French himself as the builder. This report lists the tonnage as 265 and gives the length of the boat (163 feet from stern to stern), breadth (25 feet at broadest point), and depth (7 feet from spar-deck to keel). Its engine is “high” pressure and the captain is listed as Reid. It is the newest boat in use in the district of Louisville.6

The boat seemed to be used for mixed purposes, but an 1840 article reporting on a poll of the vessel’s passengers to gauge their preferences in the presidential campaign stated that there were “163 deck, and 67 cabin passengers, most of whom were from Illinois, Indiana, and Missouri.”7

Ads for the boat appeared in the Louisville Courier-Journal.8 And they also indicate that the boat was bringing commodities back from New Orleans (Havana sugar and coffee, Malaga wine, etc.) for sale by Louisville merchants just like Henry Forsyth, though it seemed particularly important to the business of a firm named Buchanan and Gray. It also is frequently thanked in both Louisville and New Orleans papers for bringing news from the other city, as well as from intermediate points like Vicksburg. One example: “We are indebted to the Wm. French (God bless that winged steamer!) for New Orleans papers of the 30th ult.”9 It was prized especially for its light draft, which meant that it took mostly passengers instead of cargo and could be depended on to get between Cincinnati and New Orleans regardless of the season.10

The boat was mentioned in a brief New York Times article about Mississippi River steamboats, published in 1864.11

An 1841 letter from Thomas Falconer, an Englishman who was a passenger on the boat, gives a small sketch of it and also provides more details of what a trip aboard the boat was like:

My dear John, in my last letter I gave to you an abstract of my journal to Louisville. At this city I took my place in a steamboat the William French, paying 25 dollars to go to New Orleans, the distance being 1426 miles. Five pounds for 4 hundred miles was not dear. You must know that in all the [Canal?] & Steam boats the fare includes the having of a berth & breakfast, dinner & supper. You are lodged and boarded the whole time you remain on board. The steamers differ from ours in many respects. The part of the boat flush with the water is entirely used as a hold for luggage. On the deck over the hold is the engine, the boilers, fire places, depot for wood & kitchen. The engines & boilers occupy the greater part of this space & at the two ends, the wood for the fires is placed, for wood & not coal is used for the fires of the boilers. Above the engine house is a long saloon or cabin, divided about one third down [by] two folding doors. The smaller part, is the Ladies Cabin, the larger, that of the men. There is a sort of ante-room for her [or day?] passengers, with a bar, at which spirits & wines are sold. A gallery runs round the outside of the cabin, with a considerable open space in front, in which, freight is generally placed. When the engines [lept?] to work, they jar & shake the whole boat. They are all on the high pressure principle, & very frequently explode. The insecurity is such, that the premium of insurance on a steam boat from New Orleans to Louisville, is as high as on a vessel from New Orleans to England. The stokers who manage the fires are slaves & make a most infernal singing & I have no doubt are a vicious & cruel set. When we got to [Smithland?] on the night of the 24th (at the head of the Cumberland River) there was a fight among the boatmen there. They had their knives out, some persons were wounded but they said that no [pass?] had been killed for [three months?]! Twice a day the boat stops to take in wood, which is sold upon the banks of the River. On these occasions I generally went on shore.—[I saw?] the blacks [?], to ‘Tam’ & ‘Got Tam’ one another & to laugh. In these steamers, a bell is rung just as it gets light in the morning as a signal to get up. In the state rooms, there are no wash hand basins, nor any place for one. You half dress, & then walk out up the gallery of the boat. There you find a [soiled?] towel, two or three [?] basons, a bit of soap, & a large bowl of water out of the barrel you dip what water you want & wash yourself. If you like to be shaved by another, a black barber on board will lather you, & charge ‘a bit’ or 12 1/2 cents equal to 6 pence for his trouble. If you please, you may shave yourself. This I of course always did, having towels, razor, comb & soap of my own. In the anteroom, a brush & a comb hang suspended by a small chair & they are generally used by all the passengers! Another bell then rings as a signal that the women have come into the Gentlemens Cabin & that breakfast may be consumed, for no person sits down until after the women. The breakfast table is well supplied. Immense beef steaks are also at the top & bottom, cakes like oatmeal cakes, hot rolls, steaks, fish, potatoes, coffee & tea, are always served. I am moderate in my eat, & dry household bread & tea contents me. Though you wait for the women to begin breakfast, you do not wait until they finish. Each man gulps down his breakfast & walks away. One by one they fall off. A second breakfast is then laid out for the 2nd class passengers & the white servants, or whites, employed in the management of the boat. When they have finished, a third breakfast is laid out, for the black servants. Between breakfast & dinner, you read or converse. The majority, on the [illegible …] playing cards & gambling all day. Dinner is served at one o’clock. It consists of turkey [parts?], venison, pork, mutton, fish, hominy, beef, vegetables, &c. Always an abundance, with puddings & pies. Fowl & potatoes, or Turkey, always contented me. There are three dinners arranged in the same way as the three breakfasts. The supper is the same as the breakfast. … You rarely see an American with a book in his hand. The first three days that an American comes on board he occupies himself in reading & re-reading some half dozen newspapers that he has brought with him. Their conversation, if kept to themselves, relates to dollars, to prices current, the value of cotton, & the course of exchange. The making of money appears to be their chief pursuit, from childhood to old age–from the time they can talk to the time they die. At Louisville a very find Court House is just completed. … On the wharf I saw a large quantity of the produce of the county, brought down in flat boats … On the night of the 22nd of Decr. (1840) we left Louisville to go down the Canal, made in consequence of the Falls of the Ohio & we stayed that night & the greater part of the next day, at a place called Portland. There we took in about 30 horses to be landed at Natchez & New Orleans. On the 24th we were at evansville * Henderson & then Smithland. On the 25th at mid-day we were at Grand Cairo, a new town at the junction of the Ohio and the Mississippi. … We now got upon the great river Mississippi, with its [snaggs?] & sawyers, or large trees, the roots of which are buried in the sand & the trunks of which reach the bottoms of boats & frequently wreck them. At our very entrance of the Mississippi was one of these large snags. The water was low & we could see an infinite number of them in our course. From the junction of these two rivers until the borders of Louisiana are reached, the river & its banks nearly a uniform appearance. The forest of cotton trees (not the cotton plant), of ash & oak, intermingled, with cane brake, reaching to very margin of the river. No hills or mountains to disturb the [perch?] of the scene, except on two or three points where there are hills of no great height. In or course the breadth of the Mississippi greatly varies. In some places it is three miles wide & here at New Orleans its breadth is not a mile. Cattle graze on the canebrake and are said to be very fond of it. Farmers leave them to browse on it, without any other food during the whole winter. Decr. the 26th we reached Memphis & I was glad to see a most dangerous part of our cargoe landed. After I came on board the French & had started, a fellow passenger with me in the Tioga, told me, that he saw removed from the Tioga to the French, 16 barrels of gunpowder. It was placed on the point of the [relief?], in the open space at the end of the gallery. At first I was rather uneasy at the information & the first night after the information, I was not surprised to see my cabin almost lighted with the train of sparks which constantly [arise?] from the chimney of a steamer’s wood fire. Nor at the recollection that the gunpowder was placed not 8 feet from the doors of the fires. [I know?] I went to sleep and from the 22nd to the 26th I used to look at this dangerous load, calculating the consequences of its explosion, & could hardly smile, as seeing men smoke their cigars close to the canvas laid upon the top of it. When we arrived at Memphis, one by one, the whole sixteen barrels were removed on shore, marked H. F. F. When I said to the man [heaving?] it, ‘a good large quantity of gunpowder this,’ he said, yes, the captain ought not to have brough such cargo. The carelessness respecting human life in this country is surprising. I ought to have left the vessel when I knew the cargo we had—but I suppose that companionship makes men fearless. On the night of Decr. 27, I was awakened by the man in the berth above me, jumping out of bed & rushing into the cabin, where I saw the other passengers, running out, some with life-preservers in their hands. … It had struck a snag and there was an alarm that it was sinking. The damage was over-rated, but we remained all night tied to the shore & the steam was let off. I was not aware until this night, that the fear of drowning was so general on board these boats. … The next day an Arkansas man came on board, who complained ‘that the country was so cramped up, it had taken him six hours to find a bear!’ In his conversation with another man he said he did not know where his family lived. “He believed they were all squandered but that they were respectable.” The truth is, there is no family affection in this country. Every mother complains that she is disregarded by her children. Few brothers keep up even an acquaintance. They boast of a disregard of their feelings. … On the 29th we came to Natchez. The lower part of this town, under the hill, was utterly destroyed by a tornado in May last, yet it is now covered with houses. … The stories of murder &c. in this place, exceed belief. On the 30th we arrived at New Orleans, but I did not land until the next morning. … With this city I have been greatly pleased. Its Spanish & French houses remind me of European towns & it is very grateful [sic] to see a town that is not American. The increase of this place within the last two years has been wonderful. … New Orleans is a safe place for health at this time, but at other seasons, it seems to be the very House of Death.12

Quotes about French the man from Emerson W. Gould, Fifty Years on the Mississippi; or, Gould’s History of River Navigation (Saint Louis: Nixon-Jones Printing Co., 1889), p. 243 available on Google Books.↩

“A New Steamer,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, May 13, 1838, p. 2, found on Newspapers.com.↩

“Splendid Passenger Boat; U.S. Mail for Louisville,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, July 8, 1838, p. 3, found on Newspapers.com.↩

New Orleans Times-Picayune, May 12, 1839, p. 2.↩

William M. Lytle, comp., Merchant Steam Vessels of the United States, 1807-1868 (Mystic, Conn.: The Steamship Historical Society of America, 1952), p. 203.↩

Steam Engines: Letter from the Secretary of the Treasury, Transmitting, in Obedience to a Resolution of the House … information in Relation to Steam Engines (1838), 25th Congress, 3d. Session, House of Representativies Doc. No. 21, p. 318-319, available on Internet Archive.↩

Pittsburgh Gazette, April 30, 1840, p. 2, found on Newspapers.com.↩

See, for example, February 14, 1839, p. 3; February 1, 1839, p. 2.↩

Louisville Courier-Journal, June 8, 1839, p. 2, found on Newspapers.com. See also, for Vicksburg, New Orleans Times-Picayune, May 6, 1841, p. 2.↩

See “United States Mail Packet Steamer,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, January 1, 1841, p. 3.↩

“Steamboat Travel on the Mississippi,” New York Times, September 18, 1864.↩

Letter from Thomas Falconer to John David Falconer, December [January] 5, 1841, Southwestern University Special Collections, available on Portal to Texas History, accessed April 27, 2016.↩