Zebulon Ward

The man whom Henrietta Wood sued for her kidnapping in Wood v. Ward.

Vital Stats

Ward was born in Cynthiana, Harrison County, on January 14, 1822, one of ten children born to Andrew Ward and Elizabeth Headington Ward.1 See his parents’ marriage certificate.

Ward married Mary E. Worthen of Harrison County on January 9, 1851, as shown by a marriage certificate.2

He died on December 28, 1894, “at the family home, Fifth and Ringo streets,” in Little Rock, Arkansas.3

His tombstone confirms the birth and death dates given above.

Genealogy

Ward and Mary Worthen had ten children: five boys and five girls. In 1940, Arkansas Gazette reported Nettie Fenno of Boston, Mass., as only surviving child. Three grandchildren, Louise Ward, Sibley Ward, and Mrs. William H. Garnett (nee Worthen Fatherly), live in Little Rock at the time.4

His children included, according to 1894 obituary:

- William H. Ward (b. 1852)

- Zeb Ward, Jr.5 (b. 1859?)

- Mrs. Dr. W. E. Green (Addie)

- Mrs. Oscar Davis

- Mrs. Nettie Fenno

The older daughters, according to the 1860 census record, were Adelaide (Adda or Addie) Ward (b. 1854?) and Minnie Ward (b. 1857?). According to the 1870 census record, another daughter Nellie was born in 1860.

Ward also had a son named Thomas born in July 1855, according to Kentucky Birth Records.6

Ward’s brother, Andrew Harrison Ward, was a lawyer in Harrison County who went to Transylvania College sometime in the 1830s, eventually passing the Kentucky bar in 1844 and going on to a long legal and political career.7

Early Life

Sketch of Zebulon Ward from Louisville Courier-Journal, January 2, 1895, p. 7, available on Newspapers.com.

The 1820 census for his parents shows them living in Harrison County. The 1830 census entry shows them in “Eastern District” of Harrison County, and has a male between the ages of 5 and 10 in the household.8

On his mother’s side, Ward’s grandfather was Zebulon Headington, who arrived in Kentucky as early as 1785 and died in 1841. According to family history, he had served as a quartermaster in the Revolutionary War in Virginia.9

On his father’s side, Ward was descended from an Irish family that had settled in Virginia in the 1720s and then came to “Maysville by flatboat” (according to Ward’s brother) after the Revolutionary War. His father Andrew Ward settled in Harrison County in 1800 and knew the tanning trade; he and his young wife moved to Urbana, Ohio, at the invitation of his father’s cousin, Colonel William Ward, but returned to Harrison County prior to the War of 1812, in which Andrew Ward served.10

Steamboat Clerk

Family histories suggest Ward worked in the steamboat business as early as the late 1830s, when his brother Andrew Harrison Ward took a job as a purser on a Mississippi steamboat. A sister’s letter at the time said that “Brother Harry and Brother Zeb are both on The River now, and happy, of course.” His niece later reported that “Uncle Zeb remained ‘on the River’ much longer than Father did.”11

A brief notice in the New Orleans Times from 1874 states that “Zeb. Ward was a freight clerk on our Cincinnati and New Orleans steamers, with General Markland, twenty-five years ago.”12

An obituary for Ward likewise reports that:

Upon attaining manhood young Ward became a clerk on a Mississippi River steamboat, engaging in that occupation several years. Subsequently he went to Nashville, Tenn., but his health declined there, and he journeyed to Cuba, where a sojourn of some time restored his wonted good health. Returning home about the time the Mexican War broke out, he became imbued with the war spirit and left for Mexico and joined the American army, serving in the field with distinguished credit to himself. After the war, he contracted the California gold fever and resolved to join the exodus to the Pacific slope in the palmy days of 1849. He went thither by way of Panama and reached California after an eventful journey.13

According to a family genealogist, “at 21 years of age he embarked in the steamboat business in Nashville, Tennessee, followed by some time spent in business in Cuba”; the same source claims, like the obituary, that he fought in Mexican War and then joined Gold Rushers to California.14 ] He then returned to Kentucky and got into the steamboat business again in Covington, Kentucky.15

I haven’t been able to confirm all those details, though Ward’s rambling fits with this evidence:

- Haven’t found a record for him in the 1850 census.

- He doesn’t appear in the Harrison County Tax Assessment Rolls in any year between 1841 and 1852, even though many of his brothers and mother remain there.16

- A “Zebulon Ward” does appear in a list of recipients of letters published in the Sacramento Transcript throughout February and March 1851; see, for example, issue of March 4, 1851, found on GenealogyBank.com.

- A “Zebulon Ward” appears in a list of unclaimed letters in the New Orleans Daily Picayune, April 19, 1850, available on America’s Historical Newspapers.

- A “Z. Ward” appears on a passenger list for the steamship “Alabama” for “Chagres” (Panama?), published in New Orleans Daily Picayune, May 11, 1850, p. 1, available on Newspapers.com, and the Alabama did take forty-niners to California via Panama around this time; a “Z. Ward” then appears on a passenger list for the “steamer Northerner, for Panama” published in the San Francisco Alta California, October 31, 1850, p. 5, available on America’s Historical Newspapers.

- A “Z. Ward” checks into the Galt House in Louisville in December 1846, though he is listed as from “Jeffersonville,” and “Z. Ward” also has letters waiting for him in Louisville on July 1, 184817

The harder thing to confirm is his Mexican War service during this period. Zebulon Ward does appear at some gatherings for Mexican War veterans in Arkansas late in his life, but some of these “informal” gatherings seem to have included Civil War veterans too.18 I have been unable to find any official record of his Mexican War service, other than in family genealogies and his obituary, which may at least indicate that Ward himself claimed to have served.19

Sheriff in Covington

A birth record for one of his children from Kenton County, Kentucky, suggests he may have been in Covington by February 13, 1852.

The Kenton County Court Order books prove that Ward was a sheriff in Covington at the time of Wood’s kidnapping. At the start of the January term, 1853, Phil F. Brown, the sheriff of the county, appeared before the court to move that Zeb Ward, R. B. Broaddus, R. R. Sumerwell, William J. McDonnold, and C. W. McDonnold be admitted his deputies. He swears the oath as a deputy sheriff again at the March Term. By January 1855, a new sheriff, William H. Wood, has been elected, and Ward no longer appears as a deputy.20

A notice in the Covington Journal in April 1853 noted: “Mr. Ward has declined being candidate for Congress in the Second District, for fear of producing confusion among the Whigs of the district.” It is possible this is the same Ward.21

Ward appears on the tax assessment rolls for Kenton County in (May) 1853 with one slave (valued at $400), one horse, no land, and gold (and other valuables) valued at $75. The timing of the tax survey makes it unlikely, but possible, that this slave was Henrietta Wood. The next year’s assessment, in 1854, shows Ward as owner of 6 acres in Kenton County, valued at $1,000, along with 1 slave valued at $500, one horse, and gold (and other valuables) assessed at $50. In 1855, he is assessed for three slaves (one over 16 years of age), valued at $1,000, but now with no land. By 1856, Ward is no longer listed in Kenton County tax rolls.22

The Covington Journal reported an arrest of burglars at the Madison House by Sheriff Ward.23 A year later, Ward was involved in the capture of eight or nine slaves who had made it to Cincinnati; the arrest was made by U.S. marshals with the assistance of Ward.24

George Blackburn Kinkead (1849-1940) wrote a brief memoir of his childhood that refers to Ward at this time, referring to his love, as a boy, of riding on the stagecoach line from Covington to Lexington:

On one occasion Zeb Ward, a powerful man, then Sheriff of Kenton county, and his batch of criminals destined for the penitentiary at Frankfort, riding on top excited my curiosity to such a degree, that I made it unbearable for the other passengers by my cries to be taken up with them. Being so often with my father, Mr. Ward knew me well, and to stop my cries as much as to gratify me, at the next stage caught me by the arm, and to the consternation of my mother drew me through the opening, and seated me by his side, and in the midst of this much desired society. How I bragged of this adventure to the negroes on the farm.25

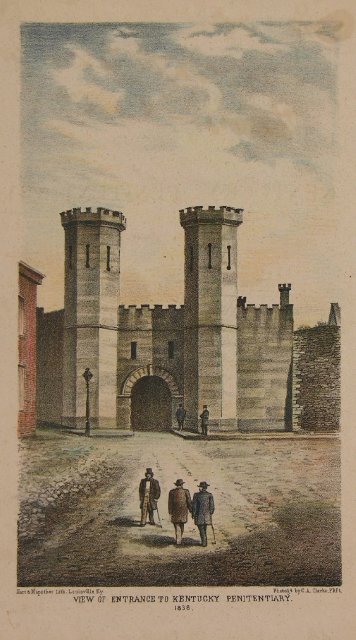

Lessee of Kentucky Penitentiary

He also was a lessee of the Kentucky penitentiary beginning in 1855. He does not show up in the Franklin County Tax Assessment rolls until July 1856, when he is shown living in the town of Frankfort, owning four slaves (two over the age of 16), valued at $2000. In 1857, he is shown with seven slaves (three over the age of 16), valued at $3800. And in 1858, he owns eight slaves (five over the age of 16), valued at $4400. He does not appear in 1859 or later in Franklin County tax rolls, and does not appear to have ever owned land or town lots while keeping the penitentiary.26

He is mentioned in the famous Wines and Dwight report on prisons, which mentioned Ward’s arrangement while critiquing the general principle of the Auburn contractual labor system.27 Their account, drawing on a “history of the Kentucky Penitentiary, by William C. Sneed, M. D.,” explained:

The history of the Kentucky penitentiary affords additional proof of the same thing. In 1825, the principle was adopted of allowing the keeper, in lieu of all other compensation, one half of the profits, after defraying the current expenses. Joel Scott was the first keeper under this system, and he served for nine years. The clear profits from convict labor during his administration were $81,136. Mr. Scott was succeeded by Thomas S. Theobald, who took the prison on the same terms. The aggregate profits of his administration of ten years, the average number of prisoners being less than one hundred and fifty, were $200,000; and one year they reached the extraordinary sum of $30,000. Every dollar of the state’s share—$100,000—was paid into the public treasury. In 1855, Zebulon Ward leased the prison for four years, at an annual rent of $6,000; and at the end of his term, he retired with a fortune variously estimated at $50,000 to $75,000. Mr. Ward was succeeded by J. W. South, who leased the prison for a like period, though at the advanced rent of $12,000 a year. He also, at the end of his four years’ service, is reported to have retired with an ample fortune, as the product of convict earnings.28

Sneed’s history goes into much greater detail about Ward’s administration, reporting that he was nominated for keeper of the penitentiary by a Mr. Cunningham, and elected by a vote of the legislature on February 20, 1854.29

The Covington Journal described the position as “the most lucrative one in the State of Kentucky” and said it was “glad that our fellow-townsman Mr. ZEB WARD has been elected Keeper. He is every way qualified, indeed admirably fitted, for the discharge of the duties, and will give general satisfaction.”30

Ward began his term as keeper on March 1, 1855, prompting Sneed to resign his position as attending physician.31

Sneed says archly that “Mr. Ward, though a thorough business man, had no previous experience in the management of such an institution.” But he kept some of the former guards and assistants. Ward was, in Sneed’s telling, a political appointee who received support from friends in high places, even though rumors of “his ill treatment of the convicts, and of the wretched condition of the sleeping apartments in the cell buildings” began to circulate almost immediately and sparked a grand jury investigation ordered by the circuit judge, W. C. Goodloe, in May. The grand jury gave a good report, dated May 23, as to the sleeping arrangements and cleanliness of the penitentiary grounds, but expressed “disapprobation of the severity of punishment inflicted on the convicts, in more instances than one, amounting, if not to a violation of law, is at least violating to the feelings of humanity.”32

View of Entrance to the Kentucky Penitentiary, 1838, Lithograph by C. A. Clarke, 1860

In his first annual report, Ward complained that many improvements were needed to make the prison “comfortable to the prisoners, and profitable to the State and keeper. The entire prison is behind the age. There are not workshops enough to give employment to the number of convicts now in confinement,” he complained.33

As of January 1856, there were 10 convicts in the penitentiary there for “assisting slaves to run away,” three for “stealing slaves,” and one for “emigrating to Kentucky, (free negro).”34 A complete Register of Prisoners as of 1848 and 1855 can be found at the Kentucky Department of Library and Archives, Reel 7009891, and it includes Calvin Fairbank, Thomas Brown, and a mulatto man named James Blackburn who was sentenced for enticing slaves to run away, and was identified by lash marks on his back.35

The physicians working for Ward praised his “kindness and attentive generosity and humanity.”36

On March 1, 1856, Ward began a new three-year lease of the penitentiary (of a projected six years); he paid a rent of $6,000 per year, plus all expenses. “By the provisions of this act the institution went into the absolute control and management of the keeper,” Sneed wrote. “The checks and restraints usually thrown around that officer were all now removed, and he had liberty to do as he absolutely pleased. No monarch ever had more unlimited control of his subjects, and no one ever exercised his own will more completely than the keeper of the penitentiary did, from the time the institution passed into his hands under this law, until the end of his term.” Sneed charged that Ward, the Governer, and the inspectors were all partisans together, making the whole arrangement a case of corrupt political patronage.37

In his second report, Ward complained again about the lack of machinery in the institution, focusing little on the condition of the convicts.38

Ward continued to manage the penitentiary until his term expired on March 1, 1859, when a new penitentiary elected by Democrats who had taken the legislature took over. Sneed’s summative judgment is that Ward completely “lost sight” of any “moral influence exerted over the inmates,” seldom allowing a sermon to be heard except in obedience to the law. “The law requiring the convicts who were unlearned to be taught so many hours on the Sabbath was a dead letter; and, in fact, all the laws in relation to their moral condition were neglected, and only one great idea made prominent, and that was—work.”39

Ward’s administration began at the same time Calvin Fairbank was imprisoned for helping fugitive slaves, though Fairbank apparently misdates his taking over of the penitentiary to 1854. Thomas Brown was another abolitionist imprisoned there who criticized Ward’s management in a memoir.

In 1858, Ward accompanied a shipment of “1,000 pieces of penitentiary bagging” to New Orleans aboard the H. D. Newcomb.40

Woodford County Farmer

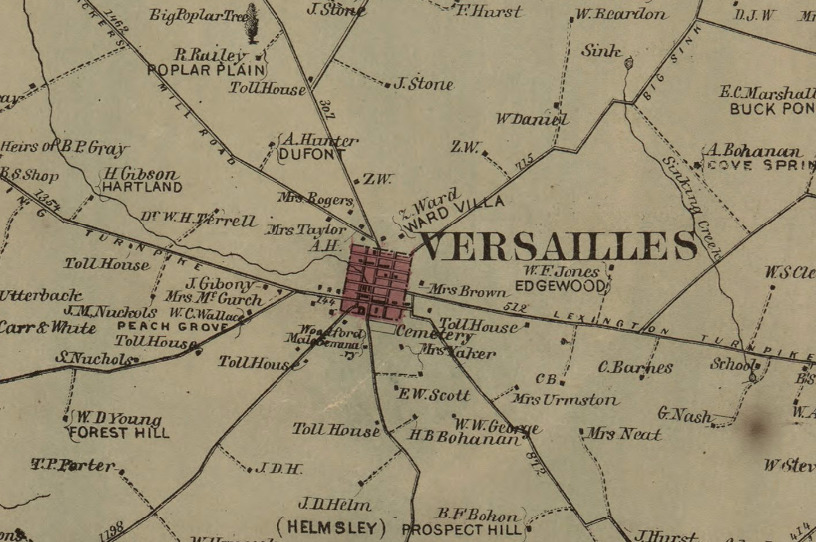

After his penitentiary lease, Ward purchased a large farm in Woodford County and relocated there.

Ward doesn’t appear to show up in Woodford County until 1859, after purchasing some land there in December 1858.41 He made an especially big purchase of 144 acres of land from H. B. Bohannon in May 1860 for $12,269, paid in increments (and partly in mules).42 Various other entries in county deed books show him purchasing property in the county or in Versailles between 1861 and 1866.43

His first appearances in the Woodford County Circuit Court Order Book are in Book AA, which begins in 1860.44

In the Woodford County Court Order Books, he first appears in September 1859, where the tax assessor reports an assessment on his property taken prior to May 1 but just now being recorded. He is listed as the owner of 443 acres of land valued at $33,250 and 15 slaves valued at $13,000, as well as cattle, horses, and value, for a total value of $71,450.45 He does not appear in the indices for Books M and N of the county court order books, which cover the years 1860-1867.

Some of Ward’s goods, specifically chairs and hemp bagging, are listed in a report of the Kentucky State Agricultural Society in 1858 and 1859, at which time he is listed alternately as a resident of Franklin County and Woodford County. He also purchased a harness horse for $700.

He appears to have been a founding member of the Agricultural Society, along with John Cunningham, of Paris, the state Senator who nominated him for keeper of the penitentiary.

In the 1860 census, a 38-year-old Zeb Ward is listed as a farmer in Versailles, Kentucky. Ward is listed as having been born in Kentucky. The value of his real estate was $60,000 and the value of his personal estate was $30,000. Along with Ward’s family, one laborer named John Cole (38, born in Kentucky) is listed as part of the Ward household.

Civil War Years

Tim Talbott found a letter from Zeb Ward to Henry Wise, showing that Ward sent a special hemp rope for John Brown’s hanging. Jack Shuler’s history, The Noose, appears to suggest that the rope Ward sent was actually used to hang Brown.

At the beginning of the war, according to the 1860 Slave Schedule of the Census, Ward owned 27 people.

He apparently sold some oats to the 36th Georgia Infantry of the Confederate Army in October 1862.

In 1888, Ward retold the story of guerilla raids on horse farms in Woodford County at a gathering with fellow “sportsmen” at the St. James Hotel in New York.46

Morgan’s Confederate raiders reportedly stole a mare worth $4,000 from Ward in 1862; also referenced here; for a similar raid narrative, see Extact of a letter from R. A. Alexander.47

Letter from Zebulon Ward to Kentucky Governor Thomas Bramlett, March 10, 1865, dated Lexington.

After the war, several residents of Woodford County filed suit against Ward for “false imprisonment, &c.,” during the war. Ward responded with a petition citing the March 3, 1863, act of Congress about habeas corpus, “setting forth the fact that the acts were done in obedience to the military authority of the United States, &c., and praying for a transfer of the case to a Circuit Court of the United States.” Judge Goodloe ruled in his favor, and the State Court of Appeals affirmed the decision.48

State Legislator in Kentucky

Ward was in the legislature from 1861 to 1862 or 1863, as a state representative from Woodford County.49 He was described in a Cincinnati paper in 1861 as “the Union candidate for the Legislature” from “Crittenden’s native county, Woodford.”50 He took his seat on September 2, 1861.

A search for “Zeb. Ward” reveals many of his votes in the Kentucky House Journal for 1861 and 1862, available on HathiTrust. (See also the governor’s message urging Kentucky to maintain its neutrality, and many joint resolutions proposed by representatives opposing slave emancipation.)

- Ward votes to support adoption of a report affirming Kentucky’s loyalty to the federal government

- Voted to instruct John C. Breckinridge and L. W. Powell to resign their seats in the Senate

- On some resolutions in December 1861 stating that Kentucky would not agree with the federal government emancipating or arming slaves, Ward votes affirmative

- Also part of a unanimous vote disavowing any intention by Kentucky to abolish slavery

- Vote for a concurrent resolution praising Lincoln’s reversal of Fremont’s order and calling for Simon Cameron’s dismissal

- Vote to raise an additional military force

- Chairman of a committee to investigate the INstitution for the Education and Training of Feeble-Minded Children

He is described by whartonwilliams1986, p. 122, as a “Unionist and a member of the state legislature,” whose farm joined Edgewood, the farm of W. J. Jones and his wife Martha. The Joneses (who were Confederate sympathizers) rented their farm to Ward in September 1863, and Martha Jones later registered a complaint, in an April 5, 1864, entry, that Ward had not paid the rent he owed (p. 155). During the war, both Ward and Jones appear to have hired enslaved men to each other to break hemp, a major agricultural product of the area. On January 25, 1862, for example, Martha Jones noted that “Men broke hemp today, 4 of Zeb Ward’s negroes here [hired]” and on August 10, 1860, “Willis hired men to Mr. Ward [a neighbor] today to cut hemp.”51

Ward vehemently opposed the Emancipation Proclamation and “the unconstitutional and iniquitous course of the Radicals” according to several reports.52 He tried to add an amendment to a Kentucky bill funding soldiers that would have required the soldiers not to fight to enforce the Proclamation.53

His obituary claimed that he served as an aide-de-camp on General Nelson’s staff and supplied horses to a cavalry raised by Gen. J. S. Jackson, later enlisting on Jackson’s staff before becoming a Government Purchasing Agent.54 He is shown on a list of Woodford County residents eligible for the draft, made in July 1863.55

In 1864 he was an alternate delegate from Kentucky’s “Union Democratic Delegation” to the National Democratic convention in Chicago, identifying him as a War Democrat.

Slaves who Joined USCT

Tim Talbott has a post about enslaved men owned by Zeb Ward who joined the USCT. Their names were:

- Clay Ballard (see postwar Freedmen’s Bureau claims in 1865 and 1866)

- Weston Toles

- Tillman Toles

- William Simmons56

- Mat Haggins

- Lewis Wilkinson (some Wilkinsons also live with Henrietta Wood in 1870)

- George Washington

Lessee of Tennessee Penitentiary

On the Tennessee penitentiary, see crowe1956, mancini1996, gossett1992.

In 1866, Ward sold his home near Versailles—100 acres of land for $250 per acre.57 He then moved to Nashville.

There he joined in a business partnership with the lessees of the Tennessee state penitentiary. A furniture making firm, Hyatt and Briggs, had been awarded the lease of the Tennessee penitentiary in July 1866.58

Ward joined the firm sometime in the first half of 1867. But the firm was reconstituted in July 1867, shortly after a destructive fire in the prison, as “Ward and Briggs.”59

Ward produced hemp bagging at the penitentiary during his time as lessee.60

Conflict between the lessees and the state quickly developed over:

- Who was responsible for paying expenses for a fire that destroyed a great deal of machinery in July 1867.61

- Charges by the Warden, Thomas McElwee, that the lessees punished convicts inhumanely, by whipping with the leather strap, simply for failure to meet their daily tasks, and often due to overworking. Those charges led Ward and Briggs to start a smear campaign against the warden that ultimately led to his suspension.62

Ward and Briggs wanted to leverage these conflicts into winning total control over the prison. There was a new penitentiary bill proposed in 1868 that would give entire control of the penitentiary to Ward and Briggs. But it apparently failed.63 Conflicts between the state and the lessees continued, with various state legislators offering resolutions either to cancel the contract or submit the conflicts to arbitration.64

The lease finally ended in July 1869, a year before it was supposed to expire.65 There was subsequent controversy about bonds that were issued by the state to repay the lessees after a settlement over the expenses made to improve the prison.66

A Nashville paper defended Ward from charges made against him in the Twenty-Fourth Annual Report of the New York Prison Association concerning his management of the Tennessee prison.67

While in Tennessee, Ward supported the so-called “Law and Order” movement in Tennessee, which drew together former Confederate generals who argued that the state should not take extraordinary measures (like calling out the militia) to suppress the violent disorder in the state, much of it perpetrated by veterans. The Generals also protested their disfranchisement. At one meeting to discuss these matters, the “entire party accompanied Col. Zeb. Ward to his residence where, over the social glass, they renewed the pledges of moderation and good faith that had been exchanged at the Capitol.”68

After the expiration of the penitentiary lease, Ward moved to Lexington, Kentucky “and operated a steam bagging factory until the fall of 1872, when he came to Arkansas.”69

Lessee of Arkansas Penitentiary

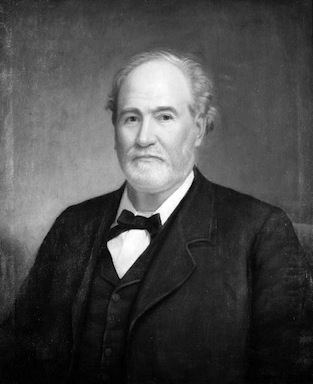

Portrait of Zeb Ward, from Encyclopedia of Arkansas

Beginning in November 1873, Ward was a partner of John Peck, who began leasing the labor of convicts at the Arkansas penitentiary in May 1873. Peck then transferred his lease to Ward on February 5, 1875.70

In the 1880 census, a 57-year-old Zeb Ward is listed as a “contractor for penitentiary” in Little Rock, Arkansas.

According to an entry by Carl Moneyhon in the Encyclopedia of Arkansas:

In 1873, as Reconstruction came to an end, the state legislature revised its program of prison leases and ended payments made to the lessee to support the prisoners. That year’s contract with John M. Peck and his silent partner, Colonel Zebulon Ward, leased prisoners to Peck and required that the lessee furnish labor, food, clothing, and housing for them. The state was to have no expenses. In 1875, Ward bought out Peck and held the prison contract until 1883. Ward profited greatly from his contract, benefitting from the rapid increase in the state’s prison population from 1876 to 1882 after the legislature’s passage in 1875 of a law that made the theft of any property worth two dollars or more punishable by one to five years of imprisonment. Ward also received the contract to build a major expansion of the state prison, using convict labor.

On the lease system in Arkansas generally, see zimmerman1949, Garland Bayliss, and Calvin Ledbetter.

See letters from Ward included in George Washington Cable’s, The Silent South, which criticized his management. (Also available on HathiTrust.

Those letters were cited in critical article on convict lease system in New York Globe in 1884.71

See the 1875 report on Ward’s management of the penitentiary, which was sparked by articles published in the Evening Star by Daniel O’Sullivan.72 According to an issue of the Evening Star, Ward’s “theory in the management of a prison is that he cannot be too hard on thieves, murderers, and such scoundrels unless he cripples and kills them, and so far as hard work is concerned he gives them all they can bear.”73

Amidst popular opposition to Ward’s management of the penitentiary in early 1876 because of the competition of free laborers with convicts, the Daily Arkansas Gazette came to his defense.74

An expose article in the Chicago Inter Ocean connected Ward’s management of the Little Rock penitentiary, and the spread of convict leasing more generally, back to Ward’s management of the Kentucky penitentiary and the testimony of Calvin Fairbank.75

According to gilmore1930, 28, drawing on interviews conducted in 1930:

Col. Zeb Ward and Will Ward, a son, were characterized as mean men. Will Ward was spoken of as a drinker, and a whipper. Zeb Ward seemed to have had power to do anything in Arkansas. He was able to manage the courts, the railroads, and a large percent of the business men.

Ward apparently was a friend of the Arkansas governor and former Confederate Augustus H. Garland.76

See testimony before the Senate about Ward’s management of the penitentiary.

In 1877, a Cincinnati Enquirer special correspondent depicted Ward as a skillful lobbyist who won penitentiary contracts from the state by wining and dining state legislators with mixed drinks:

He came down here four years ago, and contracted with the State to take her Penitentiary and convicts off of her hands, and run the thing without any expense to the State. The Legislature of two years ago made the stealing of two dollars grand larceny. Now, petty stealing has been quite common among the negroes, and, as a consequence, Mr. Ward has his prison “chuck” full, and has had to open two large plantations to employ the surplus upon, but, by close management, is making money out of both of them.77

For an article mocking victims of Arkansas’s “hog law” after end of Reconstruction, see Arkansas Gazette, April 29, 1885, p. 4: “Several sable sons of Afric’s sunny clime were very summarily sent up at the last term of court to abide awhile with Zeb Ward. This perhaps explains why these quondam encroachers upon the rights of the hog have come to the conclusion that even a hog has rights to be respected.”

A description of the convicts on Ward’s plantations appeared in a Kansas newspaper in 1875:

Leaving the town and going up the river bottom we traveled a long distance amidst a succession of cotton and corn fields cultivated by penitentiary convicts under the management of Mr. Zeb Ward, formerly of Kentucky, but now lessee of the Arkansas penitentiary. We met a large gang of convicts coming in from their work of cotton picking. They were heavily guarded by armed men on horseback, and with two or three exceptions the convicts were negroes selected because they were accustomed to the work. In their striped clothes, they formed an unpleasant feature in the landscape, but the penitentiary of Arkansas is a small affair, and outside labor is a necessity. The plantation seemed in a high state of cultivation … Mr. Ward himself led us into a perfect jungle of cotton, covering all the ground, much of it rising several feet above the head of a six-footer who was present.78

Arkansas Gazette frequently printed little notices about county sheriffs bringing boarders to Ward’s hotel (convicts to the prison) to “receive moral culture at the hands of Col. Zeb Ward” or to “receive careful training.”79

A former convict (or penitentiary guard?) J. D. Massey died after being assaulted by Ward while he was lessee of the penitentiary, and his executor J. W. Blackwell, recovered $1,800 from Ward in Faulkner County Circuit Court.80

Bill for the relief of Zeb Ward passed by U. S. Congress, to reimburse him for money he had contracted to receive for housing U.S. prisoners from Louisiana after a scandal there.

A critic of convict leasing published in the Arkansas Gazette in February 1879 advocated the whipping post instead of long sentences: “Here in Arkansas it is a disgrace to humanity—over or about one thousand convicts working out and making cotton bales for Col. Zeb Ward, by far the most wealthy man in all Arkansas, and doing all kinds of work for him; working out and keeping honest workingmen and mechanics from getting any employment at all …”81

Arkansas Businessman and Planter

After his lease of the penitentiary ended, Ward engaged in a variety of business enterprises in Little Rock and cultivated cotton and other crops on plantations near the city.

Plantations

His obituary noted that “he owned large plantations in Pulaski and Conway counties and took a great interest in raising fine stock.”82 He was a founding president of the Arkansas Agricultural Association in 1885.

- “Cotton worms struck Col. Zeb Ward’s Morrilton place two days ago and the latest reports say there is hardly a leaf left. The plantation is a large one and it took a great army of worms to devour the leaves in such short order.”83

Ward continued to use leased convicts and African American laborers brought from other parts of the South to work on his plantations in Pulaski County and Morrilton (Conway County).84

- In February 1894, county officials brought “fifty-five county convicts and placed them in the State Penitentiary for safe-keeping, where they will likely remain until March 17, when bids for their leasing will be received and if not leased out, they will likely be placed on the county roads.” The convicts were found half naked and “half starved.” There were also ugly rumors being spread about racial conflict at the camp, where “Contractor Ward’s contract” had been revoked on February 3. “Mr. Ward’s friends say they belief he did the best he could under the circumstances and is incapable of treating prisoners badly,” but unclear if this is referring to Ward or Ward Jr.85

- A “notorious negro burglar” named Charles Brown escaped from “Col. Ward’s plantation” in 1894 while “pulling fodder” there. He was fired at by a guard, who missed.86

- Ward’s plantation “three miles up the river” and consisting “of about 400 acres” had been rented by the Penitentiary Board for working convicts earlier that year.87

- Another “colored farm hand” on Ward’s plantation named Bolton Hughes was badly hurt in a wind storm in 1894.88

- “Seventy-five negroes passed through the city from South Carolina, yesterday, on their way to Zeb Ward’s plantation, near Morrilton, in charge of R. A. Williams, passenger agent of the Memphis and Little Rock road.” (Williams is aka Peg Leg Williams.)89 An earlier article names Ward as the “chief engineer of this negro emigration.”90

- Re: his son: “Mr. Zeb Ward, Jr., is here [in Pine Bluff] getting, we understand, a large number of negro farm hands to take to his plantation above Little Rock.”91

Other Businesses

- He was a stockholder in a hot springs company

- Winner of a contract to build a railroad from Little Rock to Pine Bluff using convict labor92

- Ward wrote a letter to the editor of the Arkansas Gazette in 1888 advocating that convict labor be used to manufacture jute cotton bagging.93

- A founding owner of Little Rock Oil Mills and Cotton Compress in 188094

- President of the Little Rock and Mississippi Railroad95

- Ward was eventually a director of the Gazette Publishing Company in Little Rock, and was described there as “Zebulon Ward, capitalist”

- There was a large lawsuit between Ward and the city of Louisville over some paving stone provided to the city by Ward that eventually was decided in Ward’s favor not long after his death96

- Praised for having helped clean up Little Rock during a yellow fever panic without being asked for payment: “No state in the Union has a better citizen than Zeb Ward. he has done more for Little Rock than any other man.”97

- Entertained a group of Memphis editors in June 1879 and impressed one journalist as “a stately representative of the Blue Grass region.”98 Likewise entertained a group of wealthy investors from other states to Little Rock.99

Ward owned a controlling interest in one of the first municipal waterworks companies in Arkansas, as well as Mountain Valley Water Company The new water works was opened for the first time in early November 1887, but a disaster befell the waterworks in the fall of 1887.100 For a description of the water works see Little Rock Arkansas Democrat, October 26, 1887, p. 1, available on Newspapers.com.

Labor strife at the waterworks: “A number of men employed by Col. Zeb Ward on his reservoir struck for higher wages yesterday, and he has hired forty men from the penitentiary to go to work next Monday.”101 An earlier article reports a strike “among some colored laborers employed by Col. Zeb Ward on a ditch being dug for water mains. … Their work was nearly finished and they were not employed again.”102

Horse Racing

Map showing location of Ward’s horse farm in Versailles, clipped from topographical map by E. A. and G. W. Hewitt (1861)

Ward was a lifelong “man of the turf” who became well known nationally as a colorful figure in the horse-racing and thoroughbred-breeding world. His taste for horse racing appears to have dated back to the 1850s and the 1860s, and it continued during the Civil War and into 1872.

He was connected with the racing horse trader Henry Price McGrath and a member of the Kentucky Association, and he took a horse to a race in Massachusetts in 1862.103

An obituary noted that he was “well known on the turf, although none of his horses were especially famous.”104

From Katherine Mooney, in email dated April 28, 2015:

As far as how deeply he was into Thoroughbreds, it was pretty deep–his connection to Price McGrath is significant, since McGrath owned the first Kentucky Derby winner. Ward also owned a great horse named Tipperary, who was part of this sort of three-way duel for supremacy throughout 1864–and he took that horse everywhere to run him, including Saratoga and Monmouth Park in New Jersey. (The jockey was Abe Hawkins, who was a former slave.) In terms of how much money he made out of it, I’m not sure. It was possible for some people to make money off it, but usually not people who were doing it on any large scale. I never quite figured out how/if he was related to the Ward Brothers of Lexington–Junius Ward was the elder–who were shareholders in the Metairie Course at New Orleans in the 1850s, which was the biggest, glitziest racetrack in America. The other shareholders were bigtime Louisiana and Mississippi planters, so that meant major money. I’ve got a map indicating his farm was on Big Sink Road near Versailles, which was then and is now where the seriously fancy farms are. Obviously not every single one is a huge operation, but nobody around there was hurting. To give some context on values, Ward’s neighbor Robert Alexander paid $15,000 in 1855 for the racehorse Lexington, expecting to turn him into a breeding stallion. People at the time thought that was a good bit of money to pay for a horse (which, translated to today’s dollar values, it was, but, given what people pay for Thoroughbreds now, not much has changed.)

Unfortunately, I don’t think the match race was what brought him back to Kentucky–it actually took place in New Jersey, though Ward was a big fan of the Kentucky horse involved, John Harper’s Longfellow, and he was the major correspondent about the race in the Spirit of the Times (where he vindicated the performance of John Sample, Longfellow’s black jockey.) (That’s “The Saratoga Cup,” Spirit of the Times 14 Sept 1872, 65.)105 Harper was one of Ward’s neighbors, and at the time of the race, he’d just been involved in a lynching–the best account of that and of a lot of this period in that part of Kentucky is MaryJean Wall’s How Kentucky Became Southern, which I highly recommend.

For more see wall2010; mooney2014.

1850s

- “Mr. Zeb. Ward, of Woodford, has sold his brown gelding, that took the first premium at the recent State Fair, in the single harness ring, to a gentleman in the South, for $1,000.”106

1860s

In 1860, Ward purchased one of the fillies imported from England under the auspices of the Kentucky Importing Company. The horse, Salorta, was stolen during the Civil War.107

One of his big early successes was from the horse Sailor, by Yorkshire, who came in third in the 1861 Challenge Vase at Woodlawn in Louisville, beating out Bettie Ward, by Lexington, in the fastest four-mile heat ever run in Kentucky.108

In a June 7, 1862, article in Wilkes’ Spirit of the Times vol. 6, no. 14, p. 217, Wilkes announces that Ward plans to bring numerous entries to an upcoming “New York Turf meeting,” some colts to sell as saddle horses, as well as the thoroughbred stallion Sailor, which he plans to put out to stud for owners of mares in the area who would like to try for a thoroughbred colts. A subsequent, June 21, 1862, article in the paper (vol. 6, no. 16, p. 249), announces the arrival of “the great racers of Kentucky,” including “Captain Moore and Hon. Zeb. Ward, with their magnificent strings of race horses.” Ward has brought “Sailor, by Yorkshire, who beat Bettie Ward in the great four-mile race for the Challenge Vase at Louisville, when Mollie Jackson won it; Reporter, a noted winner, by Lexington, out of an Eclipse mare; Pope Swigert; Blondin, by Lexington, out of a Glencoe mare, in the three-year-old stakes; and a filly by Lexington, in the stake, play or pay, at New York.”109

One of his horses was Mollie Hambleton, born in 1862.

Ward was reportedly “the only turfman in America who ever won a racing stake by a start in which all the horses but his stood still at the post and his filly went on and won. This actually occurred at Suffolk Park Course, Philadelphia, in June, 1863, and Ward’s filly got the stakes, some $1,200, together with the bets.”110

Ward was briefly rumored to have died in 1864, as reported by a sporting magazine in New York who described him as “a very honorable and enterprising supporter of the turf”

Ward appears in a detailed account of the Kentucky horse district in the March 29, 1862, issue of Spirit of the Times. The article is available in the AAS Periodical Series on EBSCOHost (where I got several other hits by searching for Ward that I need to investigate further). In the March 29 article, George Wilkes, the editor of the Spirit of the Times, wrote a letter back to his paper describing his visit to Cincinnati and then to Frankfort, where he hired a buggy on March 15 to make “a journey of fourteen miles to the residence of Hon. Zeb Ward, at Versailles”:

I was for the first time in what I had known by story as the blue grass region, where everything in nature thrives, and where man himself culminates in physical perfection with the descendant of the barb. On all sides I beheld a beautiful rolling country, dotted with browsing stock, and already covered with a verdure not due to our more northern pastures for a month to come. This was the blue grass, whose closely matted roots harbor a warmth that responds instantly to the first touch of spring; and which indeed, retains at all times so large a vitality and such liberal excess that it will support stock during the entire winter. …

They say that the hospitality of the people of Kentucky ruins the business of the taverns. I found two proofs of the maxim, in the absence of a single roadside inn between Frankfort and Versailles, and in the determined refusal of Mr. Ward to permit my carpet-bag to go to the hotel of his town. A snug corner of his fine mansion, therefore, gave me quarters for the night, while an abundant supper and some two or three draughts of genial old Bourbon sent me tranquilly to bed.

The storm still prevailed in the morning, but time was so precious with me as to put weather at a discount; so Mr. Ward ordered up his top-buggy, and placing a little nigger behind in order that he might open gates and let down the bars, we started out for an interior drive among the racing farms of Woodford county. On our way across the fields of his own estate, a broad stretch of over six hundred acres, all in use, Mr. Ward directed my attention to a lot of yearling colts and fillies, which came to his whistle in a corner of the pasture. The two of these which he prized most highly were a bay filly by Lexington, dam by Glencoe, out of Eudora; and a bay filly by Scythian out of Cottage Girl, by Ainderby. The Lexington filly, however, was the object of his especial pride, and he confidently looks forward toward a career of distinction for her on the turf.

Wilkes also visited Ward’s stables, which appear to have been maintained by a Mr. Clinton, as well as the much larger neighboring estate of Robert Alexander (see Alexander Family Papers).

1880s

There appears to have been a horse named after Ward in the 1888 Kentucky Derby; see chew1974, p. 276

General Descriptions

A description of him during his trip to New York in 1888:

Although he has only been at the St. James a few days he has already become well known to the frequenters of that and other resorts, and he is usually surrounded by a crowd, who delight in listening to his stories. He has the reputation of being the most unique raconteur south of the Mason and Dixon line.111

Another such description, reprinted from the New York World:

An iron-gray beard surrounds the bronzed features of a gigantic Kentuckian, whose sparkling eyes have been for a day or two taking their first peep at New York for years. People whom he has never seen and never will see recognize him as soon the name “Col. Zeb Ward, the richest man in Arkansaw,” is mentioned. He is a splendid specimen of a vanishing type, the country-bred American horseman. His 240 pounds of weight are admirably carried off by his height, which is more than six feet two. He is the owner of plantations, water works and oil mills, and his seventy-two years don’t keep him from engaging in many other enterprises. Col. Ward was an intimate friend of old John Harper and Henry Price McGrath, the Nestors of the race track. … Laywer Charley Brooke and Stuart Robson declare themselves fascinated by Col. Ward’s old-school eloquence.112

Described by the New York Times in 1862: “well-known in Kentucky and the adjacent country as a lover and patron of the delights and excitements of ‘The Turf.’”113

Physical

- From obituary in Louisville Courier Journal: “Col. Ward was an impressive looking man, full six feet high, with broad shoulders, crowned with a massive head and a strong, shrewd face.”114

- From ward1961, p. 67: “He is described as a very handsome man, one of the tall Wards.”

- The fact that Ward looked like Grant was often mentioned in the press about him.115 He was also said to resemble Senator James B. Beck of Kentucky.116

- “The typical Southerner, middle-aged, with low-crowned, wide-brimmed, soft, white hat, who has attracted so much attention at the quarter-stretch, is Zeb Ward, a wealthy Arkansas planter and enthusiastic admirer of thorough-breds.”117

Business Acumen

- From gilmore1930: “He was one of the most influential citizens of Arkansas. He … would pursue most any activity which would bring him financial returns.”^[gilmore1930, 18. Gilmore often references an article, potentially an obituary, about Ward from Louisville Evening Post, October 22, 1890. May have this at the Filson.

- From ward1961, p. 67: “His career was a fantastic one as everything he touched seemed to turn to gold. His great wealth was not only the result of his tremendous business ability but also his personal charm and his gift of getting along with everyone he met.”

- From obituary in Louisville Courier Journal: “He left the reputation in Kentucky of a bold and successful speculator as well as a business man of quick and accurate judgment.” Also tells a story about Ward puchasing a wagon-load of hoop-poles on the road, as illustrative of his risk-taking. “By his bold speculative nature he made and lost half a dozen fortunes, leaving the State [of Kentucky] about 1868 practically bankrupt,” but then “soon amassed another fortune” in Arkansas.“118

Miscellaneous

- “‘Think I’ve seen you before,’ patronizingly remarked a party to Col. Zeb Ward yesterday. ‘Yes,’ said the colonel, looking him in the eye, ‘I’ve kept three penitentiaries in my time.’”119

- Another example of Ward as raconteur: “Bad Day for Packing Ham: Col. Zeb Ward Perpetrates a Pun on Col. B. D. Williams,” Arkansas Gazette, January 8, 1890, p. 7.]

- A hotel blotter in New York World for December 9, 1887, says Ward, “a well-known Westerner from Little Rock,” was staying at the St. James Hotel.120 (Perhaps after the Saratoga races?)

- “We were yesterday, shown, by Zeb. Ward, Esq., Secretary of the Turf Congress, a magnificent gold mounted riding whip, of exquisite workmanship. … It is intended as a prize to the best rider at the race to be held under the auspices of the Turf Congress at Memphis on Friday the 22d inst.” (Ward was Secretary of the Turf Congress.)121

A brief article in New York Sportsman, January 21, 1888, p. 63, refers to Wood v. Ward:

Colonel Zeb Ward of Little Rock, Ark., who left this city last week for home, thinks that he was the last man to pay for a negro slave in this country. A negro woman who had been in his possession for several years, while a suit regarding her ownership was pending, afterwards brought suit against him for services and gained a verdict. When Colonel Ward made out a check he worded it: “To pay for the last negro that will ever be paid for in this country.”122

- Humorist Opie Read remembered Ward being present when a deputation of “negroes” in Little Rock came to shake hands with Ulysses S. Grant, and that one of the deputation recognized Ward as the lessee of the penitentiary and “drew back.”123

- Ward claimed to have admired Grant and voted for him in 1868124

- A Zeb Ward building was built in Little Rock in 1881

- A report in a New York newspaper alleged that Ward one a row of brick buildings in Little Rock in a “stiff game of poker” with a Colonel Oliver.125

- Ward’s Little Rock house is now occupied by a law firm that keeps a brief biography of him online; see also notice about the Ward-Heiskill house sale

- There may be an article about Ward in Woodford Sun newspaper, May 21, 1896, according to notes kept at the Woodford County Historical Society

- “Col. Zeb Ward returned Sunday from the Chicago convention.”126

- One of the WPA interviews, with Mary Jones, recalled her mother as having worked for Ward: “After freedom, when the old folks died out, she cooked for Zeb Ward—you know him, head of the penitentiary”

- Look for a WPA narrative collected on August 22, 1936, by WPA interviewer J. C. W. Smith from John Wade, Little Rock man, which tells a “Zeb Ward” ghost story according to Alan Brown, Shadows and Cypress

- His son, Zeb Ward, Jr., participated in a welcoming parade for President Harrison.

- On Ward’s Kentucky background, see this genealogical chapter.

- Did he own land in Ohio, perhaps given him by his father or great-uncle? See ward1961.

- “Colonel Zeb Ward lost between 400 and 500 acres of cotton by the recent overflow. As soon as the waters retired, the colonel had the ground plowed up and planted in corn and peas. The corn is now half a leg high, and has been worked over once.”127

- Involved in Democratic Party politics and sat on several national committees or conventions after the Civil War (see coverage in summer of 1880, e.g.)

- “Zeb Ward, an aged and wealthy citizen of Arkansas, hailing from Little Rock, is in the city. Mr. Ward has a valet with him—a sprightly, good-looking colored chap, who looks out for his master’s interests carefully and intelligently. Although well along in years, Mr. Ward is a theater-goer, and he keeps in close touch with the times by a careful daily reading of the Republic.”128

R. G. Dunn and Company Credit Report Volumes

See spreadsheet for Ryan Shaver’s transcriptions. Highlights:

- From 1876: Reports on his $125,000 contract with Arkansas and his use of convict labor. “Got broke up in Ky. Is now building himself up again. paid all obligs. promptly, is a hard worker and stands good with this community.” Later notation in 1878 says he “Is earning money owns fine R.E. [real estate] pays promptly. highly regd. + safe for everything worth at least 150 m$ [$150,000] + in time will be worth nearly double that amt.129

- From Kentucky volumes: “good cr. [credit] was wealthy at onetime. est. his wor. [established his worth] If any transactions, have them well defined.”130

- From 1859: “Is a farmer on a lar. scale in Woodford Co. Has made a f. deal of money as keeper of the penitentiary.” Much longer discussion of his wealth and partnership with a man named “Robb” in the Woodford County volume, which describes his holdings in February 1862: “581 acres $32536, lots 2 m$, 24 slaves 96 c$, horses 44 c$.”131

- From 1867-1869: entries on his prison lease in Tennessee, including his litigation against state.132

To-Do List

- qq Go through probate records on Ancestry

See ward1961, 60; lafferty1945, 9, which says the birthdate was recorded in the “Ward Family Bible”; gilmore1930.↩

See also this related marriage record.↩

“Glimpses of Yesterday,” Arkansas Gazette, June 9, 1940. See also “Busy Life Ended,” Arkansas Gazette, December 29, 1894; “Colonel Zeb Ward,” Chicago Inter Ocean, December 29, 1894.↩

“Glimpses of Yesterday,” Arkansas Gazette, June 9, 1940.↩

Married Miss Mamie Logan, of Hyde Park, at her brother’s house in Hyde Park, Mr. E. S. Sibley, in Chicago. See Chicago Inter Ocean, December 20, 1882, p. 5. Ward Sr. attended the wedding. See Arkansas Gazette, December 24, 1882, p. 5. A “Zeb Ward” is listed as a “contractor” in a book of members of the Arkansas Board of Trade in 1901, which must be Junior.↩

See Ancestry.com.↩

See lafferty1945; ward1961, p. 62.↩

The 1830 census shows nine white persons and no slaves in Andrew Ward’s household. The 1840 census for Harrison County lists Andrew Ward with six white persons and no slaves.↩

See lafferty1945. The marriage record for Andrew and Elizabeth Ward shows her father’s name. Zebulon Headington’s will is in Harrison County Will Book D, p. 465-468, KDLA, and shows the inventory of his estate in October 1841, which includes three named slaves (Augustus, Cynthia, and Kate—possibly a family) valued at a total of $1350. I could not locate Andrew Ward in the will book, despite searching in Will Books C through F. The 1830 census also shows that Headington had five slaves. In the 1840 census for Harrison County, he is listed with four enslaved people.↩

See lafferty1945 for more details.↩

lafferty1945, 75-75.↩

“River News,” New Orleans Times, November 6, 1874, available on AHN: the notice also reported that a fire at Ward’s cotton gin, “three miles above Little Rock,” had recently burned at a loss of $8,000 with $1,900 insurance. Markland was probably Absalom Hanks Markland.↩

“Busy Life Ended: Col. Zeb Ward Passes Away at His Home in This City,” Arkansas Gazette, December 29, 1894. Much of this is repeated without attribution in “Glimpses of Yesterday,” Arkansas Gazette, June 9, 1940, but it adds that he was in California for two years.↩

See ward1960, family history by Helen Ward Lafferty Nisbet, held at the Kentucky Historical Society in Frankfort, link.↩

Looked at these rolls at Kentucky Department of Libraries and Archives.↩

“Arrivals at the Principal Hotels,” Louisville Daily Courier, December 31, 1846; “List of Letters,” “List of Letters,” July 3, 1848, available on Newspapers.com.↩

See “War Veterans: Heroes of the Mexican War Meet and Celebrate,” Little Rock Arkansas Democrat, February 24, 1880, available on Newspapers.com; “Meeting of Mexican War Veterans,” Little Rock Daily Arkansas Gazette, June 20, 1878, available on Newspapers.com.↩

Based on footnotes in Damon Eubank, The Response to Kentucky to the Mexican War, 1846-1848 (Lewiston: Edwin Mellen Press, 2004), I tried James A. Ramage article in Register of the Kentucky Historical Scoiety 81 (1983) [9/22: no mention of Ward in the article, though it does mention a speech by “prominent attorney” George B. Kinkead welcoming returning veterans]; Salisbury article in Filson Club Historical Quarterly 61 (1987); Sam Hill, Report of the Adjutant General of the State of Kentucky, Mexican War Veterans (Frankfort, 1889) [found no reference to Ward in this book, which I examined at Kentucky Historical Society]; and Works Progress Administration, Military History of Kentucky [which indicates on p. 136 that a company of infantry formed in Harrison County was organized but not accepted into service because the requisite regiments had already formed]. But since Ward doesn’t show up in Fold3 for the Mexican War, it’s likely this is a legend.↩

Kenton County Court Order Books, 1853-1854, Kentucky Department of Library and Archives, Reel 551072. I couldn’t find anything about Ward in the previous order books on the previous reel, though I was relying largely on indices at the beginning of the book and quick skims of pages around the start of terms.↩

Covington Journal, April 23, 1853, p. 2.↩

See Kenton County Tax Assessment Rolls, Microfilm 008091, Kentucky Department of Libraries and Archives.↩

“Important Arrest,” Covington Journal, June 11, 1853.↩

“Stampede of Slaves.–Arrest of the Fugitives,” Covington Journal, June 17, 1854, p.2, col. 3, which identifies him as “Deputy Sheriff Ward”; “Nine Fugitive Slaves,” June 22, 1854, St. Albans (Vermont) Messenger, p. 3. See also the reference to this arrest in a clipping in Thomas Foraker Scrapbook. The slaves had escaped from Boone County and were defended by John Jolliffe.↩

See Kinkead’s memoir, dated August 21, 1921, in June Lee Mefford Kinkead, Our Kentucky Pioneer Ancestry: A History of the Kinkead and McDowell Families of Kentucky (Baltimore: Gateway Press, Inc., 1992), 252-253.↩

See Franklin County Tax Assessment Rolls, Microfilm 007980, Kentucky Department of Library and Archives.↩

For more on Wines and Dwight, see mclennan2008.↩

E. C. Wines and Theodore W. Dwight, Report on the prisons and reformatories of the United States and Canada, made to the Legislature of New York, January, 1867 (Albany: Van Benthuysen & sons, 1867), 260.↩

William C. Sneed, A report on the history and mode of management of the Kentucky Penitentiary from its origin, in 1798, to March 1, 1860 (Frankfort, Ky.: State of Kentucky, 1860), 514-516. Ward displaced the incumbent keeper, Newton Craig, by a final vote of 75 to 60.↩

“Keeper of the Penitentiary,” Covington Journal, February 25, 1854.↩

I made photocopies of these reels.↩

Louisville Daily Courier, February 9, 1858, p. 3.↩

See deed of property from John M. Coleman to Zeb Ward, Woodford County Deed Book W, p. 394. Also see the April 1859 sale of the store in Versailles operated by Ward and Robb, in Deed of Property by H. H. Culbertson to Zeb Ward, Woodford County Deed Book W, p. 488.↩

Deed of Property from H. H. Bohannon to Zeb Ward, Woodford County Deed Book X, p. 197.↩

One of these deed transfers was witnessed by Charles Mynn Thruston. See Deed from John B. Kinkead to Zeb Ward, Woodford County Deed Book X, pp. 367-368. Other entries in Book Y include pp. 85, 89, 127, 188, 216, 231, 239, 390 (the “Shelton House” in Versailles outside the courthouse, bought at auction), and 577. One of these shows that he was briefly a trustee at Woodford Female College.↩

See Woodford County Circuit Court Case File Index, Microfilm 7036112, KDLA. He appears in the index to this book, and also in BB, CC, DD, though I didn’t look at the specific pages discussing the suits, as the order books are unlikely to yield very much information about what happened in the cases. The general index also says he appears in Book Z on p. 187, but I could not find that reference.↩

Woodford County Court Order Book L, p. 258. Ward later contested some of these valuations: see p. 318. The assessment says that among his 15 slaves, 10 were over 16.↩

“Stealing Asteroid,” New York Sun, February 12, 1888.↩

Coverage also in “Morgan at Versailles,” Philadelphia Inquirer, July 24, 1862.↩

“Important Decision,” Louisville Daily Courier, October 16, 1866, p. 1. For the appeals case, see Bush’s Reports, vol. 2, 606.↩

W. E. Railey, “Woodford County,” Register of the Kentucky Historical Society 18, no. 53 (1920), 64; “The Ward Family,” Register of the Kentucky Historical Society 6 (1908), 38.↩

“Covington,” Cincinnati Daily Commercial, July 16, 1861, p. 2.↩

Quotes from whartonwilliams1986, pp. 32 (1860 entry), 80 (1862 entry).↩

“By the Orange Train,” Houston Tri-Weekly Telegraph, March 6, 1863 (quote).↩

“Kentucky Legislature,” St. Louis Daily Missouri Democrat, January 31, 1863, p. 1. Also “Kentucky Legislature” in Maysville, Ky. Weekly Bulletin, February 5, 1863, link: “Mr. Ward offered an amendment, providing that the Legislature of Kentucky does not expect any of her soldiers, provided for by this bill, nor any that are now in the field, to aid in enforcing the unconstitutional proclamation of the President, of the 1st of January, 1863, nor any proclamation that he may issue, the enforcement of which would make our soldiers commit an act which would be felony by the laws of our own State, but to fight for the sole object of putting down the rebellion.” The House Journal mentions Ward’s moving an amendment but does not contain the text.↩

“Busy Life Ended,” Arkansas Gazette, December 29, 1894.↩

See draft registration record on Ancestry.com, in my “Shoebox.”↩

Also an Arthur Simmons from Louisville in the USCT, and later in school for the blind. There are multiple records for William Simmons in the 116 USCI on Fold3, and they imply that he remained enlisted until January 1867 when mustered out in New Orleans.↩

“Sold,” Louisville Daily Courier, December 10, 1866. See his detailed advertisement for this and a much larger set of farms in “Woodford County Farm for Sale,” Louisville Daily Courier, August 22, 1866.↩

Briggs was a native of Kentucky, a lawyer born and raised in Warren County, and had perhaps only recently moved to Tennessee, too. See “Nashville,” Louisville Daily Courier, July 17, 1866, p. 4; letter from C.M Briggs to Beriah Magoffin, March 26, 1861, Civil War Governors of Kentucky.↩

“Dissolution of Partnership,” Nashville Union and American, August 3, 1867, p. 2. The notice says that the firm was “Hyatt, Briggs & Ward,” so Ward must have joined the firm between the time of the lease and the fire: an ad from June 1867 advertising the wares of the penitentiary workshop has all three men as subscribers. “Nashville Agricultural Works,” Nashville Union and American, June 18, 1867, p. 1. The change must have been made between December 1866 and then, based on the 1867 penitentiary report, dated October 1, 1867, which reported that Ward had bought out Hyatt’s interest in the firm. The same ad for the “Nashville Agricultural Works” appeared in March 1867 (placed in January) with “Hyatt, Briggs & Moore” as the operators. See Nashville Tennessean, March 13, 1867, p. 3. A reference to “Hyatt, Briggs & Ward” appears in an ad from May 1867. Ad for Southern Insurance Company, Pulaski Citizen, May 3, 1867, p. 3.↩

See add in Nashville Tennesseean, September 29, 1867, p. 3.↩

The August 1868 report of the Directors of the Penitentiary detailed disagreements between the state and Ward & Briggs regarding the expenses of rebuilding the prison workshops after the June 22, 1867, fire. The lessees had refused to pay the state for the lease of the convicts since that date to January 1, 1868, “claiming that it ought to be applied in discharge of their loss in materials, machinery, &c.” The conflict was partly caused by a discrepancy between the accounts kept by the warden and the lessees.↩

On the conflict over treatment and with the warden, see “The Penitentiary: A Wordy War between the Lessees and Warden,” Nashville Tennessean, September 5, 1868; 1868 Annual Report of the New York Prison Association, pp. 137ff. See also pp. 75-79, 102, of Tennessee. General Assembly. House of Representatives. House journal of the … session of the … General Assembly of the state of Tennessee. A.D. 1868. Nashville [Tenn.], 1868. 279pp. Sabin Americana. Gale, Cengage Learning. Fondren Library, Rice University. 22 April 2015 http://galenet.galegroup.com/servlet/Sabin?af=RN&ae=CY3809487245&srchtp=a&ste=14. The report of punishments submitted by the warden also showed that most of the infractions occurred in the hemp factory and often involved failure to do task; a common punishment was suspension by thumbs for 30 to 160 minutes.↩

“The New Penitentiary Bill,” Nashville Union and American, March 10, 1868.↩

See “State Prison: Letter of the Lessees to the Legislature,” Nashville Union and American, December 2, 1868; p. 93, 330, of Tennessee. General Assembly. House of Representatives. House journal of the … session of the … General Assembly of the state of Tennessee. A.D. 1868-69. Nashville [Tenn.], 1868. 520pp. Sabin Americana. Gale, Cengage Learning. Fondren Library, Rice University. 22 April 2015 http://galenet.galegroup.com/servlet/Sabin?af=RN&ae=CY3809487538&srchtp=a&ste=14. Also see Tennessee. General Assembly. Senate. Senate journal of the … session of the … General Assembly of the state of Tennessee. July, 1868. Nashville [Tenn.], 1868. 223pp. Sabin Americana. Gale, Cengage Learning. Fondren Library, Rice University. 22 April 2015 http://galenet.galegroup.com/servlet/Sabin?af=RN&ae=CY3809979412&srchtp=a&ste=14.↩

Tennessee. General Assembly. Senate. Senate journal of the … session of the … General Assembly of the state of Tennessee. November, 1868. Nashville [Tenn.], 1868. 363pp. Sabin Americana. Gale, Cengage Learning. Fondren Library, Rice University. 22 April 2015 http://galenet.galegroup.com/servlet/Sabin?af=RN&ae=CY3809979174&srchtp=a&ste=14.↩

See p. 817ff in Tennessee. General Assembly. House of Representatives. House journal of the … session of the … General Assembly of the state of Tennessee. A.D. 1869. Nashville [Tenn.], 1869. 1512pp. Sabin Americana. Gale, Cengage Learning. Fondren Library, Rice University. 22 April 2015 http://galenet.galegroup.com/servlet/Sabin?af=RN&ae=CY3809819338&srchtp=a&ste=14.↩

“Prison Association of New York,” Nashville Union and American, July 17, 1869, p. 4.↩

“Reconstruction: The Law and Order Movement in Tennessee—Conference between Confederate Generals and the Legislative Military Committee,” New York Tribune, August 5, 1868, p.1. See also “The Peace Conference in Tennessee,” Macon Weekly Telegraph, August 7, 1868.↩

“Glimpses of Yesterday,” Arkansas Gazette, June 9, 1940. In the 1870 census, a 48-year-old Zeb Ward is listed as a hemp manufacturer in Lexington, Kentucky. The value of his real estate was $50,000 and the value of his personal estate was $10,000.↩

According to a later article, he began the lease in the winter of 1872. See “Glimpses of Yesterday,” Arkansas Gazette, June 9, 1940.↩

“Infamies of the Southern Convict Lease System,” New York Globe, February 2, 1884.↩

Report of the Board of Commissioners for the Leasing Management and Regulation of the Arkansas State Penitentiary, on the result of an investigation concerning the treatment of prisoners, and general conduct of the institution. Together with the testimony taken in the course of the investigation. September, 1875 (Little Rock, AK: 1875). May be the same as this book.↩

gilmore1930, 23.↩

See early February 1876 issues of the Gazette.↩

“Southern Prison Horrors,” Chicago Inter Ocean, February 15, 1890, available on Newspapers.com. Another version of this identifies it as work of Albion W. Tourgee: “Sheol! The Terrible Convict System of the South,” Cleveland Gazette, April 12, 1890, p. 1. See also “Worse than Death: The Ills which Afro-American Convicts Endure in the South,” Detroit Plain Dealer, March 14, 1890.↩

Josiah Hazen Shinn, Pioneers and Makers of Arkansas (1908; Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Company, 1967), 324.↩

“Arkansas Letter,” Cincinnati Enquirer, March 13, 1877; see also “State News,” Fort Smith New Era, March 5, 1879, p. 2: “The Legislature has been dined and wined at the Penitentiary by Zeb Ward, its superintendent. There is a legislative investigation pending against the manager of this institution and common decency would have suggested it to be extremely improper, that any members of the Court—for such is the Legislature in this instance—should attend a banquet offered them by the accused.”↩

“The New Arkansas Traveler,” Topeka, Kan., Commonwealth, October 7, 1875.↩

See e.g., March 21, 22, and 24, 1878, issues.↩

“Cost of Killing a Convict,” Marion, Ohio, Marion Star, August 3, 1885, p. 1, available on Newspapers.com; “Local Paragraphs,” Arkansas Gazette, September 17, 1881, p. 4.↩

“The Whipping Post,” Arkansas Gazette, February 9, 1879.↩

“Glimpses of Yesterday,” Arkansas Gazette, June 9, 1940.↩

Little Rock Arkansas Democrat, September 17, 1889, available on Newspapers.com.↩

See “Local Paragraphs,” Arkansas Gazette, January 6, 1885.↩

“Half Naked,” Arkansas Gazette, February 24, 1894. Other articles suggest that the Ward referred to is William H. Ward. See “In the Neck,” Arkansas Gazette, February 4, 1894.↩

“A Bad Convict,” Arkansas Gazette, August 31, 1894, available on Newspapers.com.↩

“Renting a Convict Farm,” Arkansas Gazette, April 25, 1894.↩

“Storm on Ward’s Plantation,” Arkansas Gazette, March 22, 1894.↩

Memphis, Appeal, February 5, 1885, p. 4, Newspapers.com. See also Arkansas Democrat, December 5, 1884, which reports Williams passing through Atlanta with a “party of 250 negro laborers bound for Morrilton, Ark. They will be employed on Zeb Ward’s farm in place of convict labor.”↩

“The Negro Exodus,” Anderson, SC, Intelligencer, December 11, 1884.↩

“Mr. Zeb Ward, Jr.,” Arkansas Gazette, February 25, 1893.↩

See general regional coverage in December 1879, including a critical article on it in Fort Smith New Era, December 17, 1879, p. 3. Also “Little Rock, Mississippi River, and TExas Railroad,” Arkansas Gazette, January 9, 1880, p. 4; “Joined at Last,” Arkansas Gazette, February 26, 1881, p. 4, which reports speech of Ward at ceremony celebrating track completion: “Col. Ward said he was a worker, not a talker, but he had made a speech before, which the Maine men said was a good one, and he would repeat it, ‘Let’s take a drink.’ [Applause.]”↩

“Bagging,” Arkansas Gazette, September 29, 1888.↩

“Glimpses of Yesterday,” Arkansas Gazette, June 9, 1940↩

“Glimpses of Yesterday,” Arkansas Gazette, June 9, 1940↩

“Louisville Gives Up the Lucre,” Arkansas Gazette, February 24, 1895. See also New York times article; “Col. Ward Interviewed,” Arkansas Gazette, June 29, 1889, p. 5, which reprints from Memphis Ledger and describes Ward as “the genial, old whole-souled ‘Rough Diamond’ of Arkansas. … Although 68 years old he is as buoyant as a boy and in energy, good spirits and go-aheadativeness, he is a splendid type of the American citizen and an example for young men of 30, 40 and 50 years of age.”↩

Arkansas Gazette, March 23, 1880, p. 8.↩

“Little Rock Notes,” Memphis Public Ledger, June 6, 1879, p. 2.↩

“Men of Means,” Arkansas Gazette, April 22, 1890, p. 8.↩

“Clear Water,” Little Rock Daily Arkansas Gazette, November 2, 1887, p. 1; “Col. Zeb Ward is in hard luck,” Little Rock Arkansas Democrat, November 3, 1887, which states its confidence that Ward will rebound from “the ruins of a once magnificent property … He never gives up, never loses courage or hope.”↩

Little Rock Daily Arkansas Gazette, June 25, 1886.↩

Little Rock, Daily Arkansas Gazette, March 9, 1886, p. 5.↩

For connection to McGrath, see “Busy Life Ended,” Arkansas Gazette, December 29, 1894.↩

“Col. Zeb Ward,” Louisville Courier Journal, December 30, 1894.↩

“Splendid Geldings,” Cleveland Ohio Farmer, November 19, 1859.↩

William Henry Perrin, ed., History of Fayette County, Kentucky (Chicago: O.L. Baskin, 1882), 160.↩

“Woodlawn Races, First Day,” Louisville Daily Courier, May 20, 1861, on Newspapers.com.↩

Image of articles sent to me by Cathy Schenck.↩

Louisville Courier-Journal, January 17, 1888, p. 4, which also reports that Ward had just left Louisville for his Arkansas home the previous Saturday and described him as “the famous Kentuckian, now of Arkansas.” A longer version of this story, in which Ward explained to a reporter that his horse was the only one who had heard the starting drum, and that when Ward realized it, he raced out onto the track and told the jockey to finish the race: “He Hit the Drum, and That Settled the Race in a Walk Round,” Cincinnati Post, January 6, 1893, p. 3.↩

“The Last Slave Buyer,” Wilmington, Ohio, Journal, February 1, 1888. On the St. James social scene, see New York City Guide (New York: Random House, 1939), 207; 2015 blog post by Tom Miller; “St. James Hotel,” in Encyclopedia of New York City, ed. Kenneth T. Jackson, second edition (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010), 1139.↩

“Col. Zeb Ward,” Louisville Courier-Journal, December 14, 1887, p. 5↩

“The Races on the Union Course,” New York Times, July 6, 1862, link.↩

“Col. Zeb Ward,” Louisville Courier Journal, December 30, 1894.p.3, available on Newspapers.com.↩

See Ottawa Illinois Free Trader, February 9, 1889, p. 6; “Great Men’s Doubles: Stories about Resemblances that Cause Confusion,” Bismarck, ND, Tribune, February 15, 1889, p. 4.; “Their Doubles: Public Men Who are Mistaken for Other Fellows,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, September 2, 1888, p. 10, special correspondence from new York.; “Has Every Man a Double?” Dallas Morning News, September 4, 1888, p. 2.↩

“Col. Ward in Louisville: He Gives His Views Concerning the Clayton Murder,” Arkansas Gazette, May 9, 1890. This article also a good example of Ward as conversationalist, telling the latest gossip about a famous murder case in Little Rock.↩

Cincinnati Enquirer, May 23, 1889, p. 8, available on Newspapers.com.↩

“Col. Zeb Ward,” Louisville Courier Journal, December 30, 1894.p.3, available on Newspapers.com.↩

Little Rock Arkansas Democrat, May 8, 1886, reprinting “Race course news” from Memphis Appeal.↩

“Written on Hotel Books,” New York Evening World, December 9, 1887, p. 2.↩

“A Splendid Prize,” Nashville Union and American, November 13, 1867.↩

Thanks to Katherine Mooney for tipping me off to this article in an April 2015 email, and to Cathy Schenck of the Keeneland Library for providing me with an image from the library’s files. This story, which Ward apparently told while holding court with other horse men at the St. James Hotel in New York, was eventually widely reprinted, without mention of Wood’s name, from the New York Sun: see “Paid for the Last Negro,” Waco, Texas, Morning News, October 25, 1888, p. 2; Indiana, Penn. Weekly Messenger, February 1, 1888; “The Last Slave Buyer,” Wilmington, Ohio, Journal, February 1, 1888; Wilmington, Del., Morning News, January 27, 1888; Indianapolis News, December 31, 1887, which called Ward’s claim a “doubtful honor”; New Orleans Times-Picayune, December 27, 1887, which adds the claim that Ward had wanted to free Wood; Chicago Tribune, December 23, 1887, which makes the same claim about his wanting to free Wood; “Colonel Zeb Ward,” Rochester, NY, Democrat and Chronicle, December 20, 1887, which also makes the claim about “a woman slave whom he wished to set free”; Cleveland Leader, December 19, 1887, p. 4; Worcester, Mass., Daily Spy, December 28, 1887, p. 2; “The Last Slave Paid For,” San Francisco Bulletin, January 9, 1888, p. 4.↩

Other versions of this story: “A Story of Col. Zeb Ward,” Little Rock Arkansas Gazette, October 3, 1888; Nashville Tennessean, September 5, 1888; Independence, Kansas, Daily Reporter, June 26, 1886, with slight variation; “Took Gen. Grant’s Place,” Washington Evening Star, October 29, 1888.↩

“Busy Life Ended,” Arkansas Gazette, December 29, 1894.↩

“A Stiff Game of Poker,” Rochester, NY, Democrat and Chronicle, June 28, 1889, available on Newspapers.com.↩

Little Rock Arkansas Gazette, July 15, 1884, p. 8↩

Memphis Public Ledger, July 17, 1877. This and the breakage of Ward’s levee was widely reprinted nationally as part of coverage of flood. One of these reports also identified Ward as “formerly a river clerk in the Cincinnati and New Orleans trade.” See “Shipping News,” Vicksburg Daily Commercial, July 26, 1877.↩

“Out-of-Town People,” St. Louis Republic, January 4, 1894, p. 5.↩

Arkansas, Pulaski Co., 1845-1878, Vol. 11, p. 288, R.G. Dun & Co. Credit Report Volumes, Baker Library, Harvard Business School.↩

Kentucky, Fayette County, 1848-1880, Vol. 11, p. 17, R.G. Dun & Co. Credit Report Volumes, Baker Library, Harvard Business School.↩

Kentucky, Franklin County, 1848-1880, Vol. 13, p. 111, R.G. Dun & Co. Credit Report Volumes, Baker Library, Harvard Business School; Kentucky, Woodford County, 1852-1878, vol. 41, p. 263. On Robb, see “Em. Sir D. P. Robb,” Frankfort Roundabout, May 14, 1904, p. 6, on Newspapers.com.↩

Tennessee, Davidson County, Vol. 5, p. 176, R.G. Dun & Co. Credit Report Volumes, Baker Library, Harvard Business School.↩