20131203 - Gilder Lehrman Center Talk Notes

This coming Wednesday, I’ll be giving a talk at the Gilder Lehrman Center at Yale as part of my fellowship here. So I’m using this page to collect my thoughts for the brown-bag presentation, which will be informal instead of a paper read verbatim.

Note: This is not an exact transcription of my remarks.

The goal of the talk will be to three things:

- Give people an impression of the phenomenon of refugeeing slaves to Texas.

- Talk about how I’m thinking about this phenomenon in relation to existing historiography about slavery and the Civil War.

- Give some brief hints about things that I’m finding in the sources.

Pre-Talk Notes

Introducing the Topic: Refugeed Slaves

The posted flyer for my talk features this image, so I’ll probably open with it:

Photo of a refugee family leaving a war area with belongings loaded on a cart, National Archives and Records Administration Civil War Photos, 200-CC-306

When I was asked for an image for my talk about Confederate refugees to Texas, this is the one I submitted, even though I really don’t know much about it. It’s not clear from the NARA’s description whether the refugees are Unionists or Confederates, or whether they are headed to Texas. But it will have to do as an image because few (if any) photographs of Confederate refugees west of the Mississippi survive today.

What we do have are numerous, vivid descriptions of Confederate refugees, many of which conjure up, in my mind at least, images like this one.

Consider, for example, the account of Kate Stone, one of numerous white refugees from northeastern Louisiana who fled her plantation on the Mississippi River a few months before the fall of Vicksburg. Arriving at a railroad depot in Delhi, Louisiana, this is what Stone saw:

The scene there beggars description: such crowds of Negroes of all ages and sizes, wagons, mules, horses, dogs, baggage, and furniture of every description, very little of it packed. It was just thrown in promiscuous heaps—pianos, tables, chairs, rosewood sofas, wardrobes, parlor sets, with pots, kettles, stoves, beds and bedding, bowls and pitchers, and everything of the kind just thrown pell-mell here and there. … While thronging everywhere were refugees—men, women, and children—everybody and everything trying to get on the cars, all fleeing from the Yankees or worse still, the Negroes.1

Stone’s picture captures well the “promiscuous heaps” of goods loaded into the wagon in this photograph. But one of the most conspicuous features of Stone’s account is also conspicuously absent in the photo: in Delhi, Stone saw, in addition to the refugees and piles of furniture, “such crowds of Negroes of all ages and sizes.”

“Negroes” appear twice in Stone’s description of Delhi, and in very different roles: on the one hand, slaves who had been liberated and sometimes armed by Union troops were what white refugees were running from. But on the other hand, Stone’s description indicates that in 1863 many white refugees—including Stone herself—were running west with large numbers—“crowds”—of enslaved people.

Other contemporary accounts confirm that large numbers of Refugeed Slaves, as they were known, were brought west by Confederate Refugees to Texas, especially after 1862.

- In November 1862, a Texas cavalryman in Arkansas declared that “every day we meet reffugees [sic] with hundreds of Negroes, on their way to Texas.”

- The British traveler Arthur J. Fremantle, who arrived in Monroe around the same time Kate Stone did, witnessed “hundreds” of slaves being “‘run’ into Texas,” so many that “the road … was alive with negroes.” One planter had “as many as sixty slaves with him of all ages and sizes” (80).

- And a Texas newspaper joined the chorus in October 1863 reporting that “refugees from Louisiana and Arkansas, with immense numbers of negroes, continue to pour into Texas, and the roads are all lined with them.”

- Long after the war, too, many formerly enslaved people remembered the roads being full of refugees bringing slaves from other states. Elvira Boles, who was interviewed for the Texas WPA Narratives, remembered being brought form Mississippi to Cherokee County, Texas, “in a wagon” by white agents of her master who said “we’d never be free iffen dey could git to Texas wid us.”

This is all anecdotal evidence, to be sure, but it indicates that if we had been able to set up a camera along the roads between Monroe and Marshall, or along the railroad tracks leading into Houston, the photographs we would have captured would have looked less like this one, and more, perhaps, like this one, which depicts slaves being moved southward by Confederate troops in Virginia.2

Historiography

Somehow I need to transition here to the point that these images fit uneasily with our conventional narratives about the Civil War, which most scholars now see as instrumental in undermining the power of Confederate slaveholders and ultimately ensuring the “destruction of slavery.”

Recent historians especially depict Louisiana—from which so many refugee planters fled—as an epicenter of a wartime process of emancipation after the fall of New Orleans to Union forces in the spring of 1862; as Union control spread into Louisiana’s rich sugar and cotton districts, according to this story, slavery quickly crumbled in the face of slave resistance, military campaigns, black enlistment in the Union army, and a mass exodus from plantations by enslavers and the enslaved alike.3

In other words, after a generation of landmark scholarship on wartime emancipation, images like this are far more familiar than the one with which I began:

Images like that, which show a group of refugee African Americans fording the Rappahanock River as Union soldiers look on, vividly convey what we have learned in a thousand ways: that the dislocations and abrasions of war provided unprecedented opportunities for African Americans seeking their freedom. The war, on this powerful account, sparked a massive slave rebellion that thoroughly destroyed slavery and enabled the “genesis” of something new—a free labor system—to begin rapidly during the war itself.

This overarching story has been challenged recently. There is an emerging literature, in works like downs2012, that calls into question just how liberating the war was for African Americans who wrenched their freedom from its gears. These works show that even after gaining their freedom, former slaves struggled with poor conditions in contraband camps and poor treatment at the hands of Union soldiers.4 Yet even these accounts may end up reinforcing the dominant historiographical storyline: the Civil War freed slaves, they agree, but freedom was not enough or what freedpeople expected. Those points are valuable ones, but they, too, don’t give us a good frame for understanding the refugeed slaves who were not even freed by the war in the first place, but were instead moved far enough away from Union lines to foreclose, for them, the opportunities that the war afforded to so many others.

We’re talking about more than a handful of cases here. It’s difficult to know exactly how many slaves were refugeed to Confederate Texas, but estimates range from 51,000 (a low, very conservative estimate proposed by baum2008) to 125,000; 150,000; or even more (the numbers preferred in contemporary sources). One newspaper editor in Marshall, Texas, claimed in October 1864 that “there are more negroes in the State now than were ever here before,” and added a year after the war that “there are, perhaps, to-day, double the number of negroes that were in the State in 1861” because of those who “came with the refugees that flocked into Texas from Missouri, Arkansas, and Louisiana.”5

We don’t have to take all of these estimates at face value to see that for a very large number of enslaved people, the abrasions of war did not bring freedom. Perhaps we should even think of these forced migrations as a continuation of a long antebellum history of what oakes1982 describes as slaveholders’ “pilgrimages” to Texas, which by 1860 had swelled the state’s slave population to almost 200,000. To put these numbers in perspective, the highest contemporary estimates of 150,000 would mean that as many slaves were refugeed to Texas as were recruited into the Union army from slave states (around 180,000). That would make the black refugeeing experience almost as common as the much better understood “black military experience.”

Historians have not, to be sure, been blind to the large numbers of refugeed slaves taken to Texas, but in general they have subsumed their story into the story of wartime emancipation and black military mobilization by the Union army. While noting the efforts of refugee planters who “redoubled their efforts to keep black people in thrall” by fleeing to Texas, historians generally emphasize the ways that refugeeing created new opportunities and motivations for escape by enslaved people, thereby adding “momentum to slavery’s decline.” By throwing slaveholders into motion, argues one recent account, the war further eroded the already dissolving control of slaveholders over bondspeople, so that “slave society, in effect, collapsed on the road.”6

Usually, in these accounts, one of the strongest evidences of slavery’s continued resilience during the war—the removal of tens of thousands of people to Texas—has been reframed as further evidence of its dissolution.

Now, my point is not to somehow write up a balance sheet of slaves freed or refugeed and use that to determine whether slavery survived the Civil War or was destroyed by it. To some extent both conclusions are true, often in the case of the same slave community.

Two examples:

Kate Stone, the Louisiana slaveholder with whom we began. In the spring of 1863, Stone’s journal contains countless observations about how many enslaved people were running away to Union camps. She also described increasingly bold resistance from some of the family’s household slaves, including one who confronted Stone’s mother with a carving knife before fleeing to the river with her two children.7 But by the time she wrote these lines, her family had already moved “the best and strongest of the Negroes” to a western salt works weeks before Union troops arrived in force in her parish. When she eventually fled with her mother for Monroe at the end of March, only about 30 slaves remained behind on their plantation. But even these were captured and taken to Texas with the others when Stone’s brother and a force of Confederate soldiers returned to her home, surrounded the “Negroes’” cabins, and carried off all but one who had joined the army and four who were considered too old to travel. In the end the Stones took nearly all of their 80 bondspeople to the Lone Star State, profiting from the hiring out of their labor until the end of the war.

Mary Williams Pugh another example. Her experience of flight from the Lafourche District of Louisiana with her father, John Williams, is often cited by historians as a further example of the breakdown of slaveholders’ power:

The first night we camped Sylvester left—the next night at Bayou B. about 25 of Pa’s best hands left & the next day at Berwick Bay nearly all of the women & children started—but this Pa found out in time to catch them all except one man & one woman. Altogether he lost about sixty of his best men.8

These losses surely were significant, but in the end Williams made it to Texas with 44 enslaved people, while his son-in-law, Mary’s husband, made it to Cherokee County with 69 or 70.9 Williams and Pugh then used this still considerable force to produce salt, a valuable commodity in wartime Texas—their success in refugeeing, however limited by their losses along the way, enabled them to return to their plantations in Louisiana after the war without having been completely destitute in the interim.

We miss the full story in cases like these if we focus only on the evidence that the war opened opportunities for freedom, and miss the ways that slavery survived. The narrative power of our stories about wartime emancipation have obscured from view a large number of enslaved people—like the nearly 200 I have just told you about—who need to be considered as more than just exceptions to a general rule.

Yet because of the dominant storyline about wartime emancipation, we still have only fragmentary knowledge of the ways strategies that slaveholders used to “refugee” slaves, what enslaved people did in Texas once they got there, and the complex choices that slaveholders and slaves alike made about what to do as Union armies approached.10

Those are the things I’m trying to uncover in this project.

Methods and Findings

Now I need to transition somehow to what I’m finding so far and talk a little bit about how I’m finding it. Identifying planters who refugeed slaves into the state has often proved as difficult as identifying the anonymous people in the photo above, partly because Confederate refugees to Texas were not always interested in being easily found. Nonetheless, they left behind telling traces in sources like:

- wartime county tax records, which showed that Louisana planter Harriet Weeks was able to take 50 slaves from the lower Teche region of Louisiana to Freestone County, while her traveling companion Mrs. M. P. Brashear, had brought 68 of her slaves.

- planters’ family correspondence, in which planters like Harriet Weeks’s brother William F. Weeks wrote back to family members about their success in bringing slaves to Texas. Weeks, for example, assured his father-in-law in October 1863 from Houston that “Negro property will be safe here when not one is left a slave in Louisiana.”

- runaway slave advertisements like this one, which sometimes indicated that a runaway had recently been brought to Texas.

- correspondence with governors of Texas and Louisiana; Official Records of the War of Rebellion; postwar records of the Freedmen’s Bureau, etc.

I will probably close by talking about the evidence I’m finding that some refugee slaveholders managed to do relatively well in Texas by hiring out slaves at Salt Works, railroads, or iron foundries, or by contracting with the Confederate military or state government to haul supplies.

Planters themselves usually complained about their poor luck in Texas and their impoverishment, and to be sure, they no longer had the standard of living to which they were accustomed. But we also need to weigh their complaints against their expectations about what they, as white elites, were entitled to. If we look objectively at their experiences instead of their descriptions of that lived experience, we can begin to get a picture of how refugee slaveholders continued to use enslaved labor for their own profit and survival.

Example: William F. Weeks.

Before the war, Weeks was one of the most heavily capitalized and technologically advanced sugar planters in Louisiana.11 During the war, he fled to Texas with large numbers of enslaved men, leaving his wife and young daughter behind. Once there, Weeks engaged in a number of business ventures simultaneously: he rented farms and put some slaves to work growing corn and cotton, using letters of introduction from the prominent Houston banker and merchant Robert Mills, to whom he also sold cotton for specie; he hired out slaves to cut lumber and make ties for a railroad company that was expanding during the war thanks to the transportation of troops; he hired out an enslaved man who was a cooper to make barrels; he used his teams and wagons to haul cotton and supplies; and so on. Ultimately Weeeks did well enough to rent farms not only for himself, but also for his sister, his brother, and their families, who all eventually moved to around the Houston area.

Now, if you had asked Weeks whether he was satisfied with these enterprises, he undoubtedly would have said “No.” To an antebellum sugar planter, these were small beans. Responding to a letter from his wife that apparently congratulated him on finding a favorable situation in Texas, the refugee sugar baron William F. Weeks scoffed, “I cannot think what you mean by my good luck. I have had none, have made nothing here but a little confederate money, and not enough of that to buy me a suit of clothes.”12

But on the very same day Weeks wrote to his wife about his misfortunes in Texas, he put on a different guise in a letter to his stepfather. Having secured a contract to hire his slaves to a railroad company that provided him with provisions and owed him between $15,000 and $20,000 in “new issue” Confederate notes, Weeks wrote that “I am doing very well so far.”13

Admissions like these are important, first of all, because they show that refugee slaveholders were still moving with an eye towards turning profits on the backs of thei bondspeople—just as they had in the decades leading up to the Civil War. And it also suggests that some of them managed, under the circumstances, to fare relatively well in their new environment.

It’s important to note that because refugees so often presented themselves as poor, wandering exiles who were ruined by the war—an image that has persisted in the popular memory of them:

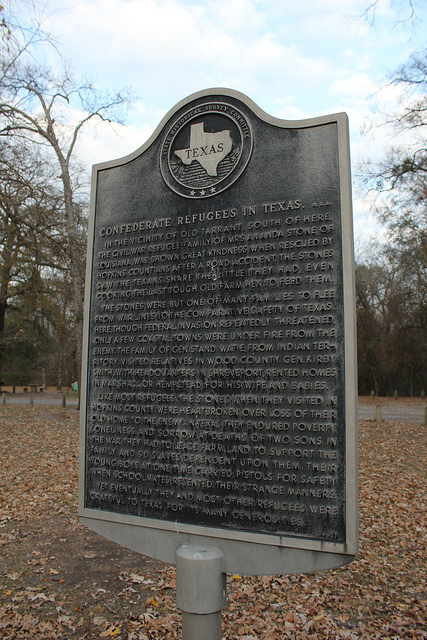

State historic marker about Confederate Refugees in Texas, which describes the Stones as “heartbroken over loss of their old home to the enemy. In Texas, they endured poverty, loneliness, and sorrow at deaths of two sons in the war. They had to lease farmland to support the family and 90 slaves dependent upon them.”

That depiction of refugees began during the war itself, when observers often commented on the impoverished state of white Confederate women in particular, obscuring the ways that these women continued to benefit from the labor of slaves. See, for example, this sketch in the Illustrated London News.

The “destruction of slavery” historiography about the Civil War may have inadvertently allowed images like this to stand by conveying the idea that planters really did lose everything. But in candid moments, even the most seemingly distressed refugee slaveholders admitted that they were not so bereft.

Kate Stone, for example, worried constantly about her family’s slaves running away from the salt works where they had been placed in Winn Parish, Louisia. “Then, what will become of us?” she asked in April 1863. Then, “we will be absolutely destitute.”14 Until then, however, Stone was not absolutely destitute, and insofar as she and other slaveholders like Weeks managed to get to Texas with forces of enslaved people, they continued to be something far less than wealthy but something far more than penniless. As Stone mentioned when she got to Texas, comparing her situation to those refugees who had lost all of their slaves, “We seem to have almost nothing but servants, and yet we are comfortable, comparatively so.”15

Post-Talk Debriefing

I got a lot of great questions after the talk that should help me as I move forward.

Many people encouraged me to think differently about the framing of my evidence. For the purposes of the talk, I had presented refugeed slaves as evidence of slavery’s survival that should lead us to qualify historiographical claims about the war’s total destruction of slavery. But Dael Norwood suggested that another way to look at this is to ask the question: “What constitutes a working system of slavery? How does slave refugeeing shed light on that question?”

I like that way of framing the question, because in truth, I’m not really wanting to challenge oakes2013 or the storyline that the war destroyed slavery as an institution. I don’t even want to suggest that it was easy for slaveholders to survive on the road, since I basically agree with sternhell2012 that movement disrupted the normal operations of the system and seriously weakened it. I do think the focus on slaves who were freed directly by the war directs our attention away from the stories of those who were refugeed, and that we need to reckon with those stories. But I really don’t think the refugeeing evidence as a whole adds up to a reason to doubt the “wartime destruction of slavery” narrative.

Dael went on to suggest that one way forward could be to move away from a false dilemma about whether slavery, as a system, was destroyed or survived, and instead see the refugeeing experience as an example of familiar patterns of transformation in slavery (westward movement, industrialization, capital investment, hiring out, etc.) accelerated to an unnatural rate by the exigencies of war. It’s the steamboat-capitalism engine vision of slavery presented by johnson2013 sped up to an unsustainable speed—still going, but with pieces falling off in every direction.

I spent a lot of time at the end of the talk discussing the question of whether refugeeing paid—to what extent did people like William F. Weeks come out ahead economically because they were able to get to Texas? I discussed how difficult it is to answer that question given the fragmentary nature of the financial record.

But Padraig Riley and others suggested that in thinking about how the slaveholding class managed to persevere and reconstitute itself, I should expand beyond thinking about their economic standing to considering how refugeeing might have enabled new forms of political power—focus on political economy, not just economy. They may have left heavily in debt, but debt can be a form of power: it shows the ability to et lines of credit. And whereas I had been thinking about the social networks that facilitated migration as means of profiting economically, as important could be the ways that connections made on the road enabled people to accrue social and political capital that could be useful after the war.16

If there’s anything the existing scholarship on the Civil War and Reconstruction has shown us, it’s that struggles over labor took place on a political terrain—slavery was destroyed by policy (oakes2013) and the slavery-like practices of early Reconstruction and Redemption were resurrected by policy.17 Did refugeeing provide a rehearsal for postwar policies and the use of political power? (One audience member threw out the phrase that I have been using in my Project Description—“Confederate Rehearsal for Reconstruction”—so that was an unexpected confirmation that this may be a useful framing device, perhaps recast per Jim’s recommendation as a “rehearsal for Redemption.”)

I like this reframing too. It would make sense of the fact that my interest has been drawn to Salt Works, Texas Iron Works, the state penitentiary (see walker1988 stuff on A. J. Ward, which everyone was really interested in), contracts between refugees and the government, and so on.

Most of the enterprises of the state government or bodies like the Texas Military Board have been seen by works like kerby1972 and ramsdell1924 as signs of the Confederacy’s internal weakness or the state’s incompetence. But if seen as rehearsals instead of as the final performances, they might gain new relevance as cases where the planter class was working out new ways to use the state in their own interests—cases they potentially learned from in the immediate postwar years. This would make Redemption not just a reaction to Radical Reconstruction but a set of policies with roots in the war years themselves. And it would enable me to sidestep (or bracket) the question of whether the contracts that refugees secured with the government paid off for them personally in dollars and cents, and instead ask questions about policies, political recipes, and institutional change.

All of this could shift my focus away from refugeeing alone towards a general story about what was going on “behind the lines” in the Trans-Mississippi department, with a constant eye on how the continued functioning of slavery in Texas and parts of western Louisiana contributed to the story. Or it could still focus on refugees but pay a lot more attention to their postwar political careers. Either one would probably require me to go back to some of the things I’ve already looked through (like Texas Military Board papers) or the postwar papers of the Weeks Family and the Martin-Littlejohn-Pugh Family. But I also think it would make better sense of what I already have.18

Also got some good pointers towards work I need to consult:

- work of Caroline Shaw on the term “refugee” and its evolution.

- Cherokee slaveholders who were refugeeing or selling slaves in Texas after leaving Indian Terrority—need to follow up with Rachel on this.

Still digesting all the good comments: the discussion was just what I needed to see what I’m finding in some fresh lights!

For more such evidence about refugeed slaves to Texas, see sutherland1980, massey1964, baum2008, campbell1989 and litwack1979.↩

See @berlin1985; @hahn2003; @hahnetal2008; @oakes2013.↩

Judging from the videos, this was a prominent theme at the 2011 Gilder Lehrman Conference entitled “Beyond Freedom,” and also appears in Crystal Feimster’s work, according to people who told me about her 2012 SAWH lecture.↩

Marshall Texas Republican, October 7, 1864; April 17, 1866.↩

hahnetal2008, 72-73, 77 (first quote); berlin1985, 35, 675-676 (second quote); sternhell2012, 7 (third quote).↩

See glymph2008; sternhell2012, 98-100, on this point.↩

These numbers are taken from Cherokee County (TX) Tax Rolls for 1864.↩

Not sure whether I’ll have time to go into it here, but I do think historians need to do more to follow up on Thavolia Glymph’s call to better understand those enslaved people who at least acted as though they wished to stay with planters’ families on the move: “The decision of a slave to stand side by side [or in this case move west] with an owner during the war or to stay put after the war, it would seem, had little to do with the concept of loyalty as it is typically understood in our everyday usage. Its complexities and ambiguities of meaning to those who fought or lived through the Civil War must be teased out” (glymph2008, p. 104).↩

For more on him, see follett2005.↩

William F. Weeks to Mary Weeks, October 31, 1864, Weeks Family Papers, Records of Ante-Bellum Southern Plantations, Series I, Part 6, Reel 18, Frames 656-657.↩

William F. Weeks to John C. Moore, October 31, 1864, Weeks Family Papers, Records of Ante-Bellum Southern Plantations, Series I, Part 6, Reel 18, Frames 654-655.↩

This doesn’t mean economic capital is unimportant. Being able to control even marginal economic resources and capital is important if it allowed the elite planter class to survive and reconstitute itself after the war. The important point here is that I may not have to show that economic activities in Texas brought huge returns for refugees in order to show those economic activities were significant.↩

As I thought about this I remembered a comment made by one of the Pugh’s to Robert Campbell Martin, Sr. circa June 1865: Martin’s friend William W. Pugh, meanwhile, urged Martin to return to Louisiana and remained optimistic that even with “slavery as an institution” destroyed, “the management of ‘free labor’ will probably be controlled by State legislation and in the end if we can procure a sufficiency may be a good substitution for the late institution provided we can control the labor so as to get a quid pro quo for our investment.”↩

Shifting to a political-economic “rehearsal for Redemption” story would mean moving away somewhat from the social history questions I’ve been pursuing about the experiences of people on the ground, and I did get some good questions about those things too—questions about mortality of refugees and refugeed, the means by which planter women controlled enslaved people, slave prices in late-war Texas, and so on.↩