Revision bdd2ba2ca508e348a208d2fc1f7c6e185ee1ef28 - click here for latest revision

Zebulon Ward

The man whom Henrietta Wood sued for her kidnapping.

According to gilmore1930, Ward was born in Cynthiana, Kentucky, and moved to Nashville at the close of the Civil War, where he was a lessee of the Tennessee penitentiary until 1870. He then moved to Little Rock by 1872-1873, where he secured a ten-year lease of Arkansas’s penitentiary. “Colonel Ward made a fortune at each institution, and left an estate, consisting of Little Rock property and plantations, valued at six hundred thousand dollars. He was one of the most influential citizens of Arkansas. He … would pursue most any activity which would bring him financial returns.”1

Early Life

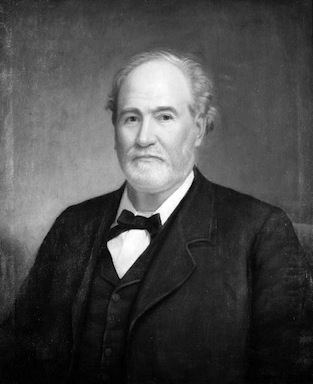

Sketch of Zebulon Ward from Louisville Courier-Journal, January 2, 1895, p. 7, available on Newspapers.com.

Ward was born in Cynthiana, Harrison County, on January 14, 1822, one of ten children born to Andrew Ward and Elizabeth Headington Ward.2 See his parents’ marriage certificate. The 1820 census for his parents shows them living in Harrison County. The 1830 census entry shows them in “Eastern District” of Harrison County, and has a male between the ages of 5 and 10 in the household. Ward’s brother, Andrew Harrison Ward, was a lawyer in Harrison County who went to Transylvania College sometime in the 1830s, eventually passing the Kentucky bar in 1844 and going on to a long legal and political career.3

On his mother’s side, Ward’s grandfather was Zebulon Headington, who arrived in Kentucky as early as 1785 and died in 1841. According to family history, he had served as a quartermaster in the Revolutionary War in Virginia.4

On his father’s side, Ward was descended from an Irish family that had settled in Virginia in the 1720s and then came to “Maysville by flatboat” (according to Ward’s brother) after the Revolutionary War. His father Andrew Ward settled in Harrison County in 1800 and knew the tanning trade; he and his young wife moved to Urbana, Ohio, at the invitation of his father’s cousin, Colonel William Ward, but returned to Harrison County prior to the War of 1812, in which Andrew Ward served.5

Family histories suggest Ward worked in the steamboat business as early as the late 1830s, when his brother Andrew Harrison Ward took a job as a purser on a Mississippi steamboat. A sister’s letter at the time said that “Brother Harry and Brother Zeb are both on The River now, and happy, of course.” His niece later reported that “Uncle Zeb remained ‘on the River’ much longer than Father did.”6

An obituary for Ward likewise reports that:

Upon attaining manhood young Ward became a clerk on a Mississippi River steamboat, engaging in that occupation several years. Subsequently he went to Nashville, Tenn., but his health declined there, and he journeyed to Cuba, where a sojourn of some time restored his wonted good health. Returning home about the time the Mexican War broke out, he became imbued with the war spirit and left for Mexico and joined the American army, serving in the field with distinguished credit to himself. After the war, he contracted the California gold fever and resolved to join the exodus to the Pacific slope in the palmy days of 1849. He went thither by way of Panama and reached California after an eventful journey.7

According to a family genealogist, “at 21 years of age he embarked in the steamboat business in Nashville, Tennessee, followed by some time spent in business in Cuba”; the same source claims, like the obituary, that he fought in Mexican War and then joined Gold Rushers to California.8 ] He then returned to Kentucky and got into the steamboat business again in Covington, Kentucky.9

I haven’t been able to confirm all those details, though Ward’s rambling fits with this evidence:

- Haven’t found a record for him in the 1850 census.

- He doesn’t appear in the Harrison County Tax Assessment Rolls in any year between 1841 and 1852, even though many of his brothers and mother remain there.

- A “Zebulon Ward” does appear in a list of recipients of letters published in the Sacramento Transcript throughout February and March 1851; see, for example, issue of March 4, 1851, found on GenealogyBank.com.

- A “Zebulon Ward” appears in a list of unclaimed letters in the New Orleans Daily Picayune, April 19, 1850, available on America’s Historical Newspapers.

- A “Z. Ward” appears on a passenger list for the steamship “Alabama” for “Chagres” (Panama?), published in New Orleans Daily Picayune, May 11, 1850, p. 1, available on Newspapers.com, and the Alabama did take forty-niners to California via Panama around this time; a “Z. Ward” then appears on a passenger list for the “steamer Northerner, for Panama” published in the San Francisco Alta California, October 31, 1850, p. 5, available on America’s Historical Newspapers.

- A “Z. Ward” checks into the Galt House in Louisville in December 1846, though he is listed as from “Jeffersonville,” and “Z. Ward” also has letters waiting for him in Louisville on July 1, 184810

The harder thing to confirm is his Mexican War service. Zebulon Ward does appear at some gatherings for Mexican War veterans in Arkansas late in his life, but some of these “informal” gatherings seem to have included Civil War veterans too.11 I have been unable to find any official record of his Mexican War service, other than in family genealogies and his obituary, which may at least indicate that Ward himself claimed to have served.12

Ward married Mary E. Worthen of Harrison County on January 9, 1851, as shown by a marriage certificate.13

A birth record for one of his children from Kenton County, Kentucky, suggests he may have been in Covington by February 13, 1852.

Sheriff in Covington

The Kenton County Court Order books prove that Ward was a sheriff in Covington at the time of Wood’s kidnapping. At the start of the January term, 1853, Phil F. Brown, the sheriff of the county, appeared before the court to move that Zeb Ward, R. B. Broaddus, R. R. Sumerwell, William J. McDonnold, and C. W. McDonnold be admitted his deputies. He swears the oath as a deputy sheriff again at the March Term. By January 1855, a new sheriff, William H. Wood, has been elected, and Ward no longer appears as a deputy.14 See also the reference to Ward as sheriff in Thomas Foraker Scrapbook.

Ward appears on the tax assessment rolls for Kenton County in (May) 1853 with one slave (valued at $400), one horse, no land, and gold (and other valuables) valued at $75. The timing of the tax survey makes it unlikely, but possible, that this slave was Henrietta Wood. The next year’s assessment, in 1854, shows Ward as owner of 6 acres in Kenton County, valued at $1,000, along with 1 slave valued at $500, one horse, and gold (and other valuables) assessed at $50. In 1855, he is assessed for three slaves (one over 16 years of age), valued at $1,000, but now with no land. By 1856, Ward is no longer listed in Kenton County tax rolls.15

George Blackburn Kinkead (1849-1940) wrote a brief memoir of his childhood that refers to Ward at this time, referring to his love, as a boy, of riding on the stagecoach line from Covington to Lexington:

On one occasion Zeb Ward, a powerful man, then Sheriff of Kenton county, and his batch of criminals destined for the penitentiary at Frankfort, riding on top excited my curiosity to such a degree, that I made it unbearable for the other passengers by my cries to be taken up with them. Being so often with my father, Mr. Ward knew me well, and to stop my cries as much as to gratify me, at the next stage caught me by the arm, and to the consternation of my mother drew me through the opening, and seated me by his side, and in the midst of this much desired society. How I bragged of this adventure to the negroes on the farm.16

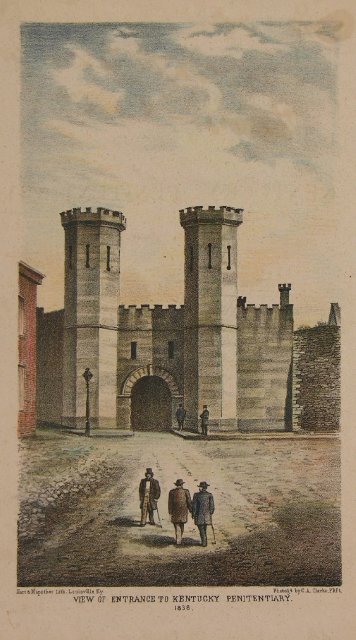

Lessee of Kentucky Penitentiary

He also was a lessee of the Kentucky penitentiary beginning in 1854 or 1855. He does not show up in the Franklin County Tax Assessment rolls until July 1856, when he is shown living in the town of Frankfort, owning four slaves (two over the age of 16), valued at $2000. In 1857, he is shown with seven slaves (three over the age of 16), valued at $3800. And in 1858, he owns eight slaves (five over the age of 16), valued at $4400. He does not appear in 1859 or later in Franklin County tax rolls, and does not appear to have ever owned land or town lots while keeping the penitentiary.17

He is mentioned in the famous Wines and Dwight report on prisons, which mentioned Ward’s arrangement while critiquing the general principle of the Auburn contractual labor system.18 Their account, drawing on a “history of the Kentucky Penitentiary, by William C. Sneed, M. D.,” explained:

The history of the Kentucky penitentiary affords additional proof of the same thing. In 1825, the principle was adopted of allowing the keeper, in lieu of all other compensation, one half of the profits, after defraying the current expenses. Joel Scott was the first keeper under this system, and he served for nine years. The clear profits from convict labor during his administration were $81,136. Mr. Scott was succeeded by Thomas S. Theobald, who took the prison on the same terms. The aggregate profits of his administration of ten years, the average number of prisoners being less than one hundred and fifty, were $200,000; and one year they reached the extraordinary sum of $30,000. Every dollar of the state’s share—$100,000—was paid into the public treasury. In 1855, Zebulon Ward leased the prison for four years, at an annual rent of $6,000; and at the end of his term, he retired with a fortune variously estimated at $50,000 to $75,000. Mr. Ward was succeeded by J. W. South, who leased the prison for a like period, though at the advanced rent of $12,000 a year. He also, at the end of his four years’ service, is reported to have retired with an ample fortune, as the product of convict earnings.19

Sneed’s history goes into much greater detail about Ward’s administration, reporting that he was nominated for keeper of the penitentiary by a Mr. Cunningham, and elected by a vote of the legislature on February 20, 1854.20 Ward began his term as keeper on March 1, 1855, prompting Sneed to resign his position as attending physician.21

Sneed says archly that “Mr. Ward, though a thorough business man, had no previous experience in the management of such an institution.” But he kept some of the former guards and assistants. Ward was, in Sneed’s telling, a political appointee who received support from friends in high places, even though rumors of “his ill treatment of the convicts, and of the wretched condition of the sleeping apartments in the cell buildings” began to circulate almost immediately and sparked a grand jury investigation ordered by the circuit judge, W. C. Goodloe, in May. The grand jury gave a good report, dated May 23, as to the sleeping arrangements and cleanliness of the penitentiary grounds, but expressed “disapprobation of the severity of punishment inflicted on the convicts, in more instances than one, amounting, if not to a violation of law, is at least violating to the feelings of humanity.”22

View of Entrance to the Kentucky Penitentiary, 1838, Lithograph by C. A. Clarke, 1860

In his first annual report, Ward complained that many improvements were need to make the prison “comfortable to the prisoners, and profitable to the State and keeper. The entire prison is behind the age. There are not workshops enough to give employment to the number of convicts now in confinement,” he complained.23

As of January 1856, there were 10 convicts in the penitentiary there for “assisting slaves to run away,” three for “stealing slaves,” and one for “emigrating to Kentucky, (free negro).”24 A complete Register of Prisoners as of 1848 and 1855 can be found at the Kentucky Department of Library and Archives, Reel 7009891, and it includes Calvin Fairbank, Thomas Brown, and a mulatto man named James Blackburn who was sentenced for enticing slaves to run away, and was identified by lash marks on his back. (See photocopies I took of these reels.)

The physicians working for Ward praised his “kindness and attentive generosity and humanity.”25

On March 1, 1856, Ward began a new three-year lease of the penitentiary (of a projected six years); he paid a rent of $6,000 per year, plus all expenses. “By the provisions of this act the institution went into the absolute control and management of the keeper,” Sneed wrote. “The checks and restraints usually thrown around that officer were all now removed, and he had liberty to do as he absolutely pleased. No monarch ever had more unlimited control of his subjects, and no one ever exercised his own will more completely than the keeper of the penitentiary did, from the time the institution passed into his hands under this law, until the end of his term.” Sneed charged that Ward, the Governer, and the inspectors were all partisans together, making the whole arrangement a case of corrupt political patronage.26

In his second report, Ward complained again about the lack of machinery in the institution, focusing little on the condition of the convicts.27

Ward continued to manage the penitentiary until his term expired on March 1, 1859, when a new penitentiary elected by Democrats who had taken the legislature took over. Sneed’s summative judgment is that Ward completely “lost sight” of any “moral influence exerted over the inmates,” seldom allowing a sermon to be heard except in obedience to the law. “The law requiring the convicts who were unlearned to be taught so many hours on the Sabbath was a dead letter; and, in fact, all the laws in relation to their moral condition were neglected, and only one great idea made prominent, and that was—work.”28

Ward’s administration began apparently at the same time Calvin Fairbank was imprisoned for helping fugitive slaves, though Fairbank apparently misdates his taking over of the penitentiary to 1854.

Fairbank describes Wood very negatively:

Ward was a tyrant. He was called the ‘Blood Sucker’ of the county. He cared nothing for human life. Money was his religion (p. 116).

When Ward addressed the prisoners in March 1854, he said:

“Men, I’m a man of few words, and prompt action. Do your duties, or I’ll make ye! Go to your work.” That fell like hot shot. That was what it was. … [Later he said] “Men, I understand that some of you are dissatisfied with my time of working, I shall let no man hold a watch over me. I’ll not allow you to break me up. I came here to make money; and I’m going to do it if I kill you all. If any of you claim the ten-hour time of working, just get right up, and go to your cells!‘We all sat still and smiled. But it was like Shakespear’s smile—’When I smile, I murder.’ (p. 117).

Fairbank goes on to describe Ward’s system in chapter 17 of his memoir, describing it as a “rigorous, murderous rule” (p. 118) and the lease system as “virtually a sale” of the prison by the state to Ward, “with very little difference between the condition of the prisoner and that of an actual slave” (p. 119). Detailed descriptions of Ward’s regime follow.

In a later interview conducted when he was 80, Fairbank remembered Ward this way:29

Zeb Ward became warden of the prison in 1854. He leased it at six thousand a year and made one hundred thousand out of the lease in four years. To do this he literally killed two hundred and fifty out of three hundred and seventy-five prisoners. Ward was one of the strangest men I ever knew, physically handsome, socially magnetic, but utterly devoid of heart or conscience. He was a gambler, libertine and murderer under cover of the law. When he took the keys of the prison he said: “Men, I’m a man of few words and prompt action. I came here to make money, and I’ll do it if I kill you all.”

“He was as good as his promise. During his wardenship and that of J. W. South, who succeeded him in 1858, I received on my bared body thirty-five thousand stripes, laid on with a strap of half-tanned leather a foot and a half long, often dipped in water to increase the pain. All the floggings I received under Ward were for failure to perform the tasks set for me to do, generally weaving hemp—two hundred and eighty yards a day being what I was expected to perform, an utter impossibility. I was whipped, bowed over a chair or some other object, often seventy lashes four times a day, every ten blows inflicting pain worse than death. Once I received one hundred and seven blows at one time, particles of flesh being thrown upon the wall several feet away.

Fairbank was not the only abolitionist who was in the prison while Ward was the keeper. Thomas Brown, who moved from Cincinnati to Kentucky in 1850, was arrested, tried in Union Count, and convicted in 1854 on local suspicions that he was helping slaves escape, while his wife was forced to flee to Indiana. Brown was transferred to the state penitentiary on May 8, 1855, where he donned prison garb and had his head shaved. He alleged sexual abuse of women in the prison by prison officials30 On p. 16 of his account:

When Mr. Brown had been in the prison a short time, he was ordered to carry some reels of hempen yarn from the Rope Walk, up stairs; he was required to carry four in each hand at a time. … One morning, in attempting to ascend the stairs, he let a reel fall. Complaint was made that “Old Brown had worn himself out stealing negroes, and would not work;” whereupon he was stripped, and flogged with the ‘cat’ till his blood ran upon the floor …

Brown was also ordered by Ward to help build the new buildings being constructed on the grounds, and to endure constant “jibes, not curses, not only from the officers, but the poor convicts themselves, because he was called an ‘Abolitionist,’” along with several others in the prison accused of aiding slaves to escape, including Fairbanks. According to the account of his years in prison, on p. 17:

On his arrival at the State Prison, the head keeper was extremely glad to get another ‘Abolitionist,’ as he called him, in his power, expressing with an oath, a wish to be permitted to hang all such.

At one time Mr. Brown was sent to a keeper’s house, of an errand, and, it must be remembered, that on the streets of Frankfort, the same as within the walls, he wore the prison garb.

“I am sorry,” said Mrs. Ward, with womanly humanity, “to see so old a man as you, in the State Prison.”

“I am there unjustly, madam,” he replied.

“But did not a jury of your countrymen find you guilty?” she inquired.

“No madam,” he replied, “they sold me. They valued my poor old head at five hundred pieces of silver, and my Divine Master, they sold for thirty pieces. They called him a blasphemer, and a wine bibber, and they have slandered me, also.”

Woodford County Farmer

After his penitentiary lease, Ward purchased a large farm in Woodford County and relocated there.

Ward doesn’t appear to show up in Woodford County until 1859, after purchasing some land there in December 1858.31 He made an especially big purchase of 144 acres of land from H. B. Bohannon in May 1860 for $12,269, paid in increments (and partly in mules).32 Various other entries in county deed books show him purchasing property in the county or in Versailles between 1861 and 1866.33

His first appearances in the Woodford County Circuit Court Order Book are in Book AA, which begins in 1860.34

In the Woodford County Court Order Books, he first appears in September 1859, where the tax assessor reports an assessment on his property taken prior to May 1 but just now being recorded. He is listed as the owner of 443 acres of land valued at $33,250 and 15 slaves valued at $13,000, as well as cattle, horses, and value, for a total value of $71,450.35 He does not appear in the indices for Books M and N of the county court order books, which cover the years 1860-1867.

Civil War Years

Tim Talbott found a letter from Zeb Ward to Henry Wise, showing that Ward sent a special hemp rope for Brown’s hanging, as well as another pamphlet suggesting Ward’s special hatred for abolitionists.

Jack Shuler’s history, The Noose, appears to suggest that the rope Ward sent was actually used to hang Brown.

At the beginning of the war, according to the 1860 Slave Schedule of the Census, Ward owned 27 people.

He apparently sold some goods to the Confederate Army.

State Legislator in Kentucky

Ward was in the legislature from 1861 to 1862 or 1863, as a state senator (or representative?) from Woodford County.36 In 1864 he was an alternate delegate from Kentucky’s “Union Democratic Delegation” to the National Democratic convention in Chicago.

A search for “Zeb. Ward” reveals many of his votes in the Kentucky House Journal for 1861 and 1862, available on HathiTrust.

He is described by whartonwilliams1986, p. 122, as a “Unionist and a member of the state legislature,” whose farm joined Edgewood, the farm of W. J. Jones and his wife Martha. The Joneses (who were Confederate sympathizers) rented their farm to Ward in September 1863, and Martha Jones later registered a complaint, in an April 5, 1864, entry, that Ward had not paid the rent he owed (p. 155).

During the war, both Ward and Jones appear to have hired enslaved men to each other to break hemp, a major agricultural product of the area. On January 25, 1862, for example, Martha Jones noted that “Men broke hemp today, 4 of Zeb Ward’s negroes here [hired]” and on August 10, 1860, “Willis hired men to Mr. Ward [a neighbor] today to cut hemp.”37

Slaves who Joined USCT

Tim Talbott has a post about enslaved men owned by Zeb Ward who joined the USCT. Their names were:

- Clay Ballard (see postwar Freedmen’s Bureau claims in 1865 and 1866)

- Weston Toles

- Tillman Toles

- William Simmons (note that a fourteen-year-old Arthur Simmons was living with Henrietta Wood in 1870—related?)38

- Mat Haggins

- Lewis Wilkinson (some Wilkinsons also live with Henrietta Wood in 1870)

- George Washington

Lessee of Tennessee Penitentiary

I searched the Tennessee Senate and House Journals in Sabin Americana, and found mention of a lease with Messrs. Ward and Briggs for the period of four years beginning in July 1866. During their tenure there was apparently a big fire at the prison that destroyed most of the workshops. A settlement was made with Ward and Briggs in July 1868. According to gilmore1930, this is the same Ward, and the House journal confirms it by noting that one of the convicts in the prison in 1868 was convicted of “impudence to Zeb. Ward” and “Sent to Quarry, with ball & chain.39 There was apparently upset in 1868 that Ward and Briggs were not paying the money due the state from the lease of convict prisoners.40

The lease appears to have finally ended in 1869 or 1870.41 There was subsequent controversy about bonds that were issued by the state to repay Ward.42

Lessee of Arkansas Penitentiary

Portrait of Zeb Ward, from Encyclopedia of Arkansas

Beginning in November 1873, Ward was a partner of John Peck, who began leasing the labor of convicts at the Arkansas penitentiary in May 1873. Peck then transferred his lease to Ward on February 5, 1875.

According to an entry by Carl Moneyhon in the Encyclopedia of Arkansas:

In 1873, as Reconstruction came to an end, the state legislature revised its program of prison leases and ended payments made to the lessee to support the prisoners. That year’s contract with John M. Peck and his silent partner, Colonel Zebulon Ward, leased prisoners to Peck and required that the lessee furnish labor, food, clothing, and housing for them. The state was to have no expenses. In 1875, Ward bought out Peck and held the prison contract until 1883. Ward profited greatly from his contract, benefitting from the rapid increase in the state’s prison population from 1876 to 1882 after the legislature’s passage in 1875 of a law that made the theft of any property worth two dollars or more punishable by one to five years of imprisonment. Ward also received the contract to build a major expansion of the state prison, using convict labor.

On the lease system in Arkansas generally, see zimmerman1949, Garland Bayliss, and Calvin Ledbetter.

See letters from Ward included in George Washington Cable’s, The Silent South.

See the 1875 report on Ward’s management of the penitentiary, which was sparked by articles published in the Evening Star by Daniel O’Sullivan.43

According to gilmore1930, 28, drawing on interviews conducted in 1930:

Col. Zeb Ward and Will Ward, a son, were characterized as mean men. Will Ward was spoken of as a drinker, and a whipper. Zeb Ward seemed to have had power to do anything in Arkansas. He was able to manage the courts, the railroads, and a large percent of the business men.

Ward apparently was a friend of the Arkansas governor and former Confederate Augustus H. Garland.44

Yet he was also apparently indicted for fraud against the city.

A “Zeb Ward” is listed as a “contractor” in a book of members of the Arkansas Board of Trade in 1901.

See testimony before the Senate about Ward’s management of the penitentiary.

Horse Racing

- There appears to have been a horse named after Ward in the 1888 Kentucky Derby; see chew1974, p. 276

- Ward’s taste for horse racing appears to have dated back to the 1850s and the 1860s, and it continued during the Civil War and into 1872

- He was connected with the racing horse trader Henry Price McGrath and a member of the Kentucky Association, and he took a horse to a race in Massachusetts in 1862

- One of his horses was Mollie Hambleton

- Morgan’s Confederate raiders reportedly stole a mare worth $4,000 from Ward in 1862; also referenced here; for a similar raid narrative, see Extact of a letter from R. A. Alexander.45

- Ward was briefly rumored to have died in 1864, as reported by a sporting magazine in New York who described him as “a very honorable and enterprising supporter of the turf”

- In a June 7, 1862, article in Wilkes’ Spirit of the Times vol. 6, no. 14, p. 217, Wilkes announces that Ward plans to bring numerous entries to an upcoming “New York Turf meeting,” some colts to sell as saddle horses, as well as the thoroughbred stallion Sailor, which he plans to put out to stud for owners of mares in the area who would like to try for a thoroughbred colts. A subsequent, June 21, 1862, article in the paper (vol. 6, no. 16, p. 249), announces the arrival of “the great racers of Kentucky,” including “Captain Moore and Hon. Zeb. Ward, with their magnificent strings of race horses.” Ward has brought “Sailor, by Yorkshire, who beat Bettie Ward in the great four-mile race for the Challenge Vase at Louisville, when Mollie Jackson won it; Reporter, a noted winner, by Lexington, out of an Eclipse mare; Pope Swigert; Blondin, by Lexington, out of a Glencoe mare, in the three-year-old stakes; and a filly by Lexington, in the stake, play or pay, at New York.”46

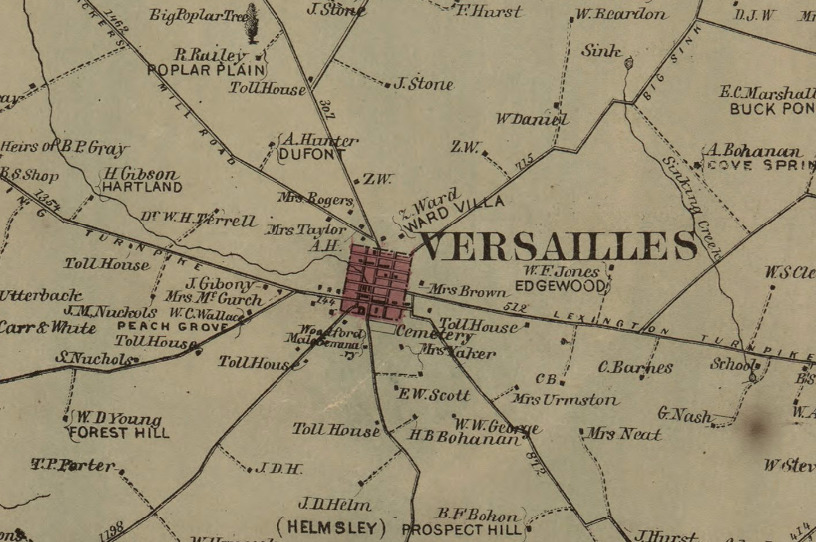

Map showing location of Ward’s horse farm in Versailles, clipped from topographical map by E. A. and G. W. Hewitt (1861)

According to whartonwilliams1986, 84, Ward appears in a detailed account of the Kentucky horse district in the March 29, 1862, issue of Spirit of the Times. The article is available in the AAS Periodical Series on EBSCOHost (where I got several other hits by searching for Ward that I need to investigate further). In the March 29 article, George Wilkes, the editor of the Spirit of the Times, wrote a letter back to his paper describing his visit to Cincinnati and then to Frankfort, where he hired a buggy to make “a journey of fourteen miles to the residence of Hon. Zeb Ward, at Versailles”:

I was for the first time in what I had known by story as the blue grass region, where everything in nature thrives, and where man himself culminates in physical perfection with the descendant of the barb. On all sides I beheld a beautiful rolling country, dotted with browsing stock, and already covered with a verdure not due to our more northern pastures for a month to come. This was the blue grass, whose closely matted roots harbor a warmth that responds instantly to the first touch of spring; and which indeed, retains at all times so large a vitality and such liberal excess that it will support stock during the entire winter. …

They say that the hospitality of the people of Kentucky ruins the business of the taverns. I found two proofs of the maxim, in the absence of a single roadside inn between Frankfort and Versailles, and in the determined refusal of Mr. Ward to permit my carpet-bag to go to the hotel of his town. A snug corner of his fine mansion, therefore, gave me quarters for the night, while an abundant supper and some two or three draughts of genial old Bourbon sent me tranquilly to bed.

The storm still prevailed in the morning, but time was so precious with me as to put weather at a discount; so Mr. Ward ordered up his top-buggy, and placing a little nigger behind in order that he might open gates and let down the bars, we started out for an interior drive among the racing farms of Woodford county. On our way across the fields of his own estate, a broad stretch of over six hundred acres, all in use, Mr. Ward directed my attention to a lot of yearling colts and fillies, which came to his whistle in a corner of the pasture. The two of these which he prized most highly were a bay filly by Lexington, dam by Glencoe, out of Eudora; and a bay filly by Scythian out of Cottage Girl, by Ainderby. The Lexington filly, however, was the object of his especial pride, and he confidently looks forward toward a career of distinction for her on the turf.

Wilkes also visited Ward’s stables, which appear to have been maintained by a Mr. Clinton, as well as the much larger neighboring estate of Robert Alexander.

From Katherine Mooney, in email dated April 28, 2015:

As far as how deeply he was into Thoroughbreds, it was pretty deep–his connection to Price McGrath is significant, since McGrath owned the first Kentucky Derby winner. Ward also owned a great horse named Tipperary, who was part of this sort of three-way duel for supremacy throughout 1864–and he took that horse everywhere to run him, including Saratoga and Monmouth Park in New Jersey. (The jockey was Abe Hawkins, who was a former slave.) In terms of how much money he made out of it, I’m not sure. It was possible for some people to make money off it, but usually not people who were doing it on any large scale. I never quite figured out how/if he was related to the Ward Brothers of Lexington–Junius Ward was the elder–who were shareholders in the Metairie Course at New Orleans in the 1850s, which was the biggest, glitziest racetrack in America. The other shareholders were bigtime Louisiana and Mississippi planters, so that meant major money. I’ve got a map indicating his farm was on Big Sink Road near Versailles, which was then and is now where the seriously fancy farms are. Obviously not every single one is a huge operation, but nobody around there was hurting. To give some context on values, Ward’s neighbor Robert Alexander paid $15,000 in 1855 for the racehorse Lexington, expecting to turn him into a breeding stallion. People at the time thought that was a good bit of money to pay for a horse (which, translated to today’s dollar values, it was, but, given what people pay for Thoroughbreds now, not much has changed.)

Unfortunately, I don’t think the match race was what brought him back to Kentucky–it actually took place in New Jersey, though Ward was a big fan of the Kentucky horse involved, John Harper’s Longfellow, and he was the major correspondent about the race in the Spirit of the Times (where he vindicated the performance of John Sample, Longfellow’s black jockey.) (That’s “The Saratoga Cup,” Spirit of the Times 14 Sept 1872, 65.)47 Harper was one of Ward’s neighbors, and at the time of the race, he’d just been involved in a lynching–the best account of that and of a lot of this period in that part of Kentucky is MaryJean Wall’s How Kentucky Became Southern, which I highly recommend.

Miscellaneous

A brief article in New York Sportsman, January 21, 1888, p. 63, refers to Wood v. Ward:

Colonel Zeb Ward of Little Rock, Ark., who left this city last week for home, thinks that he was the last man to pay for a negro slave in this country. A negro woman who had been in his possession for several years, while a suit regarding her ownership was pending, afterwards brought suit against him for services and gained a verdict. When Colonel Ward made out a check he worded it: “To pay for the last negro that will ever be paid for in this country.”48

- Humorist Opie Read remembered Ward being present when a deputation of “negroes” in Little Rock came to shake hands with Ulysses S. Grant, and that one of the deputation recognized Ward as the lessee of the penitentiary and “drew back”

- He was a stockholder in a hot springs company

- Mentioned by George Washington Cable in his critique of the convict leasing system

- Owned a controlling interest in one of the first municipal waterworks companies in Arkansas, as well as Mountain Valley Water Company

- A Zeb Ward building was built in Little Rock in 1881

- Ward was eventually a director of the Gazette Publishing Company in Little Rock, and was described there as “Zebulon Ward, capitalist”

- Ward’s Little Rock house is now occupied by a law firm that keeps a brief biography of him online; see also notice about the Ward-Heiskill house sale

- His tombstone, which puts his birth date as January 14, 1822, and his death date as December 28, 1894; same page contains an obituary that puts his estate at $600,000

- There may be an article about Ward in Woodford Sun newspaper, May 21, 1896, according to notes kept at the Woodford County Historical Society

- Some of Ward’s goods, specifically chairs and hemp bagging, are listed in a report of the Kentucky State Agricultural Society in 1858 and 1859, at which time he is listed alternately as a resident of Franklin County and Woodford County. He also purchased a harness horse for $700.

- One of the WPA interviews, with Mary Jones, recalled her mother as having worked for Ward: “After freedom, when the old folks died out, she cooked for Zeb Ward—you know him, head of the penitentiary”

- Look for a WPA narrative collected on August 22, 1936, by WPA interviewer J. C. W. Smith from John Wade, Little Rock man, which tells a “Zeb Ward” ghost story according to Alan Brown, Shadows and Cypress

- His son, Zeb Ward, Jr., participated in a welcoming parade for President Harrison.

- On Ward’s Kentucky background, see this genealogical chapter.

- Letter from Zebulon Ward to Kentucky Governor Thomas Bramlett, March 10, 1865, dated Lexington

- Did he own land in Ohio, perhaps given him by his father or great-uncle? See ward1961.

- Bill for the relief of Zeb Ward passed by U. S. Congress, to reimburse him for money he had contracted to receive for housing U.S. prisoners

R. G. Dunn and Company Credit Report Volumes

See spreadsheet for Ryan Shaver’s transcriptions. Highlights:

- From 1876: Reports on his $125,000 contract with Arkansas and his use of convict labor. “Got broke up in Ky. Is now building himself up again. paid all obligs. promptly, is a hard worker and stands good with this community.” Later notation in 1878 says he “Is earning money owns fine R.E. [real estate] pays promptly. highly regd. + safe for everything worth at least 150 m$ [$150,000] + in time will be worth nearly double that amt.49

- From Kentucky volumes: “good cr. [credit] was wealthy at onetime. est. his wor. [established his worth] If any transactions, have them well defined.”50

- From 1859: “Is a farmer on a lar. scale in Woodford Co. Has made a f. deal of money as keeper of the penitentiary.” Much longer discussion of his wealth and partnership with a man named “Robb” in the Woodford County volume, which describes his holdings in February 1862: “581 acres $32536, lots 2 m$, 24 slaves 96 c$, horses 44 c$.”51

- From 1867-1869: entries on his prison lease in Tennessee, including his litigation against state.52

Notes by Christina

A search for “Zeb Ward” returned three potentially viable result. The results of a search for “Zebulon Ward” was unsuccessful. Additional searches for alternative spellings and forms of his name will be forthcoming.

In the 1860 census, a 38-year-old Zeb Ward is listed as a farmer in Versailles, Kentucky. Ward is listed as having been born in Kentucky. The value of his real estate was $60,000 and the value of his personal estate was $30,000. Along with Ward’s family, one laborer named John Cole (38, born in Kentucky) is listed as part of the Ward household.

In the 1870 census, a 48-year-old Zeb Ward is listed as a [hemp?] manufacturer in Lexington, Kentucky. The value of his real estate was $50,000 and the value of his personal estate was $10,000.

In the 1880 census, a 57-year-old Zeb Ward is listed as a “contractor for penitentiary” in Little Rock, Arkansas. It states that his parents were both born in Maryland. Other members of his household include his wife Mary (56), two daughters (20, 19) and a son, Zeb Jr. (21).

Notes by Ashley

Notes on mancini1996. The index shows Zebulon Ward references on pages 119-20, 122, 123

- The convict lease as beginning “in earnest” in 1873: under the new terms, the state would not pay lessees for taking prisoners, but it also was not being paid by the lessee in compensation for the prisoners’ labor. It was private—not public—revenue that was gained from convict labor at this point. A more mutually beneficial (financially speaking) system was “still a decade away.” (119)

- Colonel Zebulon Ward was “a secret partner” of lessee John Peck (to whom the state’s prisoners had been leased for a ten year period from 1878 to 1883). Ward “bought Peck’s share in the lease” from 1875 to 1883. (119)

- Zebulon gained favor with state politicians by regularly “treating legislators to lavish dinners.” The Democratic-led legislature that came about with Redemption in 1875 saw the passing of criminal laws that would furnish the state with more prisoners: between 1876 and 1882 the prison population increased from 400 to 600. It wasn’t until the state contract with Ward ended in 1883 that Arkansas began a leasing system that (like other southern states) required lessees to pay the state for the first time (119-120)

- Before coming to Arkansas, Ward was a member of Kentucky’s legislator from 1861-63, and also the warden of Kentucky’s state penitentiary. He also leased prisoners in Tennessee at some point before coming to AR. In Arkansas, he had a reputation for being an “arrogant” and “hard-drinking flogger,” a description he apparently shared with his son Will to whom he delegated “many matters” in working the convicts. An 1880 outbreak of typhoid-pneumonia among a group of his convicts working on railroad construction led the state to “[decide] to seek other bids” for future lessees.

- Sources from mancini1996 include: Gilmore, “Convict Lease,” 24; for an example see Arkansas Gazette, 27 February 1979, 4; Genealogies of Kentucky Families (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co., 1981), II: 598; Ward quoted by Cable in Silent South, 123; Gilmore, “Convict Lease,” 28-29; Physician’s Report, 1880, 3-5; Committee on the Penitentiary, Arkansas House Journal, 1881, 423.

Excerpt from the Genealogies of Kentucky Families:

“Of the family of Joseph Ward of the Seth Ward line in Amelia County, Va., we have in Kentucky the families of William Ward of Lexington, Ky., died, 1804–the late Judge Quincy Ward of Bourbon County; Dr. John Ward, of Louisville, Ky., and Mr. Edwin Ward of Georgetown, Ky. Still another branch of the Wards is represented in the descendants of Andrew Ward, of Harrison County, Ky., the late Hon. A. Harry Ward, of Cynthiana and his brother, Col. Zebulon Ward, deceased who was at one time Warden of the Kentucky Penitentiary and member of the Kentucky Legislature from Woodward County, from 1861 to 63. Andrew Ward, their father and Col. William Ward, the founder of Urbana, Ohio, were closely related–he, the founder, was a son of Capt. James Ward, killed at Point Pleasant battle, Oct. 10, 1774.” (598)

Notes on Harry Williams Gilmore, “The Convict Lease System in Arkansas,” M.A. thesis, George Peabody College for Teachers, 1930.

- Part II (of V parts) of the thesis “presents the management of the penitentiary under the lessee, Colonel Zeb Ward, 1873-1883.” (Gilmore 1) It’s pages 13-29 of the thesis.

- Ward was Mr. Peck’s partner from November 13, 18733 (15), and Peck transferred the lease to him on February 15, 1875. (17)

Personal info on Ward:

- Born in Cynthiana, Kentucky in 1882 (which is obviously not true)

- Leased KY penitentiary for 4 years in 1855

- Moved to Nashville, TN at the end of the Civil War; became a lessee of the TN penitentiary until lease expired in 1870

- Active citizen of Little Rock, AK from winter of 1872 to the time he became Peck’s partner on the lease; would become “one of the most influential citizens of Arkansas,” taking part “in all civic activities and [pursuing] most any activity which would bring him financial returns.”

- Left an estate “of property and plantations, valued at six hundred thousand dollars” (Gilmore 17-18)

Ward and the Penitentiary

- Had charges of mistreatment and neglect of the penitentiary’s prisoners brought against him after an official investigation of the penitentiary between Nov 13, 1874 and Sept 1875 (Daniel O’Sullivan, editor of the Evening Star, published the results in a September 2, 1875 issue of the newspaper) (Gilmore 18-22) [It’s possible that the Evening Star and the Gazette are the same paper … because the whole time his footnotes are citing the Gazette … although, the Gazette appears to have also been a Lexington, Kentucky newspaper (but there is also an Arkansas version)]

- According to an issue of the Evening Star, Ward’s “theory in the management of a prison is that he cannot be too hard on thieves, murderers, and such scoundrels unless he cripples and kills them, and so far as hard work is concerned he gives them all they can bear.” (Gilmore 24)

- Ward had enough of a negative reputation that prisoners would supposedly try to get longer sentences to avoid being sent to the AR penitentiary: “The life of a convict was so hard under the Ward regime that federal prisoners who had been given short sentences by the district judge would ask for longer sentences in order that they might serve their terms in a Federal prison rather than in the Arkansas penitentiary.” (Gilmore 28)

- Both he and his son Will characterized as “mean men.” Ward, nevertheless, had great power and influence in AR. (This from personal interviews)

- Relevant Primary Sources from Gilmore include Gazette, Oct. 14, 1875; Reports of the Board of Commissioners for the Management of the Penitentiary (Little Rock, 1876) 1-3. (This is possibly the Report, not able to find an 1876 version though; anyway, I made a pdf of pages 1-3 of the 1875 version (which seem directly relevant).) The Daily Herald. Jan 27, 1876; Laws of Arkansas, 1883, 171-2. Gazette Dec. 29, 1894; Oct. 25, 1890 (quoting Louisville Evening Post, Oct. 22, 1890); Apr 17, 1880; Oct. 13, 1875; Oct 14, 1875; Sept 3, 1875; Democrat, Apr. 16, 1880; Southern Standard, Jan 4, 1895(or 1885?); The Evening Star, Jan 17, 1876; Jan. 21, 1876; Feb 19, 1876; Tennessee, Senate Journal of the First Extra Session of the Thirty Seventh General Assembly, 1872, 80-81

To-Do List

- qq Look in Cumberland steaming book

- qq Go through Covington Journal for months before kidnapping

- qq Go through probate records on Ancestry

gilmore1930, 18. Gilmore often references an article, potentially an obituary, about Ward from Louisville Evening Post, October 22, 1890. May have this at the Filson. Similar points about Ward’s business acumen made in ward1961 and “Col. Zeb Ward,” Louisville Courier-Journal, December 30, 1894, p.3, available on Newspapers.com.↩

See ward1961, 60; lafferty1945, 9, which says the birthdate was recorded in the “Ward Family Bible”; gilmore1930.↩

See lafferty1945; ward1961, p. 62.↩

See lafferty1945. The marriage record for Andrew and Elizabeth Ward shows her father’s name. Zebulon Headington’s will is in Harrison County Will Book D, p. 465-468, KDLA, and shows the inventory of his estate in October 1841, which includes three named slaves (Augustus, Cynthia, and Kate—possibly a family) valued at a total of $1350. I could not locate Andrew Ward in the will book, despite searching in Will Books C through F.↩

See lafferty1945 for more details.↩

lafferty1945, 75-75.↩

“Busy Life Ended: Col. Zeb Ward Passes Away at His Home in This City,” Arkansas Gazette, December 29, 1894.↩

See ward1960, family history by Helen Ward Lafferty Nisbet, held at the Kentucky Historical Society in Frankfort, link.↩

“Arrivals at the Principal Hotels,” Louisville Daily Courier, December 31, 1846; “List of Letters,” “List of Letters,” July 3, 1848, available on Newspapers.com.↩

See “War Veterans: Heroes of the Mexican War Meet and Celebrate,” Little Rock Arkansas Democrat, February 24, 1880, available on Newspapers.com; “Meeting of Mexican War Veterans,” Little Rock Daily Arkansas Gazette, June 20, 1878, available on Newspapers.com.↩

Based on footnotes in Damon Eubank, The Response to Kentucky to the Mexican War, 1846-1848 (Lewiston: Edwin Mellen Press, 2004), I tried James A. Ramage article in Register of the Kentucky Historical Scoiety 81 (1983) [9/22: no mention of Ward in the article, though it does mention a speech by “prominent attorney” George B. Kinkead welcoming returning veterans]; Salisbury article in Filson Club Historical Quarterly 61 (1987); Sam Hill, Report of the Adjutant General of the State of Kentucky, Mexican War Veterans (Frankfort, 1889) [found no reference to Ward in this book, which I examined at Kentucky Historical Society]; and Works Progress Administration, Military History of Kentucky [which indicates on p. 136 that a company of infantry formed in Harrison County was organized but not accepted into service because the requisite regiments had already formed]. But since Ward doesn’t show up in Fold3 for the Mexican War, it’s likely this is a legend.↩

See also this related marriage record.↩

Kenton County Court Order Books, 1853-1854, Kentucky Department of Library and Archives, Reel 551072. I couldn’t find anything about Ward in the previous order books on the previous reel, though I was relying largely on indices at the beginning of the book and quick skims of pages around the start of terms.↩

See Kenton County Tax Assessment Rolls, Microfilm 008091, Kentucky Department of Libraries and Archives.↩

See Kinkead’s memoir, dated August 21, 1921, in June Lee Mefford Kinkead, Our Kentucky Pioneer Ancestry: A History of the Kinkead and McDowell Families of Kentucky (Baltimore: Gateway Press, Inc., 1992), 252-253.↩

See Franklin County Tax Assessment Rolls, Microfilm 007980, Kentucky Department of Library and Archives.↩

For more on Wines and Dwight, see mclennan2008. The state prison is pictured in a birds-eye map of Frankfort from 1871, held at Library of Congress.↩

E. C. Wines and Theodore W. Dwight, Report on the prisons and reformatories of the United States and Canada, made to the Legislature of New York, January, 1867 (Albany: Van Benthuysen & sons, 1867), 260.↩

William C. Sneed, A report on the history and mode of management of the Kentucky Penitentiary from its origin, in 1798, to March 1, 1860 (Frankfort, Ky.: State of Kentucky, 1860), 514-516. Ward displaced the incumbent keeper, Newton Craig, by a final vote of 75 to 60.↩

Norman B. Wood, The white side of a black subject : enlarged and brought down to date: a vindication of the Afro-American race, from the landing of slaves at St. Augustine, Florida, in 1565, to the present time (Chicago: American Publishing House, 1897), 216.↩

See Brown’s three years in the Kentucky prisons : from May 30, 1854, to May 18, 1857 (Indianapolis: Indianapolis Journal Company, 1858), link.↩

See deed of property from John M. Coleman to Zeb Ward, Woodford County Deed Book W, p. 394. Also see the April 1859 sale of the store in Versailles operated by Ward and Robb, in Deed of Property by H. H. Culbertson to Zeb Ward, Woodford County Deed Book W, p. 488.↩

Deed of Property from H. H. Bohannon to Zeb Ward, Woodford County Deed Book X, p. 197.↩

One of these deed transfers was witnessed by Charles Mynn Thruston. See Deed from John B. Kinkead to Zeb Ward, Woodford County Deed Book X, pp. 367-368. Other entries in Book Y include pp. 85, 89, 127, 188, 216, 231, 239, 390 (the “Shelton House” in Versailles outside the courthouse, bought at auction), and 577. One of these shows that he was briefly a trustee at Woodford Female College.↩

See Woodford County Circuit Court Case File Index, Microfilm 7036112, KDLA. He appears in the index to this book, and also in BB, CC, DD, though I didn’t look at the specific pages discussing the suits, as the order books are unlikely to yield very much information about what happened in the cases. The general index also says he appears in Book Z on p. 187, but I could not find that reference.↩

Woodford County Court Order Book L, p. 258. Ward later contested some of these valuations: see p. 318. The assessment says that among his 15 slaves, 10 were over 16.↩

W. E. Railey, “Woodford County,” Register of the Kentucky Historical Society 18, no. 53 (1920), 64; “The Ward Family,” Register of the Kentucky Historical Society 6 (1908), 38.↩

Quotes from whartonwilliams1986, pp. 32 (1860 entry), 80 (1862 entry).↩

Also an Arthur Simmons from Louisville in the USCT, and later in school for the blind. There are multiple records for William Simmons in the 116 USCI on Fold3, and they imply that he remained enlisted until January 1867 when mustered out in New Orleans.↩

See pp. 75-79, 102, of Tennessee. General Assembly. House of Representatives. House journal of the … session of the … General Assembly of the state of Tennessee. A.D. 1868. Nashville [Tenn.], 1868. 279pp. Sabin Americana. Gale, Cengage Learning. Fondren Library, Rice University. 22 April 2015 http://galenet.galegroup.com/servlet/Sabin?af=RN&ae=CY3809487245&srchtp=a&ste=14.↩

See p. 93, 330, of Tennessee. General Assembly. House of Representatives. House journal of the … session of the … General Assembly of the state of Tennessee. A.D. 1868-69. Nashville [Tenn.], 1868. 520pp. Sabin Americana. Gale, Cengage Learning. Fondren Library, Rice University. 22 April 2015 http://galenet.galegroup.com/servlet/Sabin?af=RN&ae=CY3809487538&srchtp=a&ste=14. Also see Tennessee. General Assembly. Senate. Senate journal of the … session of the … General Assembly of the state of Tennessee. July, 1868. Nashville [Tenn.], 1868. 223pp. Sabin Americana. Gale, Cengage Learning. Fondren Library, Rice University. 22 April 2015 http://galenet.galegroup.com/servlet/Sabin?af=RN&ae=CY3809979412&srchtp=a&ste=14.↩

Tennessee. General Assembly. Senate. Senate journal of the … session of the … General Assembly of the state of Tennessee. November, 1868. Nashville [Tenn.], 1868. 363pp. Sabin Americana. Gale, Cengage Learning. Fondren Library, Rice University. 22 April 2015 http://galenet.galegroup.com/servlet/Sabin?af=RN&ae=CY3809979174&srchtp=a&ste=14.↩

See Ward’s testimony on the matter in Tennessee. General Assembly. House of Representatives. House journal of the … session of the … General Assembly of the state of Tennessee. A.D. 1869. Nashville [Tenn.], 1869. 1512pp. Sabin Americana. Gale, Cengage Learning. Fondren Library, Rice University. 22 April 2015 http://galenet.galegroup.com/servlet/Sabin?af=RN&ae=CY3809819338&srchtp=a&ste=14.↩

Report of the Board of Commissioners for the Leasing Management and Regulation of the Arkansas State Penitentiary, on the result of an investigation concerning the treatment of prisoners, and general conduct of the institution. Together with the testimony taken in the course of the investigation. September, 1875 (Little Rock, AK: 1875). May be the same as this book.↩

Josiah Hazen Shinn, Pioneers and Makers of Arkansas (1908; Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Company, 1967), 324.↩

Coverage also in “Morgan at Versailles,” Philadelphia Inquirer, July 24, 1862.↩

Image of articles sent to me by Cathy Schenck.↩

Thanks to Katherine Mooney for tipping me off to this article in an April 2015 email, and to Cathy Schenck of the Keeneland Library for providing me with an image from the library’s files.↩

Arkansas, Pulaski Co., 1845-1878, Vol. 11, p. 288, R.G. Dun & Co. Credit Report Volumes, Baker Library, Harvard Business School.↩

Kentucky, Fayette County, 1848-1880, Vol. 11, p. 17, R.G. Dun & Co. Credit Report Volumes, Baker Library, Harvard Business School.↩

Kentucky, Franklin County, 1848-1880, Vol. 13, p. 111, R.G. Dun & Co. Credit Report Volumes, Baker Library, Harvard Business School; Kentucky, Woodford County, 1852-1878, vol. 41, p. 263.↩

Tennessee, Davidson County, Vol. 5, p. 176, R.G. Dun & Co. Credit Report Volumes, Baker Library, Harvard Business School.↩